Vote-by-Mail Gains Momentum, But It’s Not Fast, Cheap, or Easy

Vote-by-Mail Gains Momentum, But It’s Not Fast, Cheap, or Easy

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The coronavirus outbreak that has forced Americans to retreat to their homes and brought the economy to a standstill also threatens to upend the presidential election. Multiple states have rescheduled their spring primaries as the number of confirmed cases of Covid-19 keeps climbing. Some polling places in states that held primaries on March 17 were hastily closed; at others, workers scrambled to disinfect voting machines and keep people 6 feet apart in line. Voters were encouraged by officials to avoid the health risks of in-person voting entirely—by casting their ballots by mail.

The pandemic has prompted new attempts to expand mail-in voting, a trend that has been slowly building over the last two decades. A bill introduced on March 18 by Oregon Senator Ron Wyden—the first U.S. senator elected in a statewide mail-in election—and Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar would require states to allow mail-in and early voting during a pandemic or natural disaster and would provide funding for the cost of ballots and postage, among other things. The stimulus bill passed by the senate on March 25 includes $400 million for states to allow vote by mail, expand early voting and online registration, and hire more workers, but it doesn’t include a mandate. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi predicted the House would pass the bill on Friday, and said additional bills would be needed.

Even apart from such efforts at the national level, there are signs of an avalanche of mail-in ballots in November. In 2016, the 33 million ballots cast by mail amounted to almost one-fourth of all votes. This year, experts say tens of millions more voters could request mail-in ballots, even without changes in federal or state laws. A dramatic rise in absentee ballot requests could swamp smaller elections boards that have traditionally used a handful of workers to handle mail-in ballots (instead of staffing up or using machines that can scan and verify signatures on envelopes) or have held off opening, certifying, and counting them until polls close. It also could mean that the outcome of the presidential race won’t be known for weeks.

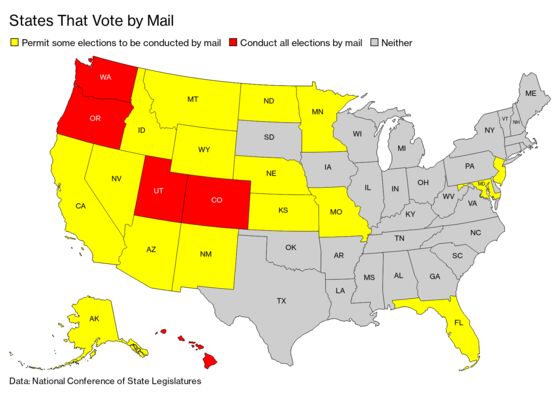

Absentee voting, which began during the Civil War when soldiers were away from home, has become increasingly popular in recent years. Democrats are leading the push to allow vote by mail at the national level, but local officials in red, blue, and purple areas in Western states have also embraced it after seeing it in action. Before the coronavirus crisis, five states were already going to conduct the fall election entirely by mail: Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah, and Washington. Starting in November, California will allow any county to choose an all-mail-in election, supplemented by centralized voting centers. Thirty counties in North Dakota and 11 in Nebraska plan all-mail elections as well.

But those efforts came after years of discussion and preparation. Updating procedures to handle a crush of absentee ballots is a heavy lift. “In our lifetimes, I haven’t seen a bigger challenge to elections officials,” says Thad Kousser, a political science professor at the University of California at San Diego. Kousser says expanding voting by mail offers no clear advantage to either Democrats or Republicans, but a lot depends on how it’s implemented, especially on as wide a scale as he expects this November. Stricter deadlines for absentee requests and receiving mail-in ballots could favor more partisan voters, who tend to cast their votes early.

Michigan and Pennsylvania recently made it easier to request mail-in ballots, but they didn’t update related laws to allow them to be processed before Election Day—which could leave a huge number of uncounted ballots to be dealt with after polls close. Both are swing states that may determine the outcome of the presidential race.

To stave off problems, fast action is required, election experts say. Congress should consider giving states money to buy new equipment, hire staff, and print ballots. State lawmakers need to revisit their absentee voting laws. Local officials must make decisions about polling day staffing. And all those steps take time, which is running out. “It is not at all unfair to characterize right now as the last minute,” says Matt Blaze, an expert on election security at Georgetown University Law Center.

Matthew Weil, director of the Elections Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center, a Washington, D.C., think tank, says it may be easier for some states to shift to an entirely mail-in election, since it’s simpler to mail every voter a ballot than to sort through tens of thousands of requests. Mail-in ballots could be supplemented by voting centers to assist early voters and disabled, elderly, and English-as-a-second-language voters, as well as people who didn’t receive a ballot in the mail.

Local election officials in Maryland, which pushed its primary from late April to June because of the pandemic, have called for an all-mail-in election. In Montgomery County, the number of requests for absentee ballots for the primary is already four or five times the usual rate, says Alysoun McLaughlin, the county’s deputy elections director. In an all-mail-in election, she says, she would just shift the paid volunteers she already has for Election Day into processing and counting ballots. Even then, she’d need more funding to handle the cost of sending out ballots. “There’s no question mailing an absentee ballot out to every registered voter is going to have a cost,” she says. “That’s not cheap, but neither is a public-health emergency.”

Fifteen states don’t allow election workers to process mail-in ballots until Election Day, including four that bar it up until polls close. That slows the reporting of results significantly and requires more workers than are needed in states that allow ballots to be processed but not counted until the election. States also vary as to whether they require ballots be received or just postmarked by Election Day. The latter is more helpful to residents of rural areas and late-deciding voters, but it means results in highly competitive states may not be known for several days.

The delay in reporting results isn’t a problem from the standpoint of conducting an election. But Dale Ho, director of the Voting Rights Project at the ACLU, says it can leave an opening for candidates to cast doubt on the legitimacy of an election they appear to be losing. After the 2018 election, House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy raised questions at a press conference about shifts in vote totals in some California House races that Republicans lost after late-arriving ballots were received, despite the lack of evidence of any malfeasance. In Florida, Senator Rick Scott filed a lawsuit against two counties when his lead narrowed as ballots were counted, arguing that “unethical liberals” were trying to “steal this election.”

The growth of voting by mail will also change how Americans experience election night. A high proportion of absentee ballots may lead to frustration as results aren’t announced for hours or days. “The public has grown accustomed to instant gratification on election night, with results and forecasted winners when polls close or shortly thereafter,” says Ho. If we have to adjust to a slower model, he says, “it’s going to be hard.”

Read more: Big Ideas to Save the Economy, From Bailouts to Super Chapter 11

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.