What a 1902 Coal Strike Tells Us About Essential Workers Today

What a 1902 Coal Strike Tells Us About Essential Workers Today

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In the weeks since the coronavirus pandemic took hold in America, the country has come to redefine essential work and to appreciate that essential often means vulnerable. We’ve watched the people who pack online orders, stock grocery stores, and deliver takeout assume unprecedented risk, often for low pay in unsafe working conditions. Some who’ve protested have been silenced; some who’ve carried on have been infected.

We’ve also seen evidence, though, that in a collective (and profit-threatening) emergency, the big companies that employ essential workers will, under duress, raise wages and offer paid sick leave. The government will find the money to give many families at least $1,200, no application necessary. And at seven every night, we cheer.

But will the country remember its newly essential workers once the social and economic shock wears off? That hopeful and haunting question will be on many people’s minds leading up to the presidential election in November, and in the months after. Covid capitalism could see the country extend the privileges of the wealthy, of monopolistic corporations, of the insured, of anyone who’s had the luxury of keeping their jobs while working from home. Or it could see the country finally rewrite its increasingly one-sided social contract.

Reckonings like this tend to come every couple of decades—expected by some, denied by others. On occasion, American capitalism is reformed; rarely does it stay that way. The Great Depression brought on Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, which eventually helped the country return to prosperity, but not for all, which in turn prompted the Great Society reforms of Lyndon Johnson. Before either of those movements, at the start of the 20th century, came Theodore Roosevelt’s Square Deal.

The progressive moment announced itself in 1902 with a monthslong coal strike that revealed miners to be the essential and undervalued workers of their time. Americans had known, in an abstract way, that the advances and luxuries of the industrial age depended on the willingness of a few hundred thousand men to hazard dangerous conditions and high mortality rates for low pay. But then, as now, it took a crisis to crystallize in people’s minds that the country needed an economy that worked for everyone.

By 1900, America’s restless ambitions were being mechanized and manufactured. With automobiles coming onto the streets, and electric lights and telephones being installed in homes, the standard of living was improving. There were more roads and rail lines, more buildings, bigger corporations, bigger cities. But many people also felt confused and uprooted, surrounded by the unfamiliar.

Almost half a million immigrants arrived in 1901, only to find themselves crowded into unhealthy tenements and some of the most difficult and unreliable jobs. The backlash against Reconstruction in the South—and pervasive racism throughout the country—meant many African Americans were struggling to rise out of poverty. Women could work on the production lines and in the sweatshops, but they earned considerably less than men, and few could vote. When Roosevelt came to power in 1901 after the assassination of William McKinley by a former factory worker, the possibility of social unrest seemed close. “The storm is on us,” said Henry Adams, a historian and friend of the new president.

