Inside Walmart’s Corporate Culture Clash Over E-Commerce

Inside Walmart’s Corporate Culture Clash Over E-Commerce

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Not long ago, a Walmart Inc. store manager asked the company’s e-commerce department if it could send over the details of any online orders that customers were planning to pick up at the store that day.

The internal network that usually zapped those orders from the website to the stores had temporarily crashed. The online team mocked the request, asking how that could be done with the network down. The store manager’s response: Find an adult to show you how to use a fax machine.

The episode illustrates a broader culture clash at the world’s largest retailer, one that pits its Bentonville, Ark., headquarters against the coastal outposts that manage most of its online business.

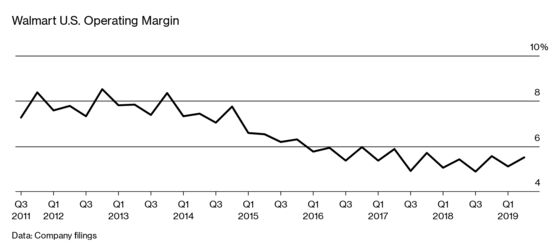

While it hasn’t dented sales, the internecine strife has had an impact: Investments backed by the digital squad have crimped Walmart’s already-thin profit margins, which have touched historic lows in recent quarters. Some high-profile acquisitions and other strategic moves have cratered. Talented executives from both camps have departed, while heralded new hires haven’t jelled.

The two groups had been kept separate since Walmart launched its website more than two decades ago, creating internal fiefdoms and power struggles among managers who don’t see eye to eye and rarely even communicate.

Now those disparate groups are being integrated and streamlined, to fulfill Chief Executive Officer Doug McMillon’s vision of transforming the big-box behemoth into a so-called omnichannel retailer. That’s industry jargon for the ability to satisfy the customer wherever and however she shops—in the store or online, in rural Bentonville or hipster Brooklyn.

“Our customers want one seamless Walmart experience,” McMillon said in a July 19 memo outlining the integration, which merged the e-commerce group’s finance and supply chain teams into their counterparts on the brick-and-mortar side.

But seams exist inside the company Sam Walton founded. The push to be all things to all shoppers has taken Walmart outside its comfort zone, which is selling low-priced household staples to Americans who largely live paycheck to paycheck. The traditionalists say Walmart’s attempts to move upmarket and gain more digital cred have burned through money that could have been better spent elsewhere. Those on the coasts, meanwhile, say they’re hamstrung by a dizzying matrix of management layers, which can slow decisions and stifle innovation.

In today’s retail world, Walmart can ill afford a culture war. Amazon.com is a colossus, capturing almost 40% of all e-commerce spending in the U.S. from millions of loyal Prime customers, and hungrily eyeing Walmart’s dominant position in groceries. Target has gotten its groove back, winning over style-conscious soccer moms and opening small stores in urban markets, something Walmart was never able to accomplish. Discounters such as Dollar General and Germany’s Aldi, meanwhile, have entangled Walmart in a price war that already has cost it billions and could get even more brutal if the U.S. slips into a recession.

That’s prompted some investors to seek greener pastures elsewhere in retail. Over the past two years, Walmart’s shares have trailed not only Amazon’s but those of Target, Dollar General, and warehouse chain Costco Wholesale Corp.

Culture clashes are common when hidebound companies grapple with changing times and tastes. Sears, once America’s biggest retailer before Walmart supplanted it, tried to revive its apparel business in 2002 by spending $2 billion for preppy-apparel maker Lands’ End. The deal was an abject failure, though, as Sears managers clumsily tried to shoehorn the brand inside Sears’s stores. Sears finally spun off the unit in 2014.

Walmart’s leaders say the tension between the dot-commers and the stores is no big deal. “It’s perfectly understandable, even good,” says e-commerce chief Marc Lore, who sold his millennial-focused startup Jet.com to Walmart for $3.3 billion in 2016. “It’s not unhealthy in any way.” McMillon, his boss, agrees: “There’s a cultural change under way at Walmart, and we are enjoying it,” he told investors last year.

Not everyone is enjoying it, however. The company recently jettisoned ModCloth, a women’s clothing site that specializes in vintage-inspired frocks, just two years after acquiring it. It’s entertaining outside offers for Jetblack, an unprofitable text-based concierge shopping service for affluent New Yorkers, and just replaced its CEO. Vudu, a video-on-demand service Walmart bought in 2010 only to see it get leapfrogged by Netflix and other subscription-based services, could also be on the block, tech media site the Information reported on Oct. 30.

The digital divestments suggest that the online crew is losing the struggle, but the traditionalists have suffered as well. Walmart’s U.S. stores chief, Greg Foran, last month gave up one of the most powerful jobs in retail to run an airline in his native New Zealand. Foran, according to people who worked with him, had grown frustrated with the amount of time and money spent on things that didn’t matter to him, like Store No. 8, an internal incubation arm that promises to “transform the future of retail” by exploring things like virtual reality.

“Walmart is an execution culture,” Kirthi Kalyanam, executive director of the Retail Management Institute at Santa Clara University. “It’s not a culture where people come with a lot of chest-thumping ideas. It’s about getting stuff done.”

Foran was one of those who got stuff done, having revitalized Walmart’s moribund U.S. stores in recent years to produce 20 consecutive quarters of increases in same-store sales, the key gauge of a retailer’s health. Now he’s gone, and some of his acolytes could follow him out the door.

