What It Means to Buy Stock in a Bankrupt Company Like Hertz

What It Means to Buy Stock in a Bankrupt Company Like Hertz

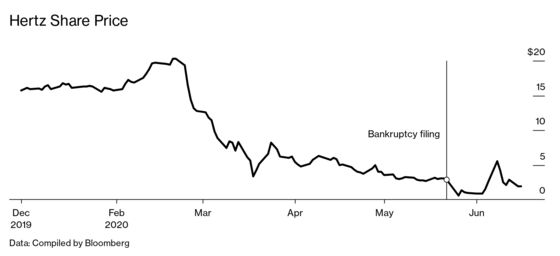

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It’s one of the wildest tales in 2020’s wild-enough market. Rental car giant Hertz Global Holdings Inc. declared bankruptcy, and its stock quickly fell to 56¢ a share. Then hordes of investors—apparently looking for a cheap way to buy the dip—piled into the stock, driving the price up tenfold at one point. That gave Hertz a bright idea: Raise some cash by selling even more shares. A judge approved the sale.

On June 17, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Jay Clayton told CNBC that the agency had “comments” for Hertz on its plan. Hertz suspended the stock sale pending review. Whatever happens, the saga casts light on why buying shares in a company that’s filed for bankruptcy is so risky.

Hertz’s filing to sell its shares came with more dire warnings than a bottle of bleach. While debt holders often get some fraction of their money back, equity investors rarely get anything out a bankrupt company. The filing is clear: “We expect that common stock holders would not receive a recovery through any plan,” unless all debt is paid in full. And that would require a rapid return to travel at levels before the Covid-19 pandemic.

For lots of investors who’ve played Hertz shares, the main idea was probably to hop in and then hop out while the stock was still climbing. “There’s nothing wrong with taking profits,” says Arissa Washington, 23, a film director and photographer in Wisconsin, who picked up shares for 75¢ and sold on June 5 after more than doubling her investment. But ultimately a stock’s worth depends on the underlying value of the business, and companies in Chapter 11 are required to use their assets to first pay their debts before shareholders can lay claim to the leftovers. Often there aren’t any.

Secured lenders—the ones with collateral—go to the front of the line and can dip into the company’s cash and property until they get everything they’re owed. Unsecured creditors, such as bondholders and suppliers, come next. If there’s not enough to pay them back in full, which is usually the case, they might get an equity stake in a reorganized company. But the old shareholders are usually wiped out.

“There’s no value there,” says Joel Levington, credit analyst with Bloomberg Intelligence, speaking of Hertz. Of Hertz’s debt load, $14.4 billion is vehicle debt—meaning its owed to holders of securities that are backed by the value of the rental company’s 494,000 cars. Hertz essentially leases its cars from those bondholders. (Yes, rental car companies rent their cars.) Figuring out what to do with all these cars and the leases on them is a key issue between Hertz and its creditors, and it’s been complicated by the April collapse of the used car market. In a nutshell, the collateral isn’t worth what it used to be.

Some companies find ways to reorganize that allow stockholders to keep something. But such deals can only go forward with creditor consent, says Bruce Grohsgal, a longtime bankruptcy lawyer who’s now a professor at Widener University’s Delaware Law School. For example, bondholders and fire victims cut a deal with shareholders in the reorganization of California utility PG&E Corp. after its equipment was blamed for causing wildfires. The agreement diluted shareholders’ stake, but didn’t leave them with nothing.

There is a scenario in which current Hertz stockholders might retrieve value. If Hertz is able to sell stock—and raises enough—it can use the money for operations, including paying costs to bondholders so the company can keep renting out its fleet of cars. Travel could come back. And arebound in the potential resale value of Hertz’s cars would make it easier to resolve the problems with its vehicle debt.

But while used car prices are recovering a bit, they will still be down this year. Even before the pandemic, General Motors Co. said that it expected prices to fall 4% this year. And travel? Hertz relies heavily on airport traffic, and while the Transportation Security Administration said on its website that mid-June traffic is better, it’s still running at 20% of where it was a year ago.

After hitting a post-Chapter 11 peak of over $5 a share, Hertz was recently trading at about $2. “The stock is not for true investors,” says Bloomberg’s Levington. Rather, it’s a “lottery ticket.” Those don’t usually pay. —With Vildana Hajric

Read next: Pessimistic Pros Missed the Big Rally, and So Did Many Americans

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.