Virtual Reality Is the Latest Dinner Party Trick

Virtual Reality Is the Latest Dinner Party Trick

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Harry Parr has one of the most dynamic palates on the planet. Half of the London-based food consultants Bompas & Parr, he’s served plasma-cooked bacon, created clouds of vaporized gin and tonic, and dropped banana-flavored confetti in sync to New Year’s Eve fireworks. So it was notable that before he spoke at FoodHack, a conference in Gwangju, South Korea, in June, he made sure to swing by a tiny three-seat stall for a five-course meal called Aerobanquets RMX.

“Meal” is perhaps too strong a word. It was five bites: starting with a mushroom tart with gochugaru (red chile powder) and finishing with a falooda-like dessert of cold corn starch noodles, basil seeds, strawberry ice cream, and rose syrup.

Not that Parr knew.

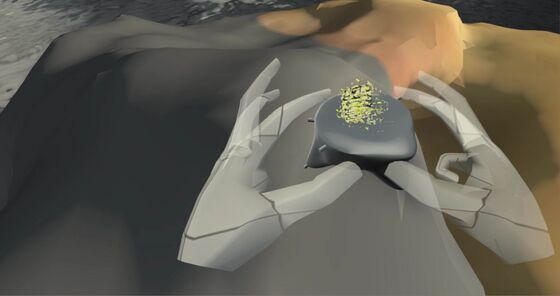

He was blinded by an Oculus virtual-reality headset that kept him in a 3D, interactive world inspired by 1932’s The Futurist Cookbook. Parr saw only virtual sculptures where the food should have been: The tart became a gray asteroidal blob rimmed by an orbiting disc of red crystal debris, for example. After each bite, his virtual world transformed, imbuing a layer of narrative to the meal while playing with the senses. A 2018 Journal of Food Science study found that VR environments affect taste. A VR barn makes cheese taste more pungent, for example, and a VR park bench makes it taste more herbal.

When I tried the experience myself, it reminded me a lot of eating communion wafers as a kid—the hypersensitivity to its placement on the tongue, its texture, the feel of it going down. Frequently, instincts overrode. I clung to a table’s edge or straightened my posture to avoid drowning in a quick-rising milky ocean. Reaching out for an object—a floating accordion, for example—felt utterly natural. I disregarded reality, keenly aware and unaware, the mystery of the food and the surreality of the visuals amplifying each other.

“It’s incredibly powerful,” Parr said afterward. “It’s more than the beginning of something. It works very, very well.” But he wasn’t completely sold. “I don’t think it necessarily transcends yet to what it can do with the medium.”

Small tweaks, he thinks, would bring VR eating closer to a transformative event. Having himself placed diners in all kinds of offbeat situations, he warns it will take some time for the world to ready itself for virtual-reality eating. “We’ve always collectively been a bit put off by experiences like dining in the dark,” he says.

Eating blind is an old stunt, an eye roll. And experiences such as the Oculus tasting at FoodHack, at first glance, can engender a similar response. But whereas turning off the lights is practically free, VR dining is an elaborate affair requiring thousands of dollars in equipment, hundreds of hours in design, and extensive training for helpers.

A certain set of artistic elite think that, for this particular adventure, the effort is worth it.

“I’ve had other VR experiences that were underwhelming, and this was not,” says Sara Devine, director of visitor experience and engagement at the Brooklyn Museum. “The magic of the art is transporting.” Her experience—one of 45 demonstrations in Gwangju—was shared with counterparts from the National Museum of Korea and Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum.

The brains behind Aerobanquets RMX are an unlikely trio. Chintan Pandya, the acclaimed chef at Adda Indian Canteen in Long Island City, N.Y., and Roni Mazumdar, its suave and savvy owner, are at the heart. Through a filmmaker friend, they met Mattia Casalegno, a visual artist from Naples, Italy, who teaches digital arts at Pratt Institute. Casalegno had done a rudimentary version of the dinner at an art exhibit in Shanghai, without restaurant-level food, and he wanted to expand the horizons of the experiment.

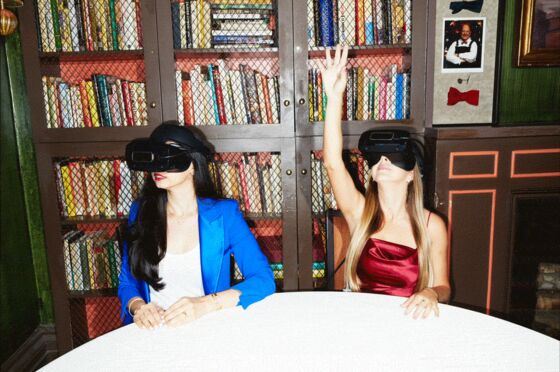

Since March they’ve been quietly offering the VR dining experience to more than 100 people, including musician David Byrne, architect James Ramsey, and Paul Miller, a musician who’s collaborated with the likes of Metallica and Yoko Ono under the stage name DJ Spooky. (To me afterward, Miller calls it “a situation where food and art collide and create a new dimension.”) In early August, Ali Bono, senior manager for special events at the Whitney Museum of American Art, introduced Aerobanquets RMX to tastemakers at New York’s Soho House.

