What Colorado’s Public Health Insurance Push Means for Democrats

What Colorado’s Public Health Insurance Push Means for Democrats

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For Democratic presidential candidates contemplating sweeping health-care overhauls, what happens in Colorado over the next few months will be instructive. Lawmakers in Denver are preparing to vote on a state-sponsored health plan that would compete with private insurance and offer lower premiums. Its approval could embolden Democrats eyeing the White House.

Moderate Democratic candidates such as Pete Buttigieg, Michael Bloomberg, and Amy Klobuchar want to let people buy government coverage—like that offered to Americans 65 and older via Medicare—while their rivals to the left, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, would replace private insurance entirely with benefits funded by taxpayers. (Michael Bloomberg, founder and majority owner of Bloomberg LP, Bloomberg Businessweek’s parent, is seeking the Democratic presidential nomination.) Colorado’s proposal is more modest than what much of the Democratic field favors, since it relies on private insurers to manage the plans. But if the state is stymied by stiff opposition from hospitals and insurers, it could force voters to recalibrate their expectations for what a Democratic president could achieve.

Democrats won control of the state legislature in 2018, and Democratic Governor Jared Polis has put reducing health-care costs at the top of his agenda. Polis created an Office of Saving People Money on Health Care and promoted a number of ideas to lower spending, including the so-called public option. Colorado follows Washington state, which passed the first public health insurance option last year. Delaware, Massachusetts, and New Mexico have weighed their own versions in recent years. Polis says the measure is part of a necessary response to rising health-care costs, which he characterized as a crisis at a recent event in Washington, D.C. “People are fed up, and they want solutions.”

One of those fed-up people is Cindy Kahn, 59, who leads a social justice nonprofit and lives in the small mountain community of Carbondale, Colo. When Kahn and her husband began buying their own health insurance in 2018, they were “absolutely gobsmacked” at the $2,000-a-month premium, she says. An expensive surgery to treat a tumor in Kahn’s husband’s jaw added to the mounting costs. Kahn calls the financial toll “a toxicity in your life that lives with you. It’s like one step from the precipice.” Partly because of medical expenses, the couple decided to sell their home and consider moving to a bigger city where the market for insurance is more competitive. Kahn says she supports a public option but worries it may not be enough to make care affordable.

Colorado’s state-sponsored plans would start in 2022 and initially be targeted at the 7% of the population who buy their own coverage directly, instead of getting it from employers or through other government programs. The plans would offer premiums about 11% lower than what’s available today, on average, in the state’s individual insurance market, and as much as 17% lower in some places, according to an outline of the proposal by health and insurance authorities released last November.

To reduce costs, the state has taken aim at cutting how much money health-care companies can make. Authorities proposed that the public plans should be administered by private health insurance companies. The state would set the prices paid to hospitals according to “a clear, public, and transparent formula,” the outline says, rather than leaving insurance companies to negotiate rates. Insurers, in turn, would be required to offer the public option plans across the state, including in rural counties with no competition today. They’d also face tighter limits on how much premium revenue they can keep for administrative costs and profits.

While Democratic presidential candidates blame pharmaceutical companies and health insurers for the high price of care across the country, Colorado politicians are clashing most fiercely with the hospital industry. Health-care costs have continued to soar, even after the Affordable Care Act placed restrictions on health-insurer profits, says Kerry Donovan, a Colorado state senator who’s co-sponsoring the public option legislation. “The missing factor has got to be the hospital systems,” she says. “You don’t have to exactly have a doctorate in economics to come to that conclusion.”

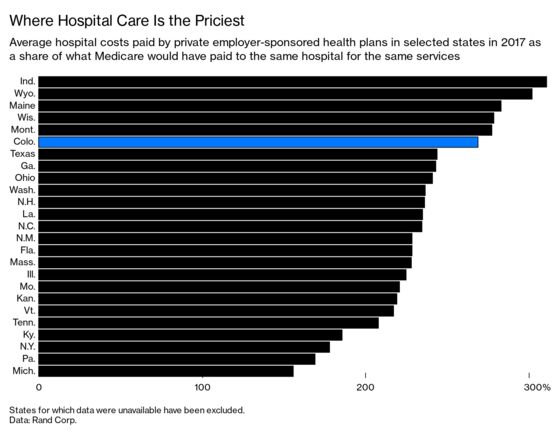

An analysis last year by Rand Corp., a policy research group, found that prices paid by commercial health plans to Colorado hospitals were among the highest in the 25 states for which analysts had data. Colorado hospital profits almost tripled from 2009 to 2018, to more than $1,500 per patient, according to a January report from the state. Economists have cited consolidation among hospitals and a lack of competition as factors driving up prices.

Hospitals, rejecting the idea that the state should set prices, have proposed an alternative that would limit total health-care spending in Colorado without interfering in the privately negotiated rates between insurers and hospitals. Targeting hospital profits is “punishing hospitals that are operating efficiently,” says Katherine Mulready, chief strategy officer of the Colorado Hospital Association. Amanda Massey, executive director of the Colorado Association of Health Plans, says insurers likewise “have significant concerns with the administration dictating the product, the price, and the places we must sell health insurance.”

A January mailer to Coloradans warned that the proposal would lead to higher costs and hospital closures, and that “politicians will be in charge of our health care.” The ad was paid for by a local affiliate of the Partnership for America’s Health Care Future Action, a national umbrella group of hospitals, insurers, pharmaceutical companies, and business interests formed to fight “Medicare for All” and similar policies. The group declined to say how much it was spending in Colorado.

Advocates for the public health option say industry is trying to kill it before a detailed legislative proposal has even been released. “There’s obviously a lot of national money being spent to protect the status quo,” says Dylan Roberts, one of the Colorado state lawmakers drafting the legislation. While the Democrats control the legislature, it’s not a given that Polis’s public health option will pass during the current session, which runs for about the next three months. By raising the prospect of hospital closures and prompting political opponents of the proposal to speak out, the industry-backed advertising campaign has put legislators under pressure to change the public option or walk away from it entirely. “The legislators, especially the ones who haven’t been paying close attention to this, are feeling the heat,” says Billy Wynne, a health-care consultant who advised on Colorado’s proposal but is no longer working for the state.

Colorado lawmakers will have to decide whether the state’s health-care costs are so high they warrant that kind of public interference, says Michele Lueck, president of the Colorado Health Institute, a nonpartisan research group. “This is kind of the classic example of, What’s the appropriate role of government intervention and regulation?” she says. “Are things so bad, are they so unaffordable for consumers, that the government has the right to intervene?”

Read next: The State With the Highest Suicide Rate Desperately Needs Shrinks

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rebecca Penty at rpenty@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.