Generation Lockdown: Where Youth Unemployment Has Surged

Generation Lockdown: Where Youth Unemployment Has Surged

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Carefully laid career paths that suddenly become dead ends, college degrees that no longer open doors, coveted overseas jobs gone in an instant. Whenever the acute phase of the pandemic eventually fades, the crisis will be far from over for young workers in emerging economies.

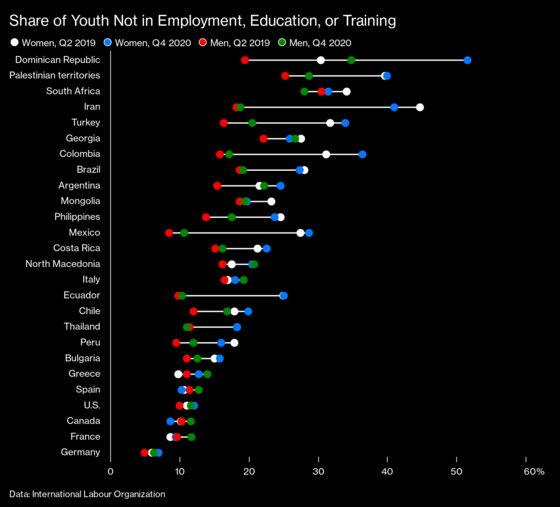

Worldwide, youth employment fell by 8.7% in 2020, vs. a 3.7% drop for adults, according a report the International Labour Organization published in June. Although labor markets continue to rebound in line with the global recovery, ILO’s researchers noted that unemployment data compiled by governments offer only a partial picture of the problems. Their report highlights a different metric, the share of young people not in employment, education, or training—the so-called NEET rate—which has yet to return to pre-crisis levels in most countries.

Niall O’Higgins, one of the authors of the ILO report, warns of the consequences of being shut out of the labor market for an extended time. “Clearly there is a serious danger that young people being out of work for a long period is likely to damage both the individual’s earnings prospects and the society’s productivity and long-term earnings potential.”

The damaging effects go beyond economics. In countries with relatively young populations, having a large number of out-of-work youth can contribute to criminality and political instability.

Warnings of lost generations aren’t new, though. A lot of ground was made up—eventually—in the years after the global financial crisis. Optimists argue that those under 30 are in prime position to learn new skills. Innovative technologies and the gig economy offer opportunities their predecessors didn’t have. And accelerating the pace of vaccination will lead to borders reopening, allowing some young people to seek opportunities abroad.

Still, the challenge will be to create enough jobs for all those joining the workforce. Even before the pandemic, the United Nations estimated the world would need to mint 600 million jobs over the next 15 years to meet youth-employment needs.

Governments are going to have to get creative, says Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Romer, maybe even designing big employment programs aimed specifically at young people. “Having people out of employment is much more costly than we realize. It’s not just the income they would receive or the things they make on the factory line that we lose,” he says. “We lose the process of skill acquisition that goes with being on the job.”

Read on for the stories of six young people who will tell you about the obstacles Covid-19 has laid in their paths. — Enda Curran

Trisha Nicole Miayo, Age 23

Philippines: 18% youth unemployment

Trisha Nicole Miayo, from Laguna province in the Philippines, says she felt fortunate to land a job in the U.S. right after graduating from college in 2019 with a degree in hospitality management and culinary arts. Working as a line cook for a hotel in Savannah, Ga., she made as much as $1,600 a month—more than five times the typical pay for a similar position back home.

Less than a year into her new job, Miayo was laid off when Savannah declared a state of emergency in response to the coronavirus in March 2020. Because she was a contract worker, she wasn’t eligible for severance or unemployment benefits. “I can’t explain the fear,” she says. “I was in a new country, I had to pay my rent and my bills, and suddenly I had no work.”

Miayo looked for employment at other hotels and restaurants, but there were no jobs. She would have accepted a position at a convenience store or caring for children, but she struck out there as well. “My father warned me against going home,” she says. “He said I was better off if I could stay in the U.S., but I just didn’t have enough savings to wait for a new job.”