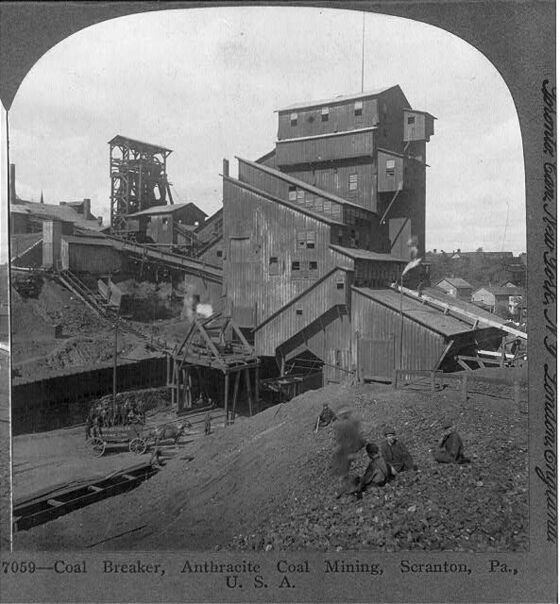

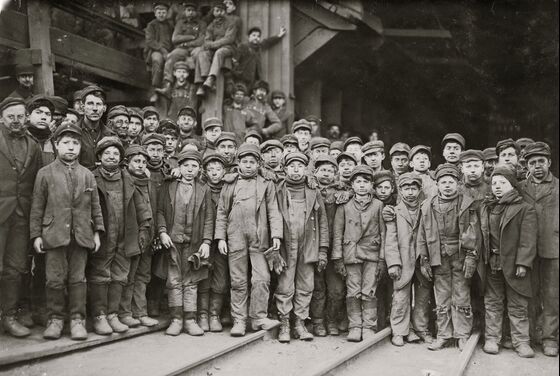

The tempest threatened to begin in the anthracite coal mines of northeastern Pennsylvania. For decades the region’s workers had been doing some of the country’s most dangerous jobs. They knew all the ways they could die. Mines could collapse, rocks could fall, water could rise. The dust and damp and explosive powder could turn their lungs black. They knew the whistle that signaled for work to begin, and the one that signaled someone had met his end. In 1901 the warning whistle blew three or four times a day in the 346 Pennsylvania mines that held almost all of the nation’s hard coal. Twelve hundred men were injured that year, and an additional 500 died. The bodies were claimed by families who might not have set aside money to bury them, and only some employers would help. If a miner died alone and friendless, his corpse was donated to a medical school and dissected.

America’s industrialization depended on that coal. Anthracite made possible stronger grades of iron and steel, which made stronger rails, which allowed for heavier locomotives, which made interstate trade on the transcontinental railroads possible. It generated steam for those locomotives and for manufacturing glass, textiles, ceramics, and chemicals. It warmed the homes, offices, and schools of a distant America, urban and modern.

The coal companies depleted the easily reached deposits in the years after the Civil War, which meant they had to spend more to extract what remained. Independent operators eventually sold out to bigger companies, which were backed by the railroads, which had financial supporters of their own. By 1874 most of the coal land in northeastern Pennsylvania was controlled by the railroads. And by 1900 most of the railroads were controlled by John Pierpont Morgan. Morgan wasn’t the richest person in the U.S., but through his companies and connections he influenced more money than anyone else in the country, maybe the world. If anything important was happening on Wall Street, Morgan was assumed to be behind it.

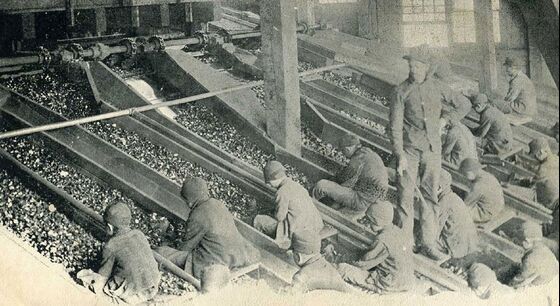

As the coal railroads came under his sway, a cartel took shape. Having beaten back labor unrest and early attempts at unionization, the anthracite bosses frequently hired workers they thought wouldn’t challenge their authority. They recruited miners from central and eastern Europe, often more than they could fully employ, which helped to depress wages. Then they lowered production and raised prices.

But in the Midwest and states such as West Virginia, where coal was bituminous and more mines independently owned, labor organizers had some success. The United Mine Workers, which claimed 93,000 members, was headed by John Mitchell, who’d first gone underground in Illinois at age 12. At 28, he was ambitious, well liked, and politically astute—and he saw an opportunity in Roosevelt. The new president was promising a government that would hold corporations to account, that offered the same justice to the privileged and the neglected. He was young and kinetic, a moralist and an opportunist, with a fighter’s instinct for keeping opponents off-balance and a showman’s sense of drama.

Five months after Roosevelt was sworn in, he took on Morgan and the enormous railroad company he’d just formed, Northern Securities, which threatened to dominate the country’s vast Northwest. The government called on the courts to enforce antitrust law and break up the company. Morgan was shocked by the attack. Wall Street traders described it as a “thunderbolt out of a clear sky”—unreasonable, dangerous, theatrical.

During those early months of 1902, Mitchell, who’d been organizing Pennsylvania’s anthracite miners for two years, hoped to force their employers to the table to discuss wages, working conditions, and union recognition. He asked in February, in March, in April. The response, when there was one, was uncompromising: no, no, no.

