Wall Street Has Plans for Newspapers, and They Aren’t Pretty

Wall Street Has Plans for Newspapers, and They Aren’t Pretty

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Warren Buffett always had a soft spot for newspapers. He didn’t just own a lot of them. He described himself as a newspaper addict and fondly recalled delivering them as a teenager. For many years he hosted a newspaper-throwing contest at the annual meeting of his Berkshire Hathaway Inc. conglomerate, challenging anyone to toss a rolled-up paper closer to the front door than he could.

Now he’s getting out of the business. On Jan. 29, Lee Enterprises Inc. announced that it’s buying Berkshire’s 31 daily newspapers and some other publications for $140 million. Buffett set up the sale in a way that allows him to make money from the deal for years to come. Lee will pay Berkshire a 9% annual interest rate on a 25-year loan that it will use partly to pay for the deal and partly to refinance Lee’s other debt and provide cash. Berkshire will also keep the newspapers’ real estate and lease the buildings back to Lee. “Berkshire Hathaway wouldn’t be the company it is without making money in any environment,” says Ken Doctor, a longtime newspaper analyst. Some aspects of the Lee deal, such as the refinancing, could also make it easier for the chain to get through a difficult time for the industry.

Still, the transaction was another disappointing milestone for those who still love and depend on their hometown paper. As private equity and hedge fund investors gained control of the business, Buffett once stood out as someone who believed in the mission of newspapers and had the wealth to invest in a potential turnaround. And he was famous for his patience—in the past, he’s said he’s “reluctant” to sell even subpar businesses. “If one of the richest men on the planet has soured on newspapers, what chance do newspapers have?” wrote Tom Jones, a media writer at the Poynter Institute, a journalism school and research center.

Buffett’s days as a newspaper baron began five decades ago with his acquisition of the Omaha Sun. Over the years, the billionaire investor argued that despite circulation and advertising declines, local newspapers still had some advantages. “If you want to know what’s going on in your town—whether the news is about the mayor or taxes or high school football—there is no substitute for a local newspaper that is doing its job,” he wrote in a shareholder letter released in 2013.

But as readers flocked to the internet, his comments grew increasingly pessimistic. His publications started cutting jobs. In 2012, Berkshire shut down the News & Messenger, based in Manassas, Va. About two years ago, Buffett said he was surprised that the circulation decline hadn’t let up. His business partner, Charlie Munger, suggested their emotions might have clouded their judgment. “The decline was faster than we thought it was going to be, so it was not our finest bit of economic prediction,” Munger said at Berkshire Hathaway’s 2018 annual meeting. “To the extent we miscalculated, we may have done it because we both love newspapers.”

Buffett’s exit wasn’t a total surprise. He was already inching out the door: About 18 months ago, Berkshire asked Lee, which owns the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and more than 40 other dailies, to manage most of its papers. In a statement, Buffett said he was confident that his newspaper empire was in the right hands: “We had zero interest in selling the group to anyone else for one simple reason: We believe that Lee is best positioned to manage through the industry’s challenges.”

Buffett’s former newspapers may soon find themselves under pressure from other investors. Just hours after the deal was announced, MNG Enterprises Inc. disclosed it had bought a 5.9% stake in Lee, becoming its third-largest shareholder, and said it wanted to talk with Lee’s management about the Berkshire deal, among other issues.

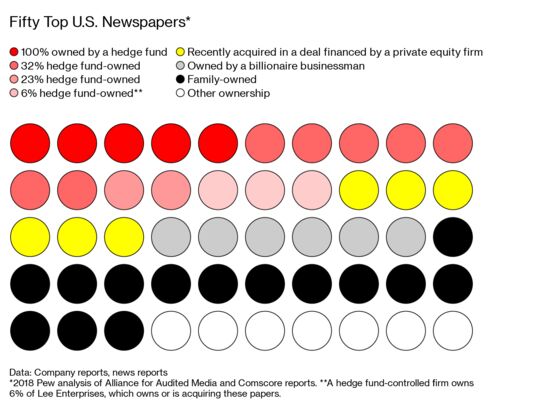

MNG is majority owned by Alden Global Capital, a New York hedge fund, and has a stable of about 50 daily newspapers, including the Denver Post. It’s gained a reputation for making deep cuts to newsrooms, and its journalists once protested outside its New York offices, carrying signs that read “Invest or Sell Now” and “Stop Bleeding Our Newsrooms Dry.” Alden didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Alden’s investment might be the start of a battle for what to do with the Berkshire papers and other Lee assets. Alden could buy a larger stake, gain board seats, and pressure Lee to make further cuts or sell. A year ago, Alden made an unsuccessful takeover bid for the Gannett Co. newspaper chain. Gannett was eventually bought by New Media Investment Group Inc. In November, Alden bought a 32% stake in Tribune Publishing, becoming its largest shareholder. In response, two Tribune journalists published an op-ed in the New York Times in January calling for a new “civic-minded local owner,” saying Alden’s influence could lead to a “ghost version of the Chicago Tribune.”

Alden is one of several Wall Street firms that have gained control over the newspaper industry. Others include Chatham Asset Management LLC, the largest shareholder in McClatchy, publisher of the Charlotte Observer and Miami Herald. New Media Investment Group Inc., which became the largest U.S. newspaper chain after the Gannett merger, is managed and controlled by the private equity firm Fortress Investment Group.

The financial firms’ strategy centers largely around buying other newspapers to boost revenue, then cutting costs by centralizing operations and laying off journalists. But some investors have devised additional strategies to make money. Alden also owns a real estate business that buys and leases newspaper offices and printing plants. Apollo Global Management, a private equity firm, issued a loan to New Media Investment Group to buy Gannett at an 11.5% annual interest rate, an even higher rate than Buffett’s 9% loan to Lee. Fortress collected about $20 million in both 2018 and 2019 for managing New Media Investment Group, according to Doctor, the media analyst. “If you can extract the cash as you’re managing the decline, you can make a lot of money,” he says. “But they do not posit a long-term strategy and turnaround.”

Financial firms have also assumed control of newspapers because they’re willing to shrink them, Doctor says. “The reason you see them in the business and not others is because they do the dirty work of continuing to cut an operation,” he says.

Many newspapers were once owned or controlled by families who stayed in the industry for decades. Buffett had served as a bridge between the old and new generations of owners. He believed in the role of newspapers but could still be gimlet-eyed about the business. “If horses had controlled investment decisions, there would have been no auto industry,” he said in a shareholder letter published in 2015.

Buffett didn’t breathe new life into his newspapers the same way billionaires Jeff Bezos and Patrick Soon-Shiong have since buying the Washington Post and Los Angeles Times, respectively. Buffett’s papers sometimes struggled to embrace change, with his hometown newspaper, the Omaha World-Herald, continuing to publish an afternoon edition until 2016.

Journalists at the World-Herald didn’t want a national chain to own them. Todd Cooper, who leads the paper’s union, says they’d been in touch with Buffett and his deputy Ted Weschler to see if they would be willing to sell if the union could find another buyer. They’d even started to petition local foundations last year to take over the paper. “We just felt that the best fit for journalism and the future of journalism is either single local ownership or ownership groups, or nonprofits, foundations,” Cooper says.

He says he was blindsided by the news about the sale to Lee. Buffett was an investor who had long ties to the industry, yet even he wasn’t able to make it work. “He loved journalism and probably still loves it,” Cooper says. But “he’s totally a numbers guy.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.