Billionaires Are Begging to Buy This Art. Too Bad

Billionaires Are Begging To Buy This Art. Too Bad

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Jeff Koons, Gerhard Richter, and David Hockney are household names with prices to match. The artist Vija Celmins commands similar prices from a lofty collector base; Henry Kravis, J. Tomilson Hill, and Mitchell and Emily Rales own work by Celmins, as do corporate collections such as those of JPMorgan Chase & Co. and the Cartier Foundation. But in contrast with her peers, you might see her name and ask, “Who?”

“I’m not speaking in any kind of pejorative way, but I’ve always thought of Vija as a niche artist,” says Laurence Shopmaker, co-founder of Senior & Shopmaker Gallery in New York, which will exhibit a group of Celmins’s prints from Sept. 12 to Nov. 2.

That might change after the Met Breuer opens its fall season on Sept. 24 with a 120-object retrospective of her work, the first in more than 25 years. The show, which features many of Celmins’s hyperrealistic drawings, was initially on view in San Francisco and Toronto, where it was met with uniformly positive acclaim. (“Why is this genius artist only now getting a show worthy of her art?” gushed the Washington Post.) Its reception in New York is expected to be similarly rapturous.

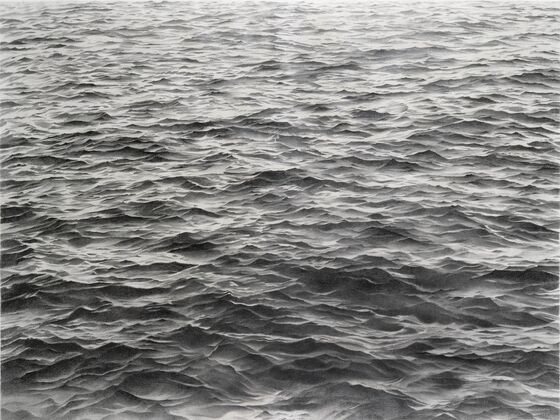

“She’s always been recognized as a fantastic artist,” says Met curator Ian Alteveer, “someone curators and critics and artists and a certain group of collectors have loved.” Her paintings sell for upwards of $5 million and drawings for about $1 million, placing Celmins, who’s now 80, at the very top of the contemporary art world and the top of the art market generally. In November one of her drawings, Untitled (Long Ocean #5), from 1972 will come to auction at Christie’s, carrying a high estimate of $2 million.

Her success flies in the face of conventional wisdom about the art business, which holds that to create a sustainable market, hypersuccessful artists need the trifecta of institutional, art dealer, and auction house support, all of which play off one another. Instead, Celmins’s career offers a rare example of an artist’s prices growing even as her process challenges all three branches of the art world.

Because of Celmins’s time-intensive practices, her output is very low. For a gallery and collectors, “the problem is getting the work,” says Renee McKee. “She was also not that interested in working on museum shows. They always interrupted her work.” Along with her husband, David, McKee spent more than 30 years building Celmins’s market through their New York gallery. On the secondary market, where the artist and her dealers have less control over what comes up for sale, Celmins’s art is nearly impossible to buy—again, a volume issue. Just two noneditioned works, including a 19-inch graphite-on-paper depiction of the night sky that sold for $2.4 million, have come up for sale in the past 12 months.

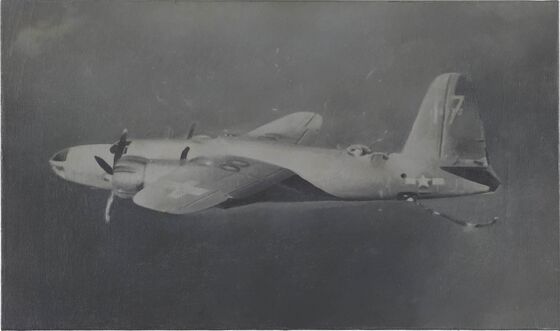

The simplest explanation for Celmins’s success is the art itself. “It’s super detail-oriented, and it’s super precise,” says the Met’s Alteveer. After beginning her career painting realistic, life-size depictions of the objects in her studio, Celmins moved to painting World War II planes. Then, “in 1968 she decides to leave paint altogether and for the next 10 years only used graphite,” Alteveer says.

