Veterans Pay High Price as Lenders Push Cash-Out Home Loans

Veterans Pay High Price as Lenders Push Cash-Out Home Loans

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Eric Kandell is making his pitch to veterans. Wearing a red T-shirt, with the words “Low VA Rates” emblazoned across his chest, he looks fit and muscular, as if he had stepped off an Army base himself. In this YouTube video and others, he tells current and former service members how they can take tens of thousands of dollars in cash out of their homes. They can pay off credit cards, remodel a kitchen, install a swimming pool, or travel to Las Vegas. “Do whatever you want,” he tells them. “Imagine your home is like an ATM.”

Kandell is targeting borrowers from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs mortgage program. He’s the 43-year-old president of a company whose very name is a come-on: Low VA Rates LLC. It’s among the lesser-known financial outfits dominating the business of selling cash-out VA mortgage refinancing, which totaled $41 billion worth of new loans over the past year.

This boom is alarming federal regulators. Lenders, who can charge thousands of dollars in fees, are encouraging veterans to extract as much as 100 percent of their home equity. Many of the borrowers have poor credit and low incomes, and they could soon find themselves deep underwater. Multiple refinancings helped spark the 2008 financial collapse. In a recent Federal Register notice, the VA itself says financial companies are reviving “subprime lending under a new name.”

Lenders say they’re providing a valuable service to cash-strapped veterans. Many borrowers use the money to pay off high-rate credit cards, medical bills, or home repairs. “These guys were asked to put their life on the line, and we trusted them to make the right decision in defending our freedom,” Kandell says in an interview. “Yet we want to dictate what they do with their finances. I don’t find that to be American.”

Founded in 1944, the VA loan program began as a way to offer a hand up to returning World War II service members. In the event of a default, the government guarantees 25 percent of the loan; the lender is responsible for the rest. Government-owned Ginnie Mae backs bonds based on these loans, which are packaged and sold to investors, such as pension and mutual funds.

The loans have helped generations of veterans buy homes. But refinancings can be a costly way to free up money. In a cash-out transaction, borrowers get a new loan for more than they owe on their current mortgage. A VA borrower must pay as much as 3.3 percent of the loan amount to the federal government as a fee that offsets defaults. (Historically, default rates have been relatively low.) Closing costs and lender fees typically add 1 to 3 percentage points more, according to David Battany, executive vice president for capital markets at San Diego-based Guild Mortgage. Lenders say many borrowers take the option of paying a higher mortgage rate, rather than upfront fees.

A veteran with a $250,000 home loan who pulls out $20,000 in cash can easily end up paying more than $14,000 in fees, Battany says. “Customers rightfully complain when they have a $2 ATM charge,” he says. “This is, in effect, a $70 charge on a $100 withdrawal.” Even if customers pay off a high-rate credit card, they’ve extended the term of their debt for decades. And, unlike with credit card debt, if they fail to make mortgage payments, they can then lose their homes. The VA estimates that more than half of borrowers who take cash out of their home are vulnerable to predatory lending behavior, which includes poor disclosure or making loans with little benefit to the borrower.

Larry Speights, a veteran who spent 24 years in the Army, says he called a lender named NewDay USA after watching one of its TV commercials, pulling out $20,000 from his VA mortgage in 2017 to pay off credit cards. The refinancing required more than $14,000 in closing costs and fees, he says, and NewDay called him six months later in 2018 to refinance again, offering a lower rate that he says should have been given to him in the first place. He took the loan. “I know people got to make money, but I think they should be more cautious when messing with veterans,” says Speights, who lives in Waleska, Ga. “We’ve already been through a lot.”

Citing customer privacy, NewDay declined to comment on individual borrowers. Robert Posner, NewDay’s chief executive officer, says borrowers often lower their overall debt payment by hundreds of dollars a month, and may improve their credit scores, by putting the proceeds of a refinancing toward credit cards and other high-interest debt. “I’m not saying, at the end of the day, that a VA cash-out loan is perfect,” Posner says. “But it’s a heck of a lot better than paying 21 to 23 percent on a credit card. This is cheap money.”

For more than a year, Ginnie Mae has been fighting what it calls “churning”—the practice of repeatedly pushing veterans into unnecessary refinancing. Ginnie Mae temporarily suspended VA loans from NewDay and others from being included in some of the pools of mortgages for bonds it guarantees. Posner says NewDay will refinance only if it provides a cost savings to the veteran and will do so only once. “NewDay USA does not churn and has never churned,” he says.

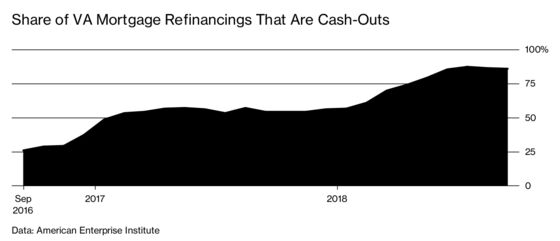

Ginnie Mae now requires borrowers to wait at least six months between deals, and Congress started mandating that refinances provide an “actual benefit” to military families by, for instance, lowering rates. But, after lobbying from lenders, Congress left a loophole: Cash-out refinances required no such benefit, other than the cash itself. Cash-outs accounted for 86 percent of VA refinancing in September, up from only about 30 percent two years earlier, according to an analysis of federal data from the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. As interest rates rise, “lenders and brokers are increasingly desperate for business because the refinancing wave has run its course,” says Michael Bright, Ginnie Mae’s chief operating officer. “What’s left? Cash-out refinancings, where the guardrails are not tight.”

Even after the crackdown, the proportion of borrowers who took cash out of their mortgage and then refinanced again in six to eight months rose over the past year, to 7 percent from 6 percent, according to data compiled by Ginnie Mae. It’s now considering further restrictions on refinancing and kicking more lenders out of some pools of mortgages it backs. Along with the effect on veterans, government regulators fear that frequent refinancing could turn off bond investors looking for stable income payments, ultimately raising interest rates for all consumers. Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Pacific Investment Management Co., and other big bond investors recently complained that high VA loan prepayments might lead them to scale back purchases.

In December, the VA proposed subjecting cash-out to the “actual benefit” standard. Kandell, the Low VA Rates president, said the rules wouldn’t slow down business much, since nearly all deals could meet that condition.

Meanwhile, companies such as NewDay keep pitching cash-out refis. The lender keeps a high profile. Former Baltimore Orioles star shortstop Cal Ripken Jr. once worked as a pitchman. In one online video featuring a rippling American flag, Ripken says he’s proud to represent the Fulton, Md.-based lender, a hometown institution. “As a veteran, you’ve earned the right to apply for a loan that lets you borrow up to 100 percent of your home’s value,” he says. Through a spokesman, Ripken says his relationship with NewDay ended.

Tom Lynch, a retired U.S. Navy rear admiral, gushes in his own video spot for NewDay: “You gave 100 percent to your country. Let NewDay give 100 percent to you!” In another, veterans cheer: “Thank you, Admiral!”

Another major VA refinancer, Illinois-based Federal Savings Bank, sent a flyer to Frank Preciado, an Iraq War veteran in Phoenix. “Expiration notice,” it reads. “Our review has indicated that the waiting period has been marked as expired … you have not accessed your equity reserves of $4,068.34.”

Preciado says the notice seemed designed to appear as if it were from the federal government. The bank uses an eagle as its symbol. The company says the notice “clearly identified that it came from Federal Savings Bank.” Says Preciado, who works as a mortgage broker: “Federal Savings Bank knows better, and those practices need to stop.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: John Hechinger at jhechinger@bloomberg.net, Pat Regnier

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.