On May 12, start whistles pierced the morning. In Coaldale, Carbondale, Shamokin, Panther Creek, and other towns, more than 147,000 men and boys heard the call to work. They ignored it. The miners were aware of what their actions would bring them: payless days, rationed food, untreated illnesses, possibly eviction. “I am of the conviction that this will be the fiercest struggle in which we have yet engaged,” Mitchell wrote to the activist Mother Jones.

At first the coal executives seemed unconcerned. Some were reportedly playing golf early on. “We are confident they will regret their action and be glad to resume work on the old terms,” one executive said. Later, George Baer, president of the most important of the coal railroads, the Philadelphia & Reading, said: “These men don’t suffer. Why, hell, half of them don’t even speak English.”

As the strike stretched into days, then weeks, it revealed itself to be more than a protest for fair wages and treatment, more than a face-off between labor and capital. It was a confrontation between a past in which power was concentrated and a future in which it was shared.

Public sympathy was with the miners; a relief fund swelled with contributions. But Roosevelt was initially unsure of his role. His secretary of labor suggested that the miners be allowed to bargain collectively and have their complaints heard by an impartial panel, and that the companies try a nine-hour workday instead of 10. In exchange, he held, the miners should promise not to intimidate those who didn’t want to join the union. Roosevelt liked the recommendations but had no real power to implement them.

In July violence erupted in Shenandoah. Strikers confronted three men who’d continued to work, police opened fire, and at least 20 miners and five officers were injured. The Pennsylvania National Guard arrived the next day to keep order.

Mitchell and Roosevelt watched anxiously; Mitchell because he was worried the strikers would lose support, Roosevelt because he feared the violence would spread. Three weeks later, though, public opinion turned decisively against the coal barons, when the newspapers got hold of a reply Baer had written to a letter from a concerned citizen pleading with him, as a good Christian, to settle with the miners. “The rights and interests of the laboring man will be protected and cared for,” Baer wrote, “not by the labor agitators, but by the Christian men to whom God in His infinite wisdom has given the control of the property interests of the country.” A God-given right to dominate the nation’s economy? That was too much.

Eastern governors were by then calling on Roosevelt to at least temporarily take over the mines or to prosecute the coal barons for operating a cartel. Encouragement and assistance for the strikers flooded in from other labor unions, charities, religious congregations, political and reform clubs, debating and literary societies. Prominent citizens urged the miners, operators, and federal government to end the conflict. In New York City, 10,000 people rallied on the strikers’ behalf.

Their support wasn’t merely a gesture of solidarity. It was also a recognition of just how much the nation depended on coal. By September, the U.S. Post Office was threatening that, absent heat or light, it would have to shut down. Public schools were warning they might not be able to remain open past Thanksgiving. Steel mill owners in Pennsylvania told their workers to prepare for mass layoffs. In Milwaukee, men stole wooden beer kegs from saloons to burn as fuel.

The New York State Democratic Convention backed a call for the government to take over the mines. Business leaders agreed. “The operators do not seem to understand that the present system of ownership … is on trial,” Roosevelt wrote to a friend. America was facing a winter of darkness, sickness, and starvation. Some might freeze to death; others might riot. The strike could spread. If panic outran reality, the government might have to respond with force. Roosevelt feared the crisis could become almost as serious as the Civil War.

