Warby Parker Wants to Be the Warby Parker of Contacts

Warby Parker Wants to Be the Warby Parker of Contacts

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- One morning in September, Dave Gilboa stood on a staircase at Warby Parker’s library-like headquarters in New York to tell employees about the eyewear retailer’s future. There had been some modest milestones to celebrate, including a new collection of frames handcrafted in Italy and a store opening at the King of Prussia shopping mall outside of Philadelphia. But the big reveal was on Gilboa’s face. Or rather, it was on his eyeballs.

On Nov. 19 the company plans to unveil Scout, a line of daily contact lenses. It’s the first time Warby Parker Retail Inc., whose $95 tortoiseshell frames are ubiquitous in coworking spaces and third-wave coffee shops, has expanded beyond eyeglasses since Gilboa and co-Chief Executive Officer Neil Blumenthal started the company almost a decade ago. At $440 for a year’s supply, the lenses will be slightly cheaper than many daily contacts but will be sold with what Warby says will be a much improved ordering process.

Gilboa’s speech was one of several events Warby held this fall to get its more than 2,000 employees appropriately excited for a product that seems impossible to get excited about. “This feels orders of magnitude larger than everything we’ve done, from the branding to it being an entirely new product category,” Gilboa says in an interview with Bloomberg Businessweek after the staff meeting.

If anyone could make contact lenses cool, it would be Warby Parker. The company is often credited with creating the direct-to-consumer craze. (“Direct to consumer” is a fancy term for product makers who eschew wholesalers and sell their stuff on the internet.) Investors have pumped enormous sums into millennial-friendly businesses marketed as “the Warby Parker of X.” Allbirds, Casper Sleep, Dollar Shave Club, and Glossier—the Warby Parkers of sneakers, mattresses, razor blades, and makeup, respectively—each achieved valuations of $1 billion or more thanks to clever social media marketing and clean-looking websites. Those are the most successful Warby clones, anyway. There are also Warby Parkers of short-shorts (Chubbies), vitamins (Care/of), dog toys (BarkBox), and untucked buttoned-downs (Untuckit).

And then there are the other direct-to-consumer eyewear businesses: the Warbys of Warby, to take the snowclone to the point of absurdity. These include Zenni Optical, Coastal, Ambr Eyewear, and GlassesUSA. Many of them offer similar frames at even cheaper prices. Sucharita Kodali, an analyst at Forrester Research Inc., says this competition means Warby Parker will have to transform itself into something more than a cool eyewear brand before its cool wears off. “Whether or not Warby turns into a hugely transformational business remains to be seen,” she says.

Can contact lenses, a commodity product poked onto your corneas, be the key to this transformation? Contacts require serious regulatory oversight; the U.S. Food and Drug Administration classifies them in the same medical device tier as hearing aids and pregnancy kits. And Warby is hoping to push the envelope by one day letting consumers take an eye test and update their prescription using only an iPhone and a MacBook.

Unfortunately, if the thickness of a contact lens is even a micron off, that can lead to infections. Selling contacts, says Sally Dillehay, an optometrist who’s worked in vision research for three decades, is much more involved than selling “tube socks”—referring perhaps to Bombas, the Warby Parker of tube socks. “We’re talking about a piece of plastic that sits on your eye, right? Your most important sense,” she says. Gilboa and Blumenthal say they are bringing the same care and safety precautions to contacts as they have to prescription eyeglasses.

But there’s also the obvious marketing challenge. A really nice pair of contact lenses inspires none of the feels that can be conjured by a pair of trendy spectacles or wayfarer shades. But if Gilboa and Blumenthal can actually create a fashion brand for contacts, they’ll have pulled off an audacious marketing feat, on the scale of the invention of “certified pre-owned” used cars and the duck that quacks about supplemental insurance. “They’re vastly different,” Blumenthal acknowledges, comparing Warby’s core glasses business with its new one. “Contacts are designed to be invisible.”

Warby Parker’s eyewear is often thought of as a fashion accessory, yet industry observers say its glasses are actually just a small part of its popularity. Katie Finnegan, a retail consultant who previously led Walmart Inc.’s store-of-tomorrow incubation efforts, says what has most distinguished the brand is its service, including a home try-on offering that allows customers to order five pairs of glasses online and try them on for free. “They have this je ne sais quoi that transforms them from a transactional errand to an emotional experience,” Finnegan says, referencing how the company names its frames after the literary characters of Jack Kerouac, Harper Lee, and other fiction luminaries. “Their glasses became a piece of your identity.”

The company’s Rockefeller Center store is a marvel of midcentury design. Glowing shelves accent frames uniformly spaced apart, and floor associates in blue smocks hover around low walnut tables. On a recent afternoon, Gilboa and Blumenthal strode through the store pointing out displays of glasses and a reproduction of a Stuart Davis mural they commissioned.

