Where’s the Money Coming From, Elon?

Where’s the Money Coming From, Elon?

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Not long ago, a brash entrepreneur whose once-beloved consumer brand had fallen on hard times announced a plan to take his company private. Completing the transaction—the purchase of Dell Inc. for $25 billion by Michael Dell and Silver Lake Management LLC—required countless meetings with special committees, activist shareholders, investment banks, management consultants, and at least four law firms. There were competing offers to consider, and a lawsuit from Carl Icahn to contend with. It took Dell six months just to announce the deal and another nine to close it in 2013.

On Aug. 7, Elon Musk, the chief executive officer of Tesla Inc., appeared to pull off the same trick with a single tweet: “Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding Secured.” A buyout of Tesla at that price—almost 25 percent above where the stock was trading—would make the deal worth $82 billion. That’s more, after adjusting for inflation, than the record-setting buyout of RJR Nabisco that closed in 1989.

The audacity of the maneuver raised immediate questions about where Musk would find the money for such a proposal. And was it a proposal? His flippant tone and apparent certainty spawned instant parodies on Twitter. (New York University professor Scott Galloway: “Am considering going to Chipotle. Funding secured.”) It also caused some to speculate that the most audacious leveraged buyout proposal in history might be just a stoner joke.

That’s because normal companies run by CEOs not named Elon Musk generally make big announcements after markets close to avoid violating U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission rules about selective disclosure. If they do have to announce something big—such as, say, a last-minute $82 billion buyout—the normal practice is to halt trading for a few minutes beforehand and an hour after the announcement to give investors time to digest the news. Tesla trading was eventually halted, but only after Musk had done more than an hour’s worth of tweetstorming. After the trading halt, it took another hour for Tesla to post on its blog an email that Musk had sent to employees about his proposal.

The unusual chain of events made it seem as if Musk had essentially done all of this on his own—an idea that wasn’t entirely contradicted by a 57-word statement, released the following day by six of the company’s nine directors, which contended that discussions on the possible buyout had started only a week earlier. The statement was so carefully worded that it was unclear whether there had been in-depth discussions or if Musk had simply mentioned it a few times before being moved to tweet. The board didn’t indicate who would provide the funding, only saying that funding had been “addressed.” The board, which has been criticized by shareholder rights activists for being largely composed of people close to Musk, including his brother, Kimbal (not among those who signed the statement), also didn’t mention whether a special committee had been formed to consider the proposal.

To buy Tesla at the proposed valuation, Musk, who owns about 20 percent of the shares, would need to come up with $66 billion—a daunting sum even for someone with the auto chief’s capacity for virtuosic self-promotion. The company already has $10 billion in debt, and because Musk has promised to make huge investments in the coming years to build a factory in China, develop a compact SUV, and roll out a commercial semitruck, the automaker will require billions more. Tesla’s credit was downgraded by Moody’s Corp. earlier this year, and Musk has spent the past few months aggressively cutting costs to avoid having to raise additional funds in 2018. Now he’ll have to come up with tens of billions of dollars even before the company has proven it can consistently manufacture its less expensive Model 3 sedan at production rates high enough to make the car profitable.

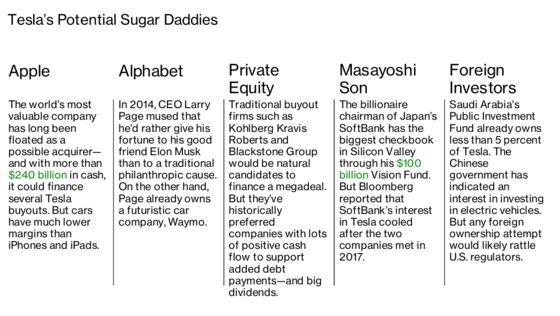

The universe of possible funders is small. Tesla is unprofitable, making it hard to see why traditional leveraged buyout investors—who pay off buyout debt with the cash flow of companies they take private—would be interested in backing a deal. No bank or investment fund so far has indicated it was aware of Musk’s plan. That leaves a handful of large tech companies—Apple, Google, and SoftBank—and sovereign wealth funds as possible candidates. On Aug. 8, Bloomberg News reported that Musk had met in 2017 with Masayoshi Son, CEO of SoftBank Group Corp., about a potential deal, which didn’t materialize. Another candidate: Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, which holds a stake in the automaker that’s less than 5 percent.

Tesla has lots of committed fans, many of whom have put down $1,000 deposits for the company’s Model 3 sedan, in effect giving Tesla hundreds of millions of dollars in interest-free loans. It also has a devoted base of small investors who might be willing to stick with Musk if he takes the company private. That would be very complicated under SEC rules. Still, Tesla fanboys are all in: Galileo Russell, a Tesla investor with a popular YouTube channel, tweeted that he wouldn’t sell a single share at $420 and “wants to be a shareholder for decades to come.”

By the end of trading on Aug. 8, Tesla’s stock was priced at around $370, about 8 percent above the opening price on the day of the tweet. That suggested investors weren’t convinced he could pull off the buyout. Musk has been more optimistic, reiterating that support from investors was “confirmed.” Tesla’s largest shareholders in addition to Musk, including mutual fund companies T. Rowe Price Group Inc. and Fidelity Investments and money management firm Baillie Gifford, have all declined to comment.

In his email to employees, Musk suggested that going private would be good for Tesla because it would insulate the company from the critical news reports and short sellers betting against the stock. Musk has at times seemed to take these critiques personally, lashing out at short sellers on Twitter and snapping on a quarterly earnings call in May, when an analyst asked what Musk called “boring, bonehead questions” about Tesla’s cash position.

“Being public,” he wrote in the email to employees, “subjects us to the quarterly earnings cycle that puts enormous pressure on Tesla to make decisions that may be right for a given quarter, but not necessarily right for the long-term.”

Musk still needs investors’ cash, however. So he appears eager to persuade Tesla’s big institutional holders to exchange their publicly traded shares for stock in a private Tesla—meaning he wouldn’t need to pay them anything right away. That would allow him to buy out the remaining public investors for substantially less than $66 billion. Such a maneuver would leave Tesla looking a bit like Uber Technologies Inc. or Musk’s private rocket company, Space Exploration Technologies Corp., both of which have similar shareholder setups. The short sellers, meanwhile, would have to cover their positions at a huge loss, creating, as Musk has previously threatened, “the short burn of the century.”

Musk’s hope is that investors will look beyond the controversies of the past six months and focus on Tesla’s potential to remake the automotive and energy industries. “Hope all shareholders remain,” he tweeted on Aug. 7. “Will be way smoother & less disruptive as a private company.” Of course, with Musk, smoothness is relative.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.