The Undersea Cable Market Is Booming Again, This Time Funded by Big Tech

The Undersea Cable Market Is Booming Again, This Time Funded by Big Tech

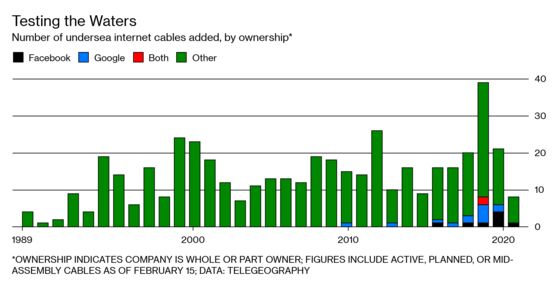

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- During the 1990s dot-com boom, phone companies spent more than $20 billion laying undersea fiber-optic cables from New York to London, through the Mediterranean, across the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and beyond. They were preparing for an expected explosion in internet traffic, but when the bubble burst at the turn of the millennium, operators unloaded cables for pennies on the dollar. That fiasco discouraged investment in the industry for the better part of a decade. Now, with data traffic surging—videos on Netflix and YouTube, songs from Spotify and Pandora, innumerable posts on Twitter and Facebook—the excess capacity has been absorbed, sparking another investment boom, with more cable laid in 2018 than in any year in almost two decades. The industry “is as strong as it’s been since they all went bust,” says Tim Stronge, vice president for research at telecom consultancy TeleGeography. “There’s an awful lot of cable going in.”

The leaders of today’s boom are two of the biggest generators of data traffic: Google and Facebook. Internet companies are behind about four-fifths of transatlantic cable investment planned for 2018-20, up from less than 20 percent in the three years through 2017, according to TeleGeography. Google has become “by far the biggest investor” in submarine cables, even taking full ownership of two of them—a reflection of the vast amounts of data the company transmits, says Mike Conradi, a lawyer at DLA Piper in London who’s been working on undersea fiber deals since 1999. Content companies “can make or break these cables.”

The digital giants, also including Microsoft Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., have reshaped the way the industry works. Before the newcomers arrived, phone companies typically formed single-purpose businesses to build cables, primarily from England to the U.S., which mostly connected old-fashioned voice calls and a smattering of data traffic. Today the internet companies can dictate where the cables land, bringing them out of the water close to their data centers. And they can tweak the structure of the lines, which typically run about $200 million for a transatlantic link, without waiting for partners to approve changes. “There are geographical pinch points in a global network—based on the reality of populations, oceans, and geography—that can’t be avoided, just planned and engineered around,” says Jayne Stowell, a leader of Google’s cable team.

New regional players are also entering the business, particularly from China. Huawei Technologies Co. has a joint venture with British company Global Marine Systems, though concerns about the Chinese government’s influence over Huawei have kept it from being hired to lay transatlantic links. But the company has worked on major projects including a 9,000-mile line that connects Britain to South Africa and 12 other countries along the way, and a 3,700-mile route from Cameroon to Brazil. Facebook and Amazon Web Services are teaming up with China Mobile to link San Francisco to Hong Kong and Singapore. A group of companies from South Africa, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia are working on a line connecting those countries.

Technological advances, climate change, and shifting political considerations are opening routes, including previously inaccessible passages through the Arctic. Those links could shave a few milliseconds off the time it takes to connect London with Tokyo or Shanghai. That can mean the difference between profit and loss in computer-assisted stock trading, and it could accelerate new applications such as driverless vehicles that require ultrafast communication.

Speed isn’t always the primary concern: At least two new cables will snake around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, adding a bit of time to communications but avoiding a bottleneck at the Suez Canal. More than a dozen lines crowd the seabed there, making it a potential target for terrorists seeking to shut down global communications but also creating the risk that a single dropped anchor could take out a big chunk of capacity.

Perhaps the most plausible of the Arctic projects is backed by the Finnish government-owned company Cinia Group Oy. The plan is to connect Scandinavia with Japan via an 11,000-mile, $600 million cable. Skeptics say the line risks being shut down or tapped by Russia, through whose waters it will inevitably pass, and that it might take months to repair a breakage when the ocean is icebound during winter. Jukka-Pekka Joensuu, an adviser to Cinia, says those fears are overblown and that the project’s leaders will make no compromises on security. “Bluntly, it has to be as cybersecure to Americans as it is to the Russians, Chinese, Japanese, or Europeans,” Joensuu says.

Given that the companies building the cables today are the same ones that will use most of their capacity, there’s less risk of a collapse than there was two decades ago. But an unforeseen technology that multiplies the volume of data cables can carry—not unheard of in the industry—could put many investments underwater again. And even if history isn’t repeated on transatlantic routes, the danger could simply be transferred south, says Nigel Bayliff, chief executive officer of Aqua Comms, a cable-laying operation that works with Silicon Valley companies. At least a half-dozen routes from the U.S. to Brazil have recently been completed, “a massive overbuild,” he says. “There is nowhere near the volume to justify even two of the six.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.