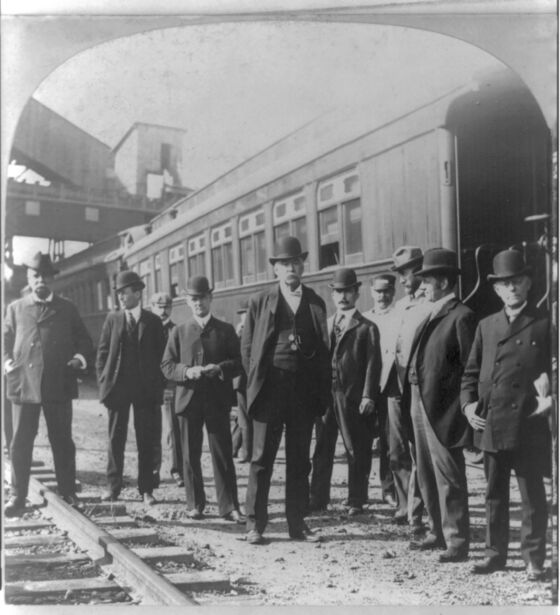

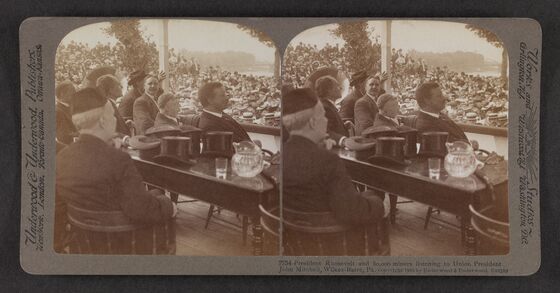

The time had come. On the first of October, he sent a telegram to the owners of the six biggest mines. “I should greatly like to see you on Friday next, October 3rd, at eleven o’clock am, here in Washington, in regard to the failure of the coal supply, which has become a matter of vital concern to the whole nation,” he wrote. “I have sent a similar dispatch to Mr. John Mitchell.” With that, Roosevelt became the first president to mediate between big business and labor, after decades in which the government had sided firmly with the former.

When the men gathered on Oct. 3, Roosevelt appealed to the executives’ patriotism. “Meet the crying needs of the people,” he said. They replied that they wouldn’t meet anything but the miners’ surrender. Mitchell said the miners wouldn’t return to work until their demands had been considered by an independent commission.

“Well, I have tried and failed,” Roosevelt wrote that evening to a Republican senator. He said he was considering “a fairly radical experiment”—sending in the army to take over the mines. Winter was closing in, and all the news was disturbing. A major utility, the Peoples Gas Light & Coke Co. in Chicago, calculated that its coal supply would run out in 20 days, leaving 350,000 businesses and residences in the dark. Brooklyn’s courts were out of coal. On Dundee Island, in New Jersey, a band of 50 men and women stole several tons of coal from parked railroad cars, using nothing but wagons and bags.

Roosevelt had one final move he could make before sending in soldiers: turning to Morgan. The man whose company he was trying to break up was also the only man capable of bringing Baer and the others to heel. By now, even Morgan was embarrassed by their arrogance and intransigence. He feared the public’s hostility toward the coal industry might spread to his other, more profitable companies. Most of all, he, too, was worried about disorder.

Morgan agreed to meet with Elihu Root, Roosevelt’s secretary of war and a former corporate lawyer. Both Morgan and Roosevelt trusted Root far more than they trusted each other. On Saturday, Oct. 11, the financier welcomed the secretary onto his 304-foot yacht, the Corsair, which was anchored in the waters around Manhattan. Root and Morgan conferred for almost five hours, drafting a statement in pencil on eight pages of ivory-colored Corsair stationery.

The document was designed to reflect the coal operators’ point of view, condemning “the reign of terror” in the anthracite fields and recognizing “the urgent public need of coal.” But it ended by proposing the creation of a presidential commission to arbitrate the disputed issues. It was exactly the idea Mitchell had proposed, Roosevelt had supported, and the executives had rejected.

The miners agreed and got back to work. Headlines called Roosevelt a statesman, describing his mediation as a welcome approach and his commission as impartial and expert. “I feel like throwing up my hands and going to the circus,” he wrote.

When the commission met a month later, the men of coal country spent days testifying to injuries they’d never been compensated for, hours they couldn’t count on, wages never paid in cash. They spoke of debt and of death. One, Henry Coll, summed up 29 years underground: leg and fingers broken, ribs smashed, skull fractured, half-blind. “I lost my right eye, and I can’t see out of the glass one much,” he said. He’d been evicted and forced to move into a house in such poor condition that his kids had gotten sick. His wife, already ill, died soon after. “She died?” the head of the commission repeated. She died.

