What a Deutsche Bank Merger Could Mean for Germany

What a Deutsche Bank Merger Could Mean for Germany

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Since it was founded in 1870, Deutsche Bank was supposed to be a steward for German industry, helping the nation’s manufacturers finance overseas trade. Broken up into 10 banks after World War II, it regrouped and prospered along with West Germany and, much later, a post-Berlin Wall, reunified nation. It’s long strived to be more than just another lender. And since the 1990s, it’s tried to go toe-to-toe with U.S.-based powerhouses such as Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in global investment banking, the business of trading and underwriting securities and providing financial advice to corporations. Germany—and Europe—had nothing to match the Americans on that scope.

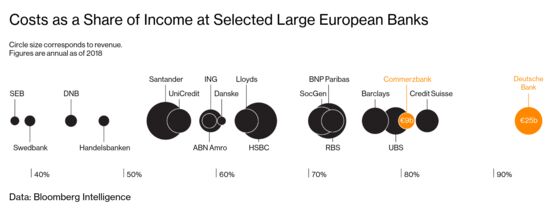

Even as its European rivals were scaling back their businesses and ambitions to adjust to the postcrash world, Deutsche Bank AG pushed further into new markets and new businesses, with a vision to project German financial might onto a global stage. Now that ambition is in tatters. The lender has burned through chief executive officers and launched four turnaround plans in recent years. It’s been trapped in a spiral of falling revenue and rising costs. Because of intense competition from Wall Street, it’s struggled to boost sales at the investment bank. But it’s also been reluctant to make deep cuts there, in part because the division also provides more than half of revenue. Europe’s sluggish economy and low interest rates haven’t given the bank much of a margin for error.

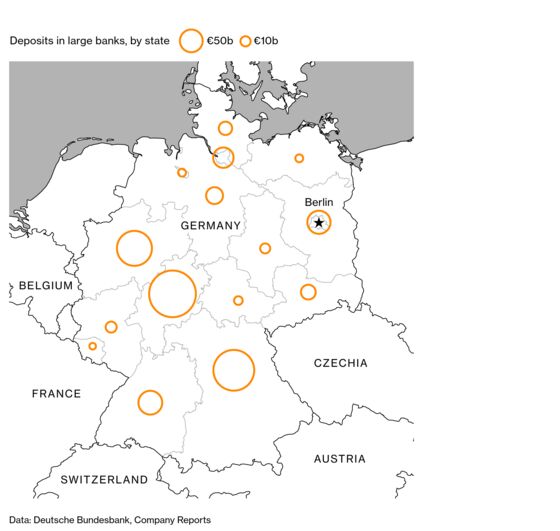

Today it’s considering a takeover of its main national rival, Commerzbank AG, which has also been in a slump. German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz has egged the deal on. The idea is that fusing two weak banks will forge a stronger one that can better withstand the next recession or financial crisis. The German government still holds a 15 percent stake in Commerzbank, a legacy of bailing out the lender a decade ago. European bankers and investors are riveted by what might happen next. If this deal fails, some speculate that a lender from outside Germany, such as Italy’s UniCredit SpA, will take a run at Commerzbank. Even Deutsche Bank could be vulnerable to a takeover from outside Germany. That foreign incursion would be a blow to the country’s pride.

Deutsche Bank’s future is a question of national importance. More than almost any other large country, Germany’s economic growth is dependent on its export industry—much of which relies on Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank to provide trade finance and other crucial banking services such as payments and risk management products. As concerns over the next recession are beginning to swirl in Europe, so are worries mounting that Germany may not have much of a domestic financial industry should it strike.

Scholz took an activist approach to the problem. In April 2018, a week after Christian Sewing became Deutsche Bank CEO, the finance minister drew him aside at a Prussian palace in Berlin during the German banking association’s annual reception. While it’s not known what was said, the 15-minute exchange marked the beginning of a thaw in relations between the government and the financial giant.

Even so, Sewing continued to resist a merger. He asked for investors’ patience as he focused on cutting expenses and stabilizing market share and said it would take several months before he would consider a deal as a solution to the bank’s woes. But he struggled to create a positive narrative. Over the past 12 months, Deutsche Bank’s shares have declined more than 37 percent.

A slew of awful headlines hasn’t helped. Earlier this year, it emerged that the U.S. Federal Reserve is reviewing Deutsche Bank’s handling of billions of dollars in suspicious transactions from Danske Bank AS, a Danish lender swept up in a €200 billion ($225 billion) money laundering case. Deutsche Bank said at the time it was providing information to law enforcement and regulators. In a separate matter, prosecutors in Frankfurt were looking into whether an obscure entity called Deutsche Bank Global Trust Solutions turned a blind eye when clients laundered dirty money and dodged taxes from 2013 to 2018. In November, 170 German law enforcement officers descended on Deutsche Bank’s headquarters and carted away boxes of files and computers. The bank denied wrongdoing and said it was fully cooperating with the inquiry. But the raid eroded confidence in the institution as it seemed to lurch from one fiasco to the next. By March 17, Sewing announced that the lender was starting formal tieup talks with Commerzbank.