Now the project is entering a new stage with the addition of Mitchell Davis, chief strategy officer for the James Beard Foundation, the body that gives out the awards known as the Oscars of food. The James Beard House, where the luster of the organization wrestles with the dustiness of a 175-year-old West Village town house, will become the virtual dinner’s first publicly accessible home. Former staff offices are being converted into a dining room, and Gail Simmons of Top Chef has recorded a narration for the experience. Opening to the public on Oct. 30, it will feature hourly runs of seven bite-size courses that will cost $125 inclusive of tax and gratuity. Four guests can go at a time.

I meet up with Mazumdar while he’s measuring windows and debating various DIY riggings at the Beard House (what Indians would call jugaar and Americans would call MacGyvering). The giddy futurism of the project is buoyed by his own personal history with tech. He recalls growing up in Kolkata in the late 1980s, before his family got a color television. They made do with plastic color overlays you could buy, like tinted tracing paper, where hopefully a tree would appear on-screen in the green patch. “And even with that,” he says, “we filled rooms and had dozens of people crowding outside to see. Everyone deserves to be a part of the future.”

But the project is also about the food, which is designed to be delicious and texturally interesting. Davis sees it as an heir to molecular gastronomy temples such as El Bulli and wd~50, all the way back to French chemist Hervé This’s experiments in the 1980s. “This is an extension of what Ferran Adrià was doing at El Bulli, playing with memory, perception, and taste,” he says. “It’s digital gastronomy.”

VR is at an inflection point. While consumer VR software investments fell 59% from 2017 to 2018, according to SuperData Research, hardware sales beat forecasts with $3.6 billion in revenue, a 30% year-over-year increase. New standalone wireless headsets such as Oculus Quest are projected to take VR to a $16.3 billion market by 2022. Yet VR pop-ups such as 2019’s Museum of Future Experiences in New York came and went without much fuss. Similar venues Zerospace and the Void are hardly hot-ticket items.

“The problem isn’t price—a VR set is cheaper than a smartphone—the problem is content,” says Jeremy Bailenson, founding director of Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab, who’s been studying VR since 1999. “Gaming and TV work fine without VR. And what else is there for consumers? Not much,” he adds. “But in 2013 we had a $40,000 headset, and there were only a few hundred in the world. Now there are 20 million sets in the U.S.” And as VR gets normalized, it might offer a canny solution to the problems that technology has brought to dining, such as the phenomenon of caring more about posting your dinner to Instagram than enjoying the actual meal itself.

Ironically, immersion in a virtual world can restore emotional presence and focus. Having observed dozens of virtual meals and participated in two, there’s always a reverse Pinocchio moment: users staring at how unreal their hands have become, as rendered by infrared sensors. The art itself is retro, reminiscent of the 1992 film The Lawnmower Man or the Mind’s Eye videotape series from the ’90s—evocative, Casalegno says, of a time when the internet was more about cyberspace than data mining.

Other endeavors using new visual tech have settled on simpler augmented reality. City Social in London overlays animations on cocktails when viewed through your phone (like Pokémon Go). Tree by Naked in Tokyo utilizes multisurface projection art, as does the $2,000-a-head Sublimotion dinner in Ibiza, billed as “the greatest gastronomic show in the world” with its laser light show, scored music, and transportive moments via Samsung Gear headsets. Yet all of these rely more on theatricality than on a mind’s-eye sensory surprise.

After his Aerobanquets RMX meal in Gwangju, Takuji Narumi, a lecturer on sensory experience at the University of Tokyo, called it “pure taste, without expectation. It’s quite different from what we have called dining.”

And not just because the eating itself is cumbersome, involving a two-handed grasp of a strangely shaped platform for the food, which is raised and tilted awkwardly and hopefully into the mouth. Kathleen Box, a vice president for marketing and events at Prada SpA, spilled her food down her front during a dinner this spring. But there’s also a thrill of prototyping, of concept art—a wobbly tightrope stretched between the anchors of creativity and progress.

Ultimately, the project’s fate will be decided by everyday diners. A custodian who did it, Youngah Choi, 60, spent much of the experience freaking out. “It was terrifying,” she said, “but worth it for that dessert.” Okhee Kwon, a 67-year-old housewife who tested it out to make sure her husband would like it, was rapturous.

“I want to live there. It’s the world of imagination,” she said. “That’s where all the best things are.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Justin Ocean at jocean1@bloomberg.net, Chris Rovzar

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.