When it was Baer’s turn to speak, he described mining—the deep underground, explosive work of it—as an unskilled trade that more men than necessary wished to undertake. “What does that indicate? Why, that labor there is attractive,” he said. Asked to comment on the inequalities between the prosperous and the poor, he replied that they existed “to teach the power of human endurance and the nobility of a life of struggle.”

The commission ultimately agreed to cut the miners’ workday to nine hours and award them a retroactive 10% wage increase despite the likelihood of a 10% increase in coal prices. Mitchell’s union didn’t win recognition, but the commission did say that all workers had the right to join one. It also created a permanent board to rule on future disputes.

Both sides declared victory. Mitchell said he was pleased to win a wage increase. The coal presidents said they were gratified Mitchell didn’t get union recognition. Roosevelt said the commissioners had done a great job and invited them to dinner at the White House. Morgan said nothing.

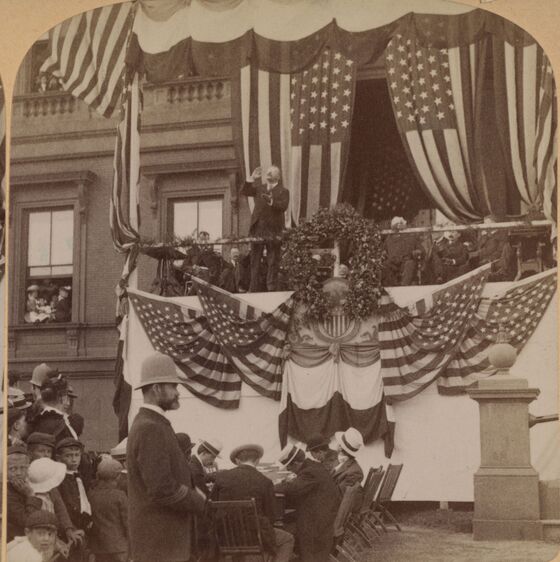

The president came away from the episode emboldened to push for a progressive agenda. “I stand for the square deal,” he said. “But when I say that I am for the square deal, I mean not merely that I stand for fair play under the present rules of the game, but that I stand for having those rules changed so as to work for a more substantial equality of opportunity.”

In March 1904, the government won its antitrust case against Morgan’s railroad company. It was the first time such a powerful businessman had been held accountable to the public rather than just to the bottom line or investors. Coming eight months before the presidential election, the decision helped Roosevelt win in a landslide. In his second term, he pressed Congress to pass stricter railroad regulations and create an agency to ensure food and drug safety. He supported unions, eight-hour work days, and an inheritance tax. America, he said, must not be “the civilization of a mere plutocracy, a banking-house, Wall-Street-syndicate civilization.” Making change could be dangerous, he said, but doing nothing could be fatal.

The U.S. was on its way to becoming a richer and more powerful nation, but it was newly aware that prosperity for some meant anxiety for others. Even those enjoying their perch in the middle class were uneasy as they realized their dependence on left-behind, sometimes-displaced, often minority workers. Then, as now, energy and anger were building.

Roosevelt grabbed these forces and tamed them. The coal strike and antitrust fight gave him momentum. Labor activists and government reformers, populists, and socialists pushed him to stand up for the working class. His changes seemed too timid to some, too radical to others, including some in his own party. But they set a precedent for a more progressive society and a moral tone that soothed an agitated nation.

Today’s labor activists and union leaders hold less sway; with the advent of the gig economy, work has become even more provisional and fragmented. Joe Biden just beat Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren in the Democratic primary. Yet ideas that were once unfeasible are now up for discussion: universal health care and child care, a living wage, paid sick leave and parental leave. Calls to renegotiate the social contract have gotten louder, and polls suggest that more people are listening. Essential workers at some of the country’s biggest companies plan to strike on May 1 for more protection and compensation. There will be an election; there could be a new president.

Someday it will be quiet again at seven. What will America do then?

Adapted from The Hour of Fate: Theodore Roosevelt, J.P. Morgan, and the Battle to Transform American Capitalism.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.