After returning to the Philippines in April 2020, Miayo tried to set up her own online business selling secondhand clothes (including her own) and other items, but it didn’t take off. Finding a job where she could make use of her degree has been impossible.

The youth unemployment rate in the Philippines eased to 18% in September, from a pandemic high of 32% in April 2020, but it remains almost double the national jobless rate. Employed young Filipinos also recorded fewer hours of work.

Miayo now runs her sister’s mom and pop shop, earning about 5,000 pesos ($100) a month—just enough to pay for her groceries, she says. Now that the United Arab Emirates has reopened its borders, she wants to use what’s left of her savings to go to Dubai to look for employment. If that doesn’t pan out, she knows she might have to put her dream of working in a professional kitchen on hold and consider what’s available—most likely a job at a call center. “By 2022 it will be nearly two years since I’ve had work,” she says. “Sometimes I feel a bit worthless.” —Claire Jiao

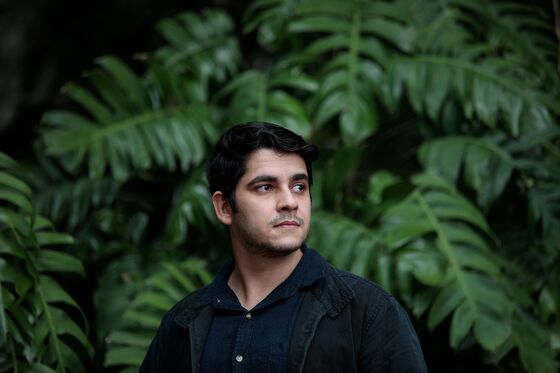

Paulo Henrique Furlan, Age 27

Brazil: 3.5 million college-educated Brazilians are underemployed

In Brazil the Covid crisis has been especially hard on young people who’ve already poured time and money into higher education, only to discover that the opportunities they expected to find after graduation have thinned out or disappeared. The number of underemployed Brazilians with college degrees jumped from 2.5 million in 2019 to 3.5 million last year, an increase of 43%. Among the general population, the pandemic caused an increase in underemployment of 23%.

Paulo Henrique Furlan had always dreamed of becoming a scientist. He earned a bachelor’s degree in biology from São Paulo State University, then spent two years in an exchange program at the Sorbonne in Paris. After sending out dozens of résumés, he landed a job in 2019 at a midsize Brazilian company that farms tilapia. Furlan endured the low pay and long hours because he’d been told the administrative position was a stepping stone to a more senior job that would allow him to apply his knowledge. That didn’t materialize, so last year he quit to pursue a postgraduate degree in geospatial processing and simultaneously a master’s in plant chemistry, with a focus on Brazilian flora.

In October the Brazilian government announced a National Green Growth Program that would ostensibly bring the country closer to its net-zero carbon emissions pledge by promoting green jobs. Still, Furlan, who currently resides in Campinas, about 60 miles north of São Paulo, is far from confident he’ll be able to find work once he’s completed his studies. “In Brazil employers demand experience in an area, but there aren’t any opportunities to gain this experience,” he says.

Indeed, the green jobs push is at odds with some of the other policies of President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration. The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, the main source of public funding for scientific research, had its 2020 budget cut by 87%. Consequently, it had to drastically reduce the amount of money available for scholarships. Government grants for humanities students, set at $272 per month for those in master’s programs and $398 for doctoral students, don’t cover the full cost of tuition at national universities. As a result, Brazil now has an untold number of advanced degree students and graduates driving Ubers and doing other off-the-books gig work. Similarly, Science Without Borders, a government program that’s ushered 100,000 Brazilians into universities abroad, has been almost completely gutted.

