Venezuela’s Latest Problem Is There Are Now Too Many Dollars

Venezuela’s Latest Problem Is There Are Now Too Many Dollars

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- U.S. dollars are everywhere in Venezuela, and suddenly that’s a problem.

The greenback is steadily gaining currency in this inflation-wracked country, where a single dollar buys about 60,000 bolívares on the black market. That’s creating challenges for local businesses, because Venezuelan banks are barred from offering foreign currency accounts.

For safekeeping, an insurance saleswoman in the western town of San Cristóbal tapes stacks of dollars from clients to the inside of a toilet tank in her office bathroom. A general contractor, unable to wire cash to his accounts in the U.S., flew his elderly mother and wife from Caracas to Miami with $9,900 of cash each, just under the limit required for reporting money to U.S. customs authorities.

“This is money earned through legal means, yet in a currency that exists entirely outside the country’s constitutional order. This isn’t money laundering,” says Luis Godoy, a former deputy chief of the judicial police who now works as a security consultant. “You have to wonder how many people right now have money stacked inside their homes like Pablo Escobar.”

The collapse of the bolívar, which shed 99% of its value against the dollar in 2019, mirrors that of the Venezuelan economy, which has endured 21 consecutive quarters of decline. The crisis has been aggravated by international sanctions that prohibit exports of oil to the U.S. and cut access to external financing. While inflation has abated somewhat, largely through severe restrictions on lending, it remains the highest in the world, at an estimated annual rate of 6,567%, according to Bloomberg’s Café Con Leche Index. A year ago, a cup of coffee cost 450 bolívares; at the end of last month it was 30,000 bolívares.

Increasingly, the bolívar is used mostly to pay for a few subsidized goods, such as subway tickets and gasoline, that cost less than a penny a tank in the former petrostate. The dollar has crept in for almost everything else. Hairstylists and window washers quote their prices in dollars. Juice and hot-dog stands in Caracas are adorned with signs advertising that they accept payment in dollars or via Zelle, the U.S. peer-to-peer payment system.

José Gómez runs a corner store in a working-class Caracas neighborhood that’s stocked with Brazilian sweets and liquor. About 70% of his sales are in dollars; a bottle of Buchanan’s whisky runs $30. “We don’t know for how long the tax authorities will ignore us,” he says.

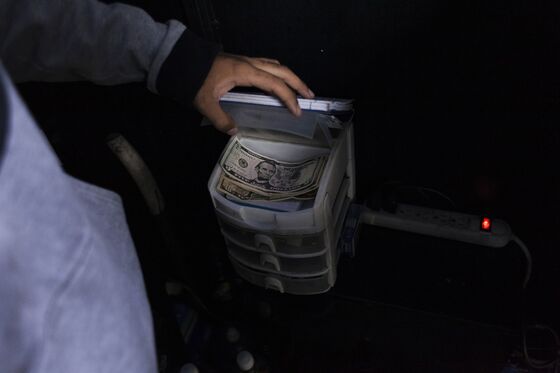

Juan Carlos, who asked that his last name be withheld for security reasons, owns a shop in the Chacao district of Caracas that sells imported luxuries such as Nutella and gluten-free flour. He has about $3,000 in his register on any given day. He pays suppliers in dollars and takes his profits home at the end of the day. “We’ve turned back to the 1920s, to keeping cash under our mattresses,” he says.

Banks in Venezuela can’t offer dollar checking or savings accounts. Several banks allow clients to stash their greenbacks in safe deposit boxes, and some charge a steep 2% fee on withdrawals. Venezuela’s bank regulator, Sudeban, declined to comment.

The dollar’s ascendance has stoked fears about another wave of violent crime like the one that began in the late 1990s, when gun-toting bandits on motorcycles preyed on drivers waiting at red lights. The number of so-called express kidnappings—daylong abductions for ransom—also skyrocketed.

In December, Andrés Gutierrez was robbed at gunpoint outside his home in the Caracas neighborhood of Macaracuay as he was coming back from a party. “He took my phone and was pointing his gun at me as I lay on the sidewalk. He told me to close my eyes if I didn’t want to die,” Gutierrez says. He later managed to make a deal, offering the pair of thieves $100 to get back his Phone. “If I hadn’t had dollars, they would have never given it back,” Gutierrez says. “I don’t think they would have accepted a bolívar transfer.”

While crime figures aren’t readily available, theft and kidnappings are believed to have decreased in recent years as the bolívar lost value, ammunition increased in price, and the rich—and poorest—left Venezuela in an exodus of 5 million people. With more dollars in circulation, there’s once again something valuable to steal. “Any moment, we will see crime blow up, because we’re facing a huge problem with how to move cash. It’s chaos,” says Jorge Barrios, who owns Caracas-based Gallery Security. “Stores and homes are becoming cash deposits.”

While President Nicolás Maduro railed against the idea of officially swapping the bolívars for the U.S. dollar last year, equating it with a surrender of sovereignty, he thanked God for greenbacks in a November interview, crediting their increased use with an economic recovery and resurgence of production.

If the regime were to follow in the footsteps of countries such as El Salvador and Ecuador that have formally adopted the dollar as their currency, Venezuelans would turn in their bolívar, which would be destroyed, exchanging them for dollars from the government’s remaining reserves at a determined exchange rate. That would go a long way toward ending hyperinflation and restoring incentives to save and invest.

For now, though, the dollar remains in a dangerous gray area: heralded by the president, yet mostly outside the rule of law. “The government has turned a blind eye to this,” says Gómez, the store owner. “Now we’re living with ropes around our necks, like fugitives.” —With Alex Vasquez

Read more: Life in Caracas—Postcards From a Land in Total Disarray

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stephen Merelman at smerelman@bloomberg.net, Cristina Lindblad

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.