There’s been a strong backlash to the potential deal. It would make a bank that’s already too big to fail about a third bigger. And it could eliminate as many as 30,000 jobs, say people familiar with the potential transaction. German newspapers have lambasted the proposal as a “disgrace,” and unions representing bank employees have vowed to boycott negotiations with bosses at both institutions if the idea isn’t abandoned. Moreover, Deutsche Bank may need to sell billions of euros of new shares to cover the cost of a merger, a move that would dilute the stakes of existing shareholders.

Even so, Sewing and Chairman Paul Achleitner see little choice but to consider a linkup, say people familiar with their thinking. Deutsche Bank has lost money in three of the last four years. Last year revenue from trading was 40 percent less than in 2014. “Something has to give,” says Oswald Grübel, the former CEO of Swiss banking giant UBS Group AG. But he adds, “They have huge problems to solve, and I think a merger would make the whole situation worse.”

One reason to come to the table is Deutsche Bank’s rising cost of funding. Banking profits are largely a matter of basic math—does your lending and other business earn more than it costs you to borrow? The weak profitability has made investors and credit rating companies more concerned about the bank’s ability to service its debt. It’s been forced to pay considerably more to borrow capital than its rivals have. Moody’s Investors Service pegs some of the bank’s bonds one notch above junk status and has a negative outlook on the lender. The bank says it’s doing everything it can to keep and even improve its rating. If a downgrade happened, “every financial risk committee on Wall Street would call a meeting and say, ‘Can we, or should we, continue to do business with Deutsche Bank?’ ” says Barrington Pitt Miller, a money manager with Janus Henderson Group Plc, which holds shares of the lender.

By merging with Commerzbank, Deutsche Bank would increase its deposit base by more than 40 percent, which should help lower funding costs. It would also expand the proportion of income from more stable business lines. The deal could provide another benefit: It may help preserve the bulk of the company’s investment banking franchise in London, New York, and Asia.

This latest episode in Deutsche Bank’s long-running drama has been building since the term of Sewing’s predecessor as CEO. John Cryan, a Briton and former chief financial officer at UBS, had tried to shake up the German lender for three years. He derided investment bankers for expecting lavish pay simply “for turning up to work” and slashed their bonuses. He pushed hard to overhaul the company’s convoluted IT infrastructure, which ran more than 40 operating systems, and to install controls against misconduct. He also vowed to trim expenses and boost revenue.

Cryan’s changes were designed to deliver what he called “sustainable profits.” Yet year after year, shareholders were peeved by the company’s inability to produce just that. They weren’t happy about slow progress in cutting expenses, either. When Deutsche Bank recorded only €26.4 billion in revenue in 2017, its worst performance since the crash, the board decided not to keep Cryan around. It replaced him in April 2018 with Sewing, then head of the private and commercial bank. Sewing is the first executive to lead Deutsche Bank in almost two decades who wasn’t from investment banking.

The board was, in effect, conceding that despite three turnaround plans since 2015, management was still failing to reverse the bank’s slide. Several analysts and shareholders blamed the investment side—especially its U.S. operations. But when Sewing unveiled his own turnaround plan a few weeks after taking charge, investors saw it wasn’t much different from Cryan’s. Once again, management decided to apply only limited cuts to the divisions. Investors punished Deutsche Bank’s stock.

Chairman Achleitner has also come in for criticism. Glass Lewis & Co., an influential corporate governance advisory firm based in San Francisco, said it had “substantial concerns” about the progress under Achleitner. The appointment of Sewing, it said, was likely the chairman’s “final chance” to get things right.

As the bank’s struggles deepened, anxiety mounted in Berlin. Scholz, the new finance minister, and his deputy, Jörg Kukies, were becoming concerned that Deutsche Bank couldn’t rebound on its own. A merger with Commerzbank looked like a solution. It could put the bigger bank on a sounder footing without investing new taxpayer funds.

Scholz, a former leader of the left-leaning Social Democratic Party, and Kukies arranged a series of discussions involving Achleitner, Sewing, and Commerzbank CEO Martin Zielke, according to people familiar with the talks. The ministers were careful not to speak publicly about a potential deal, but they also didn’t shoot down news reports about the talks and the government’s tacit support for the idea of creating a national banking champion.