The situation threatens to accelerate brain drain. Data compiled by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development shows that 40% of Brazilians living in OECD countries are highly educated, meaning they have received vocational or academic training. Says Furlan: “The incentives to stay here only lessen, and the sensation of impotence in being a researcher in Brazil only grows.” —Shannon Sims

Michael Asare, Age 25

Ghana: 50%-plus youth underemployment

Michael Asare blinks away tears as he recounts how Covid snatched away his job waiting tables at a Chinese restaurant in Ghana’s capital of Accra. He’d started right out of high school, gradually working his way up to 700 cedis ($115) a month in pay. Then came the coronavirus. “We were paid half salary for two months, but on the third month our manager said the restaurant was not making anything to even manage the half salaries, and so he gave us letters and added two months full salaries as our severance packages,” he says.

Ghana suffered high rates of youth unemployment even before the pandemic, because the commodity industries that have powered its economy in recent decades—gold, cocoa, and, more recently, oil—are not big job generators. According to a World Bank report from last year, youth underemployment in the country exceeds 50%, which is higher than in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa. (Government data is spotty and out of date.)

With bills piling up for food and other essentials for his 7-year-old daughter and his father, who’s been undergoing treatment for prostate cancer, Asare had no choice but to dip into the 2,500 cedis he’d put aside so he could study for a business degree. In August he began working as a waiter at a Thai restaurant, and he’s now concentrating on rebuilding his finances. “I live within my means and save as much as possible,” he says. — Ekow Dontoh

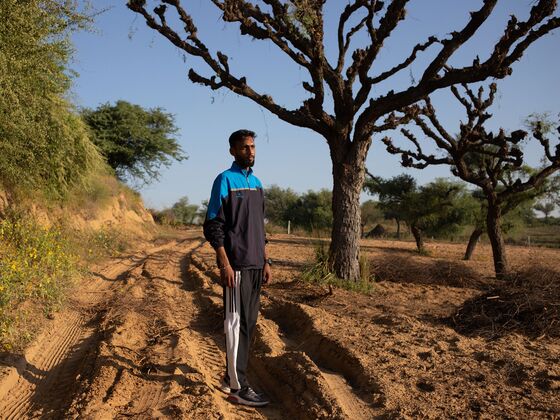

Hemant Singh, Age 21

India: 39% youth unemployment

Hemant Singh is one of many Indian youths whose career aspirations have been upended by the pandemic. Two years ago he parlayed a stint playing basketball for Delhi’s state team into a job as an assistant sports teacher at an international school there. The position paid 10,000 rupees ($135) a month, and Singh hoped it would set him on a path to becoming a professional basketball coach.

Then the coronavirus hit, forcing schools and other educational institutions in big cities to shut down. Singh and the relatives he’d been living with had no choice but to return to their home village in the northern state of Rajasthan. For the past seven months, Singh has been tending a small liquor store his family owns. The shop is open from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. daily, but the young man also spends nights there to ensure there are no break-ins. He steps out only in the morning, to bathe and eat, and at dinnertime. “I never thought that I would lose my job from Covid, and now I don’t see myself playing basketball anymore,” he says.

India’s working-age population grows by about a million a month, but less than 10% secure jobs in the formal economy. Although economic growth has rebounded from the depths of the crisis, unemployment among 20- to 24-year-olds was almost 39% as of March, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt. Ltd.

Singh has a new five-year plan: He says he hopes to save enough money to study for a bachelor’s degree in physical education, so he can apply for jobs back in the capital. “I dream of becoming a government sports teacher, if I am able to clear their exam,” he says. “I don’t know anything other than sports or teaching sports.” —Jaiveer Shekhawat and Vrishti Beniwal

Sun Xiaowen, Age 23

China: 15% youth unemployment

China charted a V-shaped rebound from the initial hit of the pandemic, but its economy has slowed markedly this year. As a result many young people are finding it difficult to get a foothold in the labor market.

One of them is Sun Xiaowen. Having graduated from the prestigious Renmin University of China in 2020, the Shanghai resident had been planning to head to Germany to continue her studies after taking a gap year. With the coronavirus still complicating travel, she changed tack. In April of this year she took a job at an agency that helps young Chinese applying to study abroad.

