Uber and Lyft Are Spending Millions on Driver Bonuses to End Shortage

Uber and Lyft Are Spending Millions on Driver Bonuses to End Shortage

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Misty Huffman has driven sporadically for Uber in El Paso over the past year, even as Covid-19 surged and many of the ride-hailing app’s regular customers stayed away. One recent Friday she opened the app and was surprised to see large numbers of people requesting rides at restaurants, bars, and other nightspots downtown. “The whole city was lit up, end to end,” she says.

Huffman made $1,000 that weekend, a better rate of pay than she gets from her day job as a respiratory therapist. The increase in riders was a factor, but more than a third of the money came directly from Uber in bonuses. “The incentives are crazy,” she says.

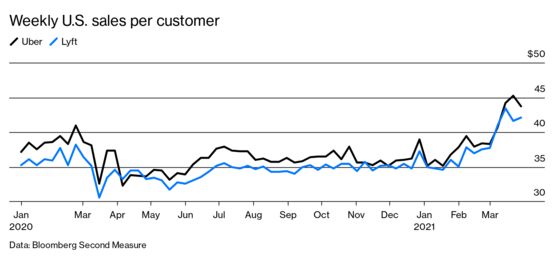

Ride-hailing collapsed a year ago when the pandemic set in. Volume for Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft Inc. dropped more than two-thirds in a single week last March, according to data from Bloomberg Second Measure LLC, which analyzes consumer spending. A gradual increase this year accelerated last month, as vaccination rates climbed and people returned to their normal activities. Lyft’s sales for the week ended March 29 were 80% higher than in the first week of the year, and Uber’s climbed 76% in the same period, according to Second Measure. “Demand is rising rapidly with every vaccination,” says Lyft President John Zimmer. “It’s almost like the reverse of the pandemic.”

Drivers are proving less enthusiastic about hitting the road again than riders. Safety concerns and the lack of steady work led many to look to food delivery and other fields, and it’s unclear whether the availability of vaccines will bring them back.

This reluctance has meant longer wait times, which threaten to undermine the appeal of ride-hailing to consumers, who’ve been trained to expect near-instant gratification. “In most, if not all, of our major cities, riders are coming back faster than drivers,” says Carrol Chang, who heads driver operations for Uber in the U.S. and Canada.

To sweeten the deal, Uber and Lyft are resorting to generous cash bonuses for driving or referring new drivers, a once-common tactic they’d largely phased out because it led to heavy financial losses. Uber said in April it would earmark an additional $250 million to pay incentives to drivers in the near team. Lyft is also offering bonuses but hasn’t announced a total amount. Uber says drivers in Chicago, Philadelphia, and several other cities are now making more than twice the hourly minimum wage before the new incentives; according to Lyft, its drivers in Denver, Philadelphia, Phoenix, and San Diego are bringing in at least $40 an hour. Those rates include the time when drivers have their app turned on waiting for fares.

“It definitely reminds me of the good old days,” says Harry Campbell, founder of therideshareguy.com, a website that provides resources for gig economy workers.

Lyft and Uber, which are slated to report quarterly earnings in early May, declined to discuss their plans for future programs or the size of their driver pools, citing financial disclosure regulations.

The incentives won’t last. Both companies have promised investors they’ll turn profits this year (before accounting for interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization), and they’ve reduced headcount and other costs to get there. Until normal activity returns, they say, the programs are necessary to recruit drivers. Pedro Palandrani, an analyst at Global X, an exchange-traded fund firm, says the near-term financial hit will make ride-hailing work well at a critical period. “They are going to see a good return on this investment,” he says.

Not every driver is open to being romanced. One driver in Oakland, Calif., who asked to be identified only by his first name, Gabe, said he’ll stay off the road until at least September, when his $300 in weekly unemployment benefits expire.

The brutal nature of the job and years of built-up tension have also soured many of the companies’ workers. “I don’t trust them. They entice us with bonuses, and they always find a way to weasel out and not pay us,” Gabe says, adding that he’s been unable to collect on past incentive programs. This complaint has come up before, as when some drivers realized they weren’t getting the bonuses Uber had promised them for using electric vehicles. When Bloomberg Green discovered the error, Uber attributed it to a technical glitch and retroactively paid the drivers, along with an additional 10%.

“Drivers have a lot of choices—it’s our job to earn their trust every day and make driving with Uber worth their while,” says Uber spokesman Matt Wing.

But some want to cash in when the money is good. “When I turn on my app now, it’s bam, bam, bam! Passenger count is way up, and I can’t even turn off my app to go to the bathroom sometimes,” says Jack Hamilton, who’s been driving for Uber and Lyft in Atlanta for about seven months. “It’s never been this good.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.