Lore, meanwhile, has seen his former startup sidelined as Walmart has decided to focus resources on its main website, Walmart.com. Jet’s president was removed over the summer, and the unit’s dedicated head count is down from more than 300 staffers to about a dozen. A serial entrepreneur, Lore chafes under the company’s stifling layers, but says he isn’t going anywhere. (Any departure seems particularly unlikely before September 2021, when the last of the restricted shares he received upon selling Jet, worth about $420 million, fully vest.)

“At a startup, you get a few people in a room and make a decision and go,” Lore said at a recent e-commerce conference in New York. “There are a lot of stakeholders at a large company, and it takes longer.”

Bureaucracy is endemic at big companies, but attempts to break up silos can backfire. General Motors Co. CEO Mary Barra has labored for years to bust up the Cadillac maker’s powerful fiefdoms, in part by bringing in more external hires and pushing managers to act more like entrepreneurs. In 2014, GM hired Dave Townsend, a lead designer on the Samsung Galaxy S phone, to work on Cadillac’s troubled Cue system, a touchscreen that controls heat, air conditioning, and audio. Townsend wanted to open a studio and unleash for GM the kind of expertise and creativity that smartphone companies such as Apple and Samsung have, but he met resistance, people familiar with the matter said at the time. He left after seven months.

McMillon has employed some of Barra’s tactics, installing Lore and some of his deputies to run Walmart’s U.S. e-commerce division not long after acquiring Jet. McMillon’s goal, he said at the time, was to “protect Marc and Jet from the Walmart bureaucracy that exists”—while at the same time inspiring Walmart’s legacy business “to move even faster.” That’s proved to be more challenging than he expected.

Walmart has been through cultural upheavals before. In the 2000s, then-CEO Lee Scott hired a slew of business school graduates to bring a more analytical approach to the retailer’s operations, which were straining from years of explosive growth. But their presence rankled the more rough-hewn managers who received their education inside Walmart’s stores and warehouses. The strife, dubbed “Boots vs. Suits,” distracted senior management and opened a window that rivals like Amazon exploited.

The current culture clash stems from McMillon’s long-standing desire to adopt the trappings of technology companies—the emphasis on innovation, the willingness to fail fast. McMillon fancies himself a bit of a gadget guy, and fondly recalls his time spent as a merchandising manager in the electronics department, where he got to take some trips out to Silicon Valley. There he met with famed venture capitalist Jim Breyer, a member of Walmart’s board at the time.

Back then, e-commerce wasn’t really taken seriously in the cramped corridors of Walmart’s corporate headquarters. Its website was first set up under a separate standalone company, and featured a clunky digital version of the greeter who welcomes shoppers at each store. Walmart’s store managers blanched at putting the site’s URL on shopping bags, for fear of sacrificing sales to the fledgling dot-com unit.

That’s the culture McMillon inherited when he became CEO in 2014, and he set out to change it. “We’re building an internet technology company inside the world’s largest retailer,” he told investors that year.

To do so, he picked the brains of tech luminaries such as Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg and Apple’s Tim Cook, huddled with management gurus like Harvard’s Clayton Christensen, and added Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom to the board of directors. Greg Penner, a venture capitalist and the son-in-law of Rob Walton, became board chairman, signaling that a new generation was in charge.

Advice from tech geeks wasn’t enough, though: McMillon needed to inject some digital know-how straight into Walmart’s bloodstream. Lore was the answer. Walmart had missed out on acquiring Lore’s previous startup, Quidsi, best known for its Diapers.com website, which Amazon gobbled up in 2010. McMillon wouldn’t make the same mistake, and paid what many considered too dear a price for Jet, which was unprofitable and burning through cash. But it delivered Lore, the change agent.

“If Marc can be Marc within this company, great things are going to happen” McMillon said a month after the deal closed.

Plenty happened, but not all of it great. Walmart’s website grew rapidly and aggressively, adding millions of products and acquiring such brands as ModCloth, Bonobos, and outdoor-goods merchant Moosejaw. Vendors who wanted to sell products both in stores and online had to deal with two buyers, whose priorities weren’t always aligned.

Store-based merchants focus on profit per item and steady supply, to avoid empty shelves. Online merchants, though, obsess over the accuracy of product listing details, so that web searches turn up the right stuff. To match Amazon’s powerful pricing algorithms, some products would show a different price online than in the store.

Lore’s vision was to staff the online merchandising group with more than 200 recent graduates of elite universities like Princeton, Yale, and Stanford, who would manage a small slice of the business—say, zip-lock bags. These “category specialists” would go through 12 weeks of training, then get unleashed to manage their mini-business as they saw fit.

“As a Category Specialist, you don’t wait years before you call the shots,” promised a recruitment post for the position. “You have full ownership of a multi-million dollar P&L from Day One.”

Lore figured the students, who normally juggled job offers from places like Goldman Sachs and Google, would jump at the opportunity to make an immediate impact. But that impact was largely resentment—“snot-nosed college kids with no skills,” in the words of one employee who worked alongside them. The frustration was mutual, as the green new hires found that their ability to make decisions around product selection and pricing was often limited, according to former employees familiar with the role.

Some longtime Walmart observers downplay the cultural issues, arguing that Walmart is the only retailer with the resources to battle Amazon. “Even on the best teams, you have issues,” says Ken Harris, a managing partner at Cadent Consulting Group, which helps consumer-product companies work with big retailers. “That’s corporate life. Managers figure out ways to navigate.”

For now, it’s up to Walmart’s CEO—who has a foot in both camps—to find a path that the whole team can agree on.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.