Scout lenses, though, won’t be on display here like their glasses. They’ll mostly be sold online, and in Warby's new “eye exam suites,” one of which can be found by going through a back door and up two flights of stairs. The hip doctor’s office feels a bit like a vinyl-record listening room, with slate gray wallpaper and soft lighting. Warby is tripling its number of in-house optometrists, to 80, and adding suites like this one to 40 more of its stores this year.

The idea is to foster the antithesis of Gilboa’s own experience when he was first prescribed contacts at age 12. “It was sterile, scary, and uninviting, more of a medical purchase than something I was excited to try on,” he remembers.

He and Blumenthal were MBA students at Wharton when they started discussing the idea that would become Warby Parker in 2010. Their plan was to disrupt Luxottica, the Goliath to their David. The eyewear conglomerate, now known as EssilorLuxottica SA after its 2018 merger with the French lensmaker Essilor, is worth $67 billion and controls manufacturing and distribution for most eyewear brands on the planet—Ray-Ban, Persol, Oliver Peoples, you name it. It owns mall staples such as Sunglass Hut and LensCrafters and operates EyeMed Vision Care LLC, the second-largest vision insurance provider in the U.S. (which doesn’t include Warby Parker in its network). Gilboa and Blumenthal designed acetate frames and sold them on the web, moving more than 100,000 pairs of glasses in 2011. Several years later, Warby Parker began opening physical stores, hitting 64 locations in 2017. (There are 112 today.)

Warby’s growth even caught the attention of Mickey Drexler, the retail icon who made Gap khakis cool in the 1990s and then did the same for J.Crew in the 2000s. Drexler joined Warby’s board and invested in the company, which has raised $290 million in financing from venture capital firms including First Round Capital, General Catalyst, and Tiger Global Management. Gilboa and Blumenthal say other potential investors suggested they consider following the examples set by Groupon Inc., a faddish marketplace for store discounts, and ShoeDazzle, a formerly hot fast-fashion subscription service, but they said no.

Blumenthal and Gilboa also resisted suggestions to expand into additional categories, even as more and more direct-to-consumer replicas took off. One of their co-founders, Jeff Raider, created Harry’s Inc., a different Warby Parker of razors that was acquired in May for $1.4 billion by Edgewell Personal Care Co., the consumer-product company that owns Schick and Playtex. Two other former executives, Jen Rubio and Steph Korey, left to develop Away, the Warby Parker of luggage, which also boasts a $1.4 billion valuation. (Warby Parker was valued at $1.75 billion in its last funding round in March 2018.)

They considered competing with Shinola, the Warby Parker of watches, and explored whether they could sell their sales software to other companies, but the possible return on these investments wasn’t big enough. Instead, they decided there was more promise in optical services. Selling contacts and doing more eye exams represented an $11 billion market, “bigger than, like, selling mattresses,” Gilboa says, a knock at Casper, or maybe Helix, Leesa Sleep, Tuft & Needle, or the myriad other Warby Parkers of bedding.

Roughly 40% of their customers already wore contacts, and when the company offered third-party lenses in some markets as a test in June 2018, sales increased an average of over 75% each month that year. At the Rockefeller Center store alone, they became a top 10 bestselling product.

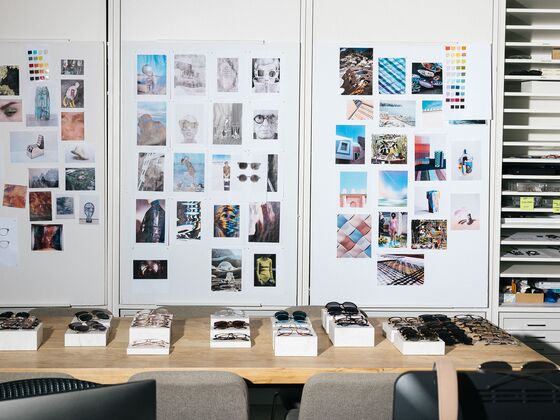

But what would the Warby Parker of contact lenses be? Customers could rarely identify a single brand by its name. (“They all have names like ‘AquaComfort Plus’ and ‘AquaSoft Moist,’” Gilboa jokes.) So a skunk works team rounded up every contact lens it could find, studying comfort, casings, and checkout processes. They discovered problems in the pricing schemes for daily contacts, which are typically obfuscated by mail-in rebates and service charges. Then there was the tear-off packaging, which usually entails finger-fishing for a lens drowning in contact solution, then squinting to see if it’s upside down. Gilboa and Blumenthal found a manufacturer in Asia that could slip the lenses into a flatter sleeve that Warby Parker promises will always keep the contacts facing the right way.

