When the Stock Market Goes Mad, Look for Real Value

When the Stock Market Goes Mad, Look for Real Value

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- This may be the least informative earnings season in history. Companies’ first-quarter financial results are scarcely relevant because they cover a period that mostly predated the pandemic. About a fifth of S&P 500 companies have stopped guiding Wall Street analysts about how much they expect to earn this year. Wild swings in the market give the impression that stock prices have become unanchored from reality.

Here’s the surprise, though. The lack of information about the short-term situation may force investors to do what they should have been doing all along, namely focus on companies’ long-term earnings potential. Lazy expedients such as extrapolating the latest results into the future or leaning on the forecasts of the chief financial officer aren’t working right now. Stock prices are being influenced instead by meaningful considerations: Is there a future for cruise ships? Will we need less office space because we’re staying home, or more because we’ll sit farther apart? Will distancing create more demand for cars and less for airlines?

These are bigger questions than the ones that accompany an ordinary business cycle fluctuation. “Investors have never had to make a decision like this before”—about which businesses will survive—says David Russell, vice president for market intelligence at TradeStation, an online brokerage.

Aswath Damodaran, a valuation expert at New York University’s Stern School of Business who began blogging at the start of the last financial crisis, is impressed by how investors have handled themselves this time. “I know that it is fashionable to talk about how inefficient and volatile markets are but this crisis, in many ways, has been surprisingly orderly and markets have dispensed punishment judiciously, for the most part,” he wrote in an April 24 post.

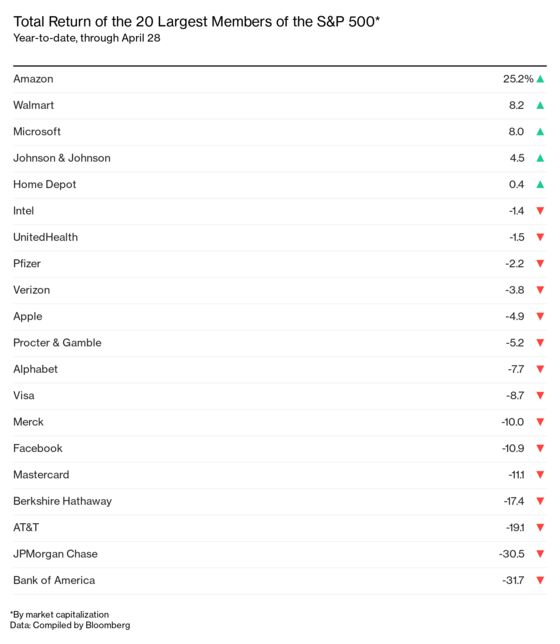

There was plenty of craziness in stocks from their February peak to their March trough. Good companies were pulled down along with bad ones. Since then, though, investors have tried to winnow the wheat from the chaff. Amazon.com Inc., which lost nearly a quarter of its value in the selling wave, has since risen 38% and touched a record. Health-care giant Johnson & Johnson is up 36% from its recent low. Meanwhile, big banks such as Citigroup Inc. are not far above their cyclical bottoms, reflecting ongoing concern about loan losses. “It might take a day, a week, or three weeks, but eventually the market mechanism separates good from bad,” says Dubravko Lakos-Bujas, chief U.S. equity strategist and global head of quantitative research at JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Looking well past the current year’s earnings is something investors should do always, not just when there’s a pandemic going. Quarterly earnings guidance is at best a crutch. “If you want to get an investment edge, company guidance doesn’t buy you anything,” says Erika Karp, founder and chief executive officer of Cornerstone Capital Group.

That’s where long-term analysis comes in. Most of the value of a growing company “comes from the aggregate cash it will generate in the years 2023-2050 and beyond,” Win Murray, research director at fund manager Harris Associates, wrote in a February newsletter. Hypothetically, he wrote, if 2020 cash flows fell to zero but later years were somehow unaffected, a company’s market value “should only fall by 4%-5%.”

Investors are focusing less than usual this quarter on which companies beat and which companies fell short of earnings expectations, says Savita Subramanian, an equity and quant strategist at Bank of America Securities. The way the game is ordinarily played, company executives steer analysts toward an earnings-per-share number that they’re confident they’ll be able to beat, so surpassing expectations is in fact expected. This quarter, the day-after stock-market underperformance by companies that fall short of expectations is only one-third the normal amount, she calculates.

That tolerant reaction is a good sign. “There’s a growing disillusionment” with management of earnings expectations, Subramanian says. “People realize it’s a game.” It’s a game with pernicious consequences: A survey of financial executives by Duke University published in 2005 found that a majority of them would avoid initiating a project with a positive long-term value “if it meant falling short of the current quarter’s consensus earnings.”

Of course, it’s appropriate to focus intently on the short term if a company is at risk of failing. Bankruptcies are already beginning to spike. But most big, publicly traded companies will survive. “My mantra is: depression-like shock, no depression,” says Joseph Brusuelas, chief economist at RSM Global, an audit, tax, and consulting firm. Those that make it past the pandemic could actually benefit in the long run from a reduction in competition, says Harris Associates’ Murray.

If you spot a company whose stock price looks high in comparison with its projected earnings over the next year, it could be a sign of a bubble—or it could be evidence that investors are looking beyond that 12-month cutoff to better days ahead. —With Claire Ballentine

Read more: Smart CEOs Are Playing Dumb in the Age of Coronavirus

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.