What Going Private Under Patrick Drahi Might Mean for Sotheby’s

What Going Private Under Patrick Drahi Might Mean for Sotheby’s

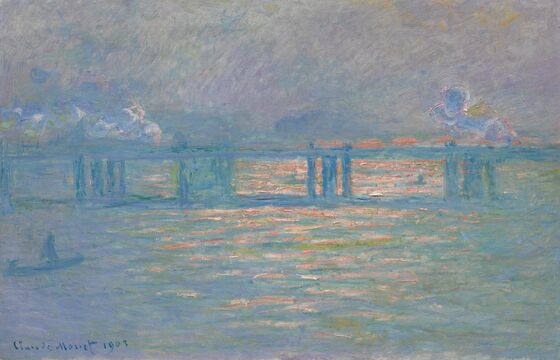

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On Sept. 5 shareholders of publicly traded Sotheby’s approved a $3.7 billion acquisition offer from French telecommunications tycoon Patrick Drahi. Come this November during the auctions in New York, clients bidding on treasures like Claude Monet’s Charing Cross Bridge will likely be raising their paddles inside the halls of a private company.

While the news sent shock waves through the art world, Drahi, not known as a major collector, declined to speak publicly.

Art lore says that the public Sotheby’s was long at a disadvantage to the more nimble and risk-tolerant Christie’s, which is owned by French billionaire François Pinault. Christie’s doesn’t have to answer to shareholders and isn’t punished by stock declines. There’s also the presumption that Pinault’s deep pockets allow it to offer far higher guarantees—which effectively ensure that the consignors will be paid a certain amount, giving the house another leg up.

But even as Sotheby’s evolves, clients of the 275-year-old auction house—collectors and dealers who buy and sell Picassos and Warhols, Chinese porcelain and $437,500 Nike sneakers—predict business as usual.

“Sotheby’s going private, I don’t see that it would have that much of an impact on most people,” says Morgan Long, senior director at the Fine Art Group Ltd., a regular client. “I don’t find on the consignment side or the buy side that there’s much difference between Sotheby’s and Christie’s.”

“There was always this perception that being public hampered our ability to do business,” says Scott Nussbaum, who left Sotheby’s in 2015 after 13 years to join Phillips, a boutique auction house owned by Russia’s Mercury Group. “Now that I work for a private company, I am not sure that’s true.”

Nonetheless, Sotheby’s going private is important for the art market, where it and Christie’s accounted for 46% of $29 billion in global auction sales in 2018, according to a UBS report. Clients are watching to see if Sotheby’s will attract more rainmakers and reduce its red tape.

“It’s bullish for the market,” says collector and dealer Adam Lindemann. “People from the outside will take the art market forward. It can’t be just musical chairs between [gallery owners] Larry Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth, and David Zwirner.”

Sellers make choices between houses, in part, based on which team can maximize the value of an object and offer better financial terms, says art adviser Gabriela Palmieri, a former Sotheby’s specialist. For buyers, the house they choose hinges on the quality of artworks—and such practicalities as more favorable payment plans and efficient shipping.

Emotions also play a role in whether a client chooses Sotheby’s or Christie’s or Phillips. Long, of the Fine Art Group, says one of her clients only works with Christie’s because his father had a long-term professional relationship with a specialist there. That doesn’t change with corporate ownership.

Then there’s the optics, which, given that the art world is built on perception, is no small thing. “For many years we thought that Christie’s was doing better than Sotheby’s, but we didn’t really know,” says Barbara Bertozzi Castelli, owner of Castelli Gallery in New York. “Maybe they were losing money.”

Pinault understands and accepts the risks and rewards of owning Christie’s, says Paul Gray, who’s bought works on behalf of clients including hedge fund manager Ken Griffin. “That definitely gives them an edge in guaranteeing works at speculatively high levels,” he says. “We’ve seen this strength come back to haunt them, and the house has ended up with some really major buy-ins of guaranteed material with writedown sales afterwards.” That is, if a work fails to sell, Christie’s (or Pinault) has to purchase it at the guaranteed price.

Sotheby’s, until now, was a different story. Losing money on a guaranteed artwork, which would have to be disclosed, often contributed to disappointing quarterly results. Shares would nosedive, which in turn could make management more reluctant to offer lucrative deals to future sellers of the most prized works. This dynamic will now change, but as a result the functions of a huge chunk of the market will be hidden from view.

Drahi, who’s worth $10.7 billion, hasn’t disclosed his vision for Sotheby’s. His 2016 acquisition of Cablevision from the billionaire Dolan family was followed by cost-cutting of jobs and programming, according to a lawsuit filed last year by the Dolans against Drahi’s telecommunications giant, Altice Europe NV. The parties settled in August.

Whatever lies in store for Sotheby’s, Drahi isn’t spending the money “to leave it as it is,” says Alberto Mugrabi, whose family is among the most ubiquitous buyers and sellers at auction. Technology is expected to be part of the new management’s focus given Drahi’s role as president of Altice. “He has new ways of seeing things,” Mugrabi says. “The new owners will give me more options how to sell my art.”

Come November, whatever the outcome for the Monet, estimated at $20 million to $30 million, employees won’t have to worry about satisfying shareholders. “They would need to report to one person, and one person only,” Long says.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Chris Rovzar at crovzar@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.