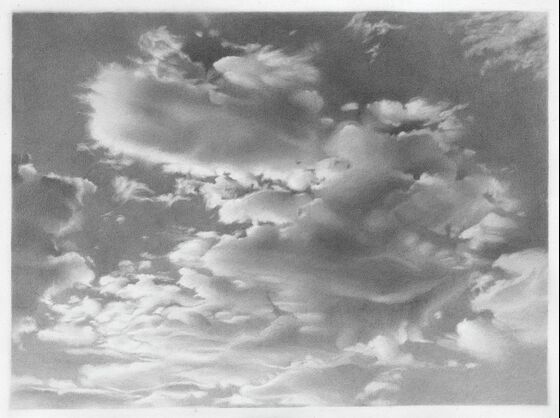

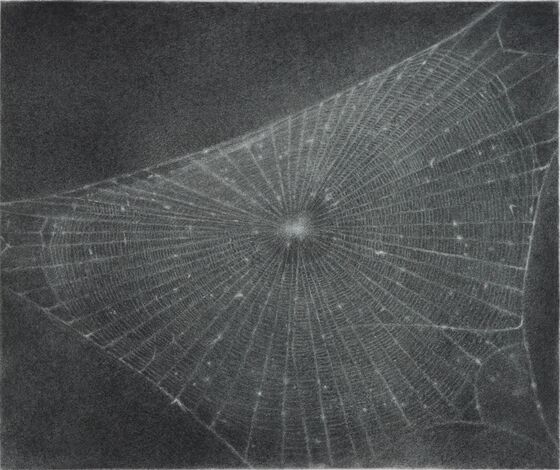

Soon after her switch, she began to make her ocean series, ethereal and spectacularly detailed drawings of photographs of the water’s surface. This work became arguably her most famous. “Carefully, sometimes over three months, she would redescribe [on paper] what she sees in the photo,” Alteveer says. She never used an eraser with this series; if she erred, she tossed out the piece and began again. Along with the oceans was a series of desert drawings and another of constellations. In the 1980s, Celmins began to paint again—the oceans and deserts were rendered in oil—and she began a series of the night sky; the paintings were often created with as many as 20 layers.

“It’s very labor-intensive,” McKee says, having seen the artist at work. “She paints, then scrapes it off, then paints it again. It’s layer upon layer until she’s happy with it.”

“She’s actually quite quick,” she continues. “She just doesn’t like what she comes up with, and then she has to start all over again.” Thus, Celmins’s collectors often have to wait years before they have a chance to acquire an original work. (Her current gallery, Matthew Marks, declined to comment on the existence of a waiting list.)

“Her collector base grew from the initial people who were interested to other people who saw her museum shows and wanted a work in their collection,” says McKee—because that’s how the trifecta is supposed to work. But even as demand built, Celmins resisted price hikes. “It was always as difficult to get her to release her work as it was to get her to raise her prices. That’s Vija.”

Eventually, though, prices did rise. “We tried not to sell to speculators or people who really didn’t understand who they were buying,” McKee says. “They had to be serious clients.” Today that clientele, by dint of cost, is almost exclusively very wealthy collectors. The McKees closed their gallery in 2015, and Celmins went to Marks, at which point her prices continued to soar.

Not that it matters much to the artist, McKee says, “but she’s not unaware of it.” Instead, Celmins has “tried to keep her sense of integrity and belief in the art that she’s creating,” McKee says. The marketing and selling are the purview of her dealers.

“Of course there was a lot of advocacy” on her behalf, she says. “Everyone who came into the gallery, all of the art fairs we did, we’d talk about her. [A market] doesn’t happen by itself.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Chris Rovzar at crovzar@bloomberg.net, Justin Ocean

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.