What $64 Million in PPP Loans Did for One Neighborhood

What $64 Million in PPP Loans Did for One Neighborhood

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Tim Keck thought the end for The Stranger was so likely in early March that he had a tearful dinner with his family to tell them it might go under. The virus was already spreading rapidly in Seattle, where he’d started the irreverent newspaper in 1991. The publication—and Keck’s other outlet, The Portland Mercury—depended heavily on ads from clubs, movie theaters, restaurants, bars and the like. His company, Index Newspapers, also made money from hosting film festivals and running a ticketing service for events. “As a company, we were diverse—but diverse within the category of ‘people getting together,’” he says. “If there was a shutdown, it looked like we were going to be dead.”

The shutdown, of course, happened. But Keck’s business didn’t die. In mid-March, The Stranger announced that it was halting its print edition and cutting staff to conserve resources so it could cover the news as best it could until it ran out of money. It put out an “S.O.S.” to readers, and many donated. A few advertisers kept paying their bills into April. Then, in early May, Index Newspapers got $1.2 million from the federal Paycheck Protection Program. Keck was stunned. He’d mostly bootstrapped his businesses ever since he started the satirical newspaper The Onion with $5,000 from his mom. Bailouts, he thought, were for big corporations. “We’ve never really gotten help,” he says.

To sift through the recently released data on the $521 billion small-business loan program is to experience the economic trauma of the past few months in a new light. I spent several hours with the entries for Seattle recently, and was struck by just how many organizations and businesses took the loans. Sure, it was potentially free money. (Under the terms of the program, the loans turn into grants if borrowers meet certain criteria.) Yet it’s likely that most of these establishments needed the funds to tide them over. The city’s zoo is listed, as is the art museum and the Seattle Times. So are the coffee roaster near my home, a respected affordable housing developer, and the restaurant group of a James Beard Award-winning chef. It’s hard to imagine the city without them.

In recent months, almost all media coverage of the program has focused on the rocky rollout and galling examples of who took loans, including big-name law firms, Wall Street managers, and companies with ties to President Donald Trump. Inconsistencies and inaccuracies in data about the program have only made it harder to determine how well it’s worked and whether funds were handed out equitably. (Early evidence suggests not.) A whole generation of journalists that earned their stripes during the global financial crisis seemed primed to find fault in a program that was hastily cobbled together. But all this should not obscure a fundamental truth: Millions of small businesses needed money—and fast.

In many ways, Capitol Hill—the neighborhood where Keck built his business—turned out to be a reasonably representative slice of the program for King County, which includes Seattle and its suburbs. It’s chock-full of of companies that were eligible for the program—some large enough to get millions of dollars, some so small that they qualified for only a few thousand. As a center of Seattle nightlife, the neighborhood also has many businesses that were bound to be affected by a three-month lockdown and ongoing social distancing measures.

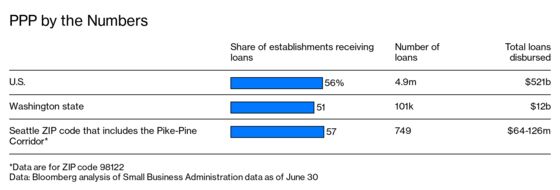

Federal data released last week show that nearly 750 businesses, or about 60% of the establishments in the ZIP code that includes Capitol Hill’s Pike/Pine commercial district, got loans. That uptake makes it slightly above average for Seattle and its suburbs, but not much so. At least $64 million was doled out through the program, putting the neighborhood in the top quartile for King County as a whole. The Small Business Administration provided ranges only for loans above $150,000, so the total disbursements could have been as high as $126 million.

Beyond the data, interviews with business owners in the neighborhood paint a picture of a program that, after a confusing rollout, was crucial in helping companies weather the shutdown but was also far from sufficient. It’s too early to be able to make any conclusions about the program’s effectiveness at bringing people back to work. Rules for what is to be forgiven keep changing, and a resurgence of the virus now threatens to throw the reopening into reverse. Many jobs won’t need to be filled again for a long time. Meanwhile, business owners are dealing with all sorts of hassles—some related to PPP.

Take Jon Milazzo, the co-owner of a retailer called Retrofit Home. After laying off staff at the end of March, she and her business partner Lori Pomeranz got a $48,000 PPP loan that allowed them to pay some rent and bring back their four employees in May. They worked diligently through the month to get furniture, home goods, and other items in their store photographed so they could build an online store.

Then, in June just as King County was allowing retailers to reopen, Milazzo and Pomeranz were forced to shut and lay off all their employees again because a protest zone had taken root a block away, around the Seattle Police Department’s East Precinct building. (The cop-free area, called the Capitol Hill Organized Protest, or CHOP, drew international attention and has since been cleared.)

In the middle of it all, Bank of America, which made Retrofit’s loan, said that there was a discrepancy in the payroll calculation that meant the small business would have to give back $1,200, Milazzo says. “I said, ‘Jesus Christ, you’re handing out million-dollar loans to people like Kanye West like candy, and you’re calling me?’” The bank declined to comment, saying it doesn’t discuss client matters.

Other businesses were confused about the rules and ended up applying for less money than they could have. Zack Bolotin, the owner of Porchlight Coffee & Records, didn’t realize he could roll his own wages into the calculation, so he ended up getting a loan of less than $10,000. He spent two months working the shop himself and brought back only two of his three employees last month. He has an offer out to a new employee but isn’t rushing to fill the vacancy. “I’m not on-my-knees grateful,” he says of the PPP loan, “but I’m not poo-pooing it.”

Makini Howell, the owner of Plum Bistro, initially used her PPP loan to hire back staff to remodel her restaurant in accordance with the new social distancing guidelines. But after reducing the number of tables from 14 to 6 and removing all nine barstools, she’s now worried that it’s going to be months before business comes back. “I think we miscalculated,” she says. “We thought people were going to be like, ‘Over it. Let’s go.’”

Her businesses used to employ 35 people full-time. Now, it has 14, including Howell. She would have liked to hire back the remaining half of the staff, but they weren’t available. She’s saving some of her PPP loan to see how things pan out in what are typically her slow months. “Winter is notoriously hard, so I would like to be prepared”—especially now that the virus is surging again, she says. “I can tell people are getting kind of scared. They’re pulling back.”

For Keck, the co-owner of The Stranger, the money allowed him to pay a decent severance to some employees he knew he couldn’t bring back. He also rehired two editorial staffers for each of his papers and gave them a freelance budget, which helped them cover the protests over police brutality in June. (Some of the most intense clashes with police unfolded right outside The Stranger’s former office, which the paper opened up to other journalists.) Even so, Keck is still banking a portion of his loan, figuring that the virus is going to make things worse before they get better.

Mostly, he says, it’s given him enough breathing room to imagine what his business might become. He’s rehired someone to run membership services, since reader contributions will be key for the future of his papers. And he brought back another person to work with organizations that want to produce ticketed online events. “It’s been utterly instrumental in us surviving,” he says. “In order to evolve, you need time. And it gave us time.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.