Deutsche Bank’s travails are the last thing Germany needs as it copes with a weakening economy and a surge in political populism. A decade after the global financial crisis and long since most of Deutsche Bank’s counterparts in the U.S. and Europe have rebounded, a nation that shuns credit cards and budget deficits somehow has a bank problem on its hands. While Chancellor Angela Merkel has distanced herself from the negotiations, Deutsche Bank’s inability to recover under its own power puts her in an awkward position. For years, Germany has demanded that the countries in the euro zone clean up their banking industries and make sure they don’t need taxpayer-funded bailouts. But now, if there’s a combination, Berlin may wind up owning about 5 percent of the country’s largest bank, mainly as a result of Deutsche Bank’s strategic missteps.

The takeover “would reinforce the too-big-to-fail problem that could eventually fall back on the German taxpayer,” says Danyal Bayaz, a Green Party member of the Bundestag and member of the legislature’s finance committee. “If the banks haven’t managed to develop a viable business model 11 years after the financial crisis, there is no way that taxpayers should be put in a position where they could be asked to step in again.”

Deutsche Bank’s troubled trading arm will likely be considered by European banking regulators looking at the proposal, according to people familiar with the matter. They’ll want to know how much the bigger bank would still rely on the securities unit.

It’s unclear how the combined institution would be reorganized or who would make up its executive suite and supervisory board. The benefits of a deeper deposit base might be eclipsed by the overwhelming challenges of merging two complex organizations. In an era when digitalization is a top priority in banking, fusing the IT systems of Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank could be the last thing either one needs. Not unlike public railway projects, such undertakings are fraught with blown deadlines and cost overruns.

No company knows that better than Deutsche Bank: Nine years after it bought German consumer lender Postbank for about €6 billion, it’s now spending an additional €1 billion trying to consolidate the companies’ systems, and the job still isn’t done. A merger with Commerzbank “would tie the bank down for years to come and cause huge upfront costs, while any savings would come much later, if at all,” says Isabel Schnabel, a finance professor at Bonn University and an adviser to the German government.

The problem is that Deutsche Bank may not have much of a choice. If the deal falls through, Sewing would be left with a fraying turnaround plan, and investors would likely demand that he rapidly come up with a new one. It’s just not clear what that could be other than even more cuts to a bank that’s unsuccessfully tried to shrink itself to profitability for the better part of a decade.

That’s why some, including Harry Harutunian, an analyst with Olivetree Financial Ltd. in London, see a tieup as the least bad option. Slashing costs too deeply in the investment bank will limit its ability to increase revenue, likely hurting profits and putting the bank at risk of a credit rating downgrade. It’s a vicious circle, to use the phrase of Deutsche Bank CFO James von Moltke. And there’s little hope the lender can pick up a “revenue tailwind” from Germany’s commercial banking market, which has long been a tough place to make money because of low interest rates and numerous state-backed competitors. That may be why, even now, the bank continues to add staff in markets such as the Middle East and South Africa in a hunt for business.

The path of cuts and more cuts might put Deutsche Bank in a position similar to that in 2009 of the Royal Bank of Scotland, a sprawling, intercontinental player then in need of wholesale restructuring. It took RBS a decade and £15 billion in reorganization costs to get back to the right size. “Deutsche Bank will have to take less risk in investment banking, and it will continue to lose relevance as an international player,” says Klaus Fleischer, a finance professor at Munich University of Applied Sciences who’s studied the bank for years.

Whether Deutsche Bank merges or goes it alone, it will also need to end its habit of slipping into political or legal scandals. It wasn’t until 2017 that its management board started getting a detailed picture of how its many businesses signed up clients and monitored and controlled risk. That year, Deutsche Bank agreed with regulators in the U.S. and the U.K. to pay $630 million to settle allegations that it helped wealthy clients transfer $10 billion out of Russia from 2011 to 2015 in violation of money laundering laws.

More recently, Adam Schiff and Maxine Waters, the Democratic heads of two powerful committees in the U.S. House of Representatives, started hiring lawyers and readying subpoenas as they opened investigations to examine Deutsche Bank’s dealings with President Donald Trump. Before 2016, the bank made hundreds of millions of dollars in loans to the Trump Organization at a time when the group’s numerous bankruptcies had cut off funding from most other lenders. Deutsche Bank declined to comment on the inquires, and the Trump Organization didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Maybe Europe does need its own investment bank as an alternative to U.S. powerhouses. The question now is whether the Frankfurt lender can ever be that institution—and what path the bank should ultimately take to help Germany prosper. —With Birgit Jennen, Harry Wilson, and Nicholas Comfort

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net, Bret Begun

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.