About 70% of glasses are purchased at the same time as prescriptions are written, which puts Warby Parker at a disadvantage. “If a doctor prescribes you Lipitor, he’s not selling you that drug. But with eye doctors you get the exam, and they upsell you on glasses and lenses,” Gilboa says. “It’s ‘exit through the gift shop,’” Blumenthal adds. By increasing the number of staff optometrists and building eye exam suites at every new store, he and Gilboa say they can goose their own sales. According to a source familiar with the company’s financials, revenue grew 35% last year, but just a single-digit percentage of Warby Parker’s customers have historically gotten prescriptions and eyewear simultaneously at their stores.

EssilorLuxottica has more than 9,000 stores, a figure Warby Parker can’t hope to compete with anytime soon, so instead the company has focused on using software to check prescriptions. Through the Warby Parker mobile app, shoppers can update their glasses prescription for $40 with a self-administered vision test, which they hope to use for contacts too in the future. The service uses your phone and laptop to test your sight and sends the results to an eye doctor to confirm the prescription. But these digital tests encompass only a portion of what a doctor would do in an in-person exam, including inspections for glaucoma and other eye diseases.

Some optometrists view this form of telemedicine as an unsafe threat and are fighting services such as Warby’s app at a state and federal level. Hubble Contacts, another internet-centric eyewear company, has been accused in media reports of failing to properly verify prescriptions, which can cause vision problems, an allegation the company denies. The FDA has recalled the at-home vision test made by a similar startup, Visibly, classifying it as a medical device that needs approval before it’s marketed. The company’s CEO, Brent Rasmussen, says it is working to win FDA approval. Georgia, Michigan, and New Mexico have effectively banned online vision tests, and a number of other states are considering similar prohibitions. “These exams are in no way, in any stretch of the imagination, an eye examination,” says eye doctor Barbara Horn, president of the American Optometric Association. “They have not proven to be accurate, and they haven’t passed the premarket approval.”

Gilboa and Blumenthal don’t appear fazed by the skepticism. In an interview in which they arrived dressed as pop-rock duo Hall & Oates (the corporate Halloween party was that evening), they describe their digital medical service as a complement to, rather than a replacement for, in-person eye exams. They contend that punishing the entire industry for the “careless and sloppy” practices of bad actors is not in the interest of public health. “It’s anti-innovation, anti-consumer, and frankly anti-American,” Blumenthal says, the seriousness of his message undercut slightly by his leopard-print shirt and long blond wig.

Gilboa, sporting a rhinestone jean jacket and bulbous curly black wig, adds that a blanket ban against vision telemedicine is “the equivalent of saying, ‘Autonomous vehicles are not ready for prime time today, so we’re just going to ban them in perpetuity, instead of figuring out the safety regulations and data we need to see to allow this technology.’”

They argue that their app may give their optometrists ways in the future to identify eye diseases earlier. In the meantime, they’re lobbying for pro-telemedicine regulation and pushing more vision insurance companies, which mostly allow customers only out-of-network reimbursements for Warby Parker lenses and optometrist visits, to cover them. If they don’t, Blumenthal says, “it’s going to suck for them because we’re just going to keep taking their market share.”

Off a highway near a Sunoco gas station, Warby Parker’s Sloatsburg, N.Y., factory is humming. During the week, 100 employees operate production lines almost around the clock, making this optical lab an hour north of New York City one of the largest in the country. Here, workers process eyewear orders, match frames to prescriptions, and send them through vending-machine-size lens cutters that churn out nearly 50 pairs per hour. The factory is bright and modern, designed like a Warby Parker store, and growing fast: It’s more than doubled its output since opening in 2017, and the company is currently increasing production by a third. Gilboa and Blumenthal decided to build the facility after some customers complained about how long it took to get their glasses—now they say order fulfillment times have improved more than 10%.

Spend time with Warby Parker’s founders, and you’ll hear them talk endlessly about such under-the-hood efficiencies, the implication being that the company is much more than pretty frames. This can sometimes come off as a bit strained: At one point the two men engage in a lengthy discussion about the advice they received from New England Patriots head coach Bill Belichick, a football strategy genius with no known fashion credentials. “Bill is an amazing capital allocator, a great value investor,” Blumenthal says, referring to the coach whose sideline look generally consists of a hoodie with the sleeves cut off and a pair of sweatpants.

This is, of course, all part of Warby Parker’s retail theater, but it may also help the company evolve beyond a snowclone of an internet brand and into something greater. Forrester’s Kodali says this transformation is especially important for the proliferating capital-bloated VC-backed companies. “A lot of these retailers are overrated,” she says. “They’re not billion-dollar brands. They’re modest-sized niche companies.”

Gilboa and Blumenthal agree, but they argue that this critique doesn’t apply to Warby Parker. After touring the Sloatsburg optical lab, they note that their eyeglass business is profitable, and that they believe Scout contacts will open them up to an even larger group of customers. They’re not interested in an initial public offering just yet; they say they don’t need the capital. “If we viewed going public as an exit, we’ve might’ve tried to grow as quickly as possible and gotten as much hype as possible,” Gilboa says. “We want to build an enduring brand.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Max Chafkin at mchafkin@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.