“Graduates from the class of 2020 have been affected by the epidemic,” Sun says. “The employment situation of my former classmates and friends isn’t as good as expected. We have to compete not only with students graduating in 2021 but also those who got laid off because of the pandemic.”

China will graduate 9.1 million university students in 2021, surpassing last year’s record of 8.7 million, according to official figures. Unfortunately for all these new grads, many Chinese businesses have scaled back hiring. Last year only 11.9 million new urban jobs were created, down from 13.5 million in 2019.

Youth unemployment peaked at 16.8% in July 2020, and though it had fallen back to 14.6% as of September 2021, the divergence between the youth and adult rates was 3 percentage points wider than it was at the end of 2019.

To address the issue, China’s central government is pushing a plan that includes helping younger workers start their own businesses, strengthening vocational training, and making factory jobs more appealing.

Sun says she worries that her position at the study abroad agency may be at risk from a government crackdown on private tutoring services, but she’s resigned about the situation she and many of her peers face. “The job market is filled with highly educated job seekers,” she says. “You’ll need to spend a lot of time researching potential employers and improving your skills to find a genuinely ‘suitable’ job. It is what it is.” —Lin Zhu, with Bihan Chen

Fikile Lucie Moni, Age 24

South Africa: 64% youth unemployment

Fikile Lucie Moni dropped out of an engineering course in 2017 because she couldn’t afford the fees. She’s barely been employed since, except for a few short-term contracts. Nowadays she works just two hours a week, helping a small traditional beermaker with its computer records.

In the dusty townships that stretch north for miles from Pretoria, South Africa’s capital, Moni’s story isn’t unusual. Even prior to the pandemic, 58% of those age 18 to 24 nationwide were unemployed, with many turning to illegal drugs, alcohol, or crime to dull the boredom of a life without opportunities. Under a more expansive government measure of unemployment that takes into account those who’ve given up looking for work, almost 4 out of every 5 in the age cohort are jobless. That’s partly because of Covid-19, but the bigger—and chronic—problems are a dysfunctional education system and a stagnant economy.

“It’s devastating to not know where your next meal is coming from,” Moni says, sitting in a sparsely decorated room at the Katekani Community Project, a nonprofit based in a single-story building in Mabopane, a township 24 miles north of the capital. At the organization’s weeklong life-skills course, Moni learned how to compile a résumé and conduct herself during job interviews. She also completed a three-week course in computer basics. “I learned how to express myself as a person,” says the soft-spoken young woman, who hopes to get a position in business administration. “I learned how to operate a laptop.”

Despite that training, Moni hasn’t been able to find a full-time job. In Mabopane and nearby townships, there are few amenities and even fewer opportunities. Printing curriculum vitae and taking a minibus taxi to Rosslyn, an industrial area 9 miles away, costs money that out-of-work young people don’t have. Many don’t even have the identity documents they need to apply for work. “We are trying, but we are not winning,” says Tebatso Mphila, who runs one of Katekani’s two branches.

At the Refentse Health Care Project in Stinkwater, a township 11 miles northeast of Mabopane, young people learn how to answer phones just in case a job comes up at a call center. On a nearby street, youths march up and down as part of their training to become security guards. Originally set up in 2000 to help provide home care for the growing number of AIDS sufferers in the community, the project expanded into job training in 2012. “The bigger challenge that we had was the orphans, those who had lost their parents to HIV and tuberculosis,” says Phillip Mailwane, who runs the Refentse center. “We had to care for these young people and change their livelihoods.”

Mailwane spends much of his day approaching companies to try to line up jobs for the students at his center. The odds are stacked against them, he says. Of the 30 or so 18- to 35-year-olds who enroll for the three courses at Refentse every quarter, perhaps five find work. “It’s getting worse, because there is nothing,” says Lizzie Mpheteng, 26, who volunteers at the center because she hasn’t found work and finds it mind-numbing to stay at home all day. “A lot of the youth are not working or schooling. They just drink, drink, drink.” — Antony Sguazzin

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.