The U.S. Steel Sector Would Be Booming Even Without Trump’s Tariffs

The U.S. Steel Sector Would Be Booming Even Without Trump’s Tariffs

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When President Donald Trump slapped 25% tariffs on foreign-made steel in early 2018, roiling markets and rankling allies, American steel was hurting. Employment numbers in the industry had hit a new low the previous year, annual mill usage was hovering near just 70% of capacity, and cheaper imports were flooding the U.S. “We must protect our country and our workers. Our steel industry is in bad shape,” Trump tweeted in March 2018. “IF YOU DON’T HAVE STEEL, YOU DON’T HAVE A COUNTRY!”

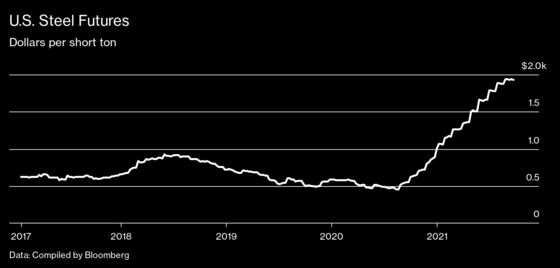

Three and a half years later, the sector is in a very different place. America’s steel mills have been producing at their highest levels since the Great Recession, and their owners are on track to book their fattest profits ever, thanks to record high prices. As the global economy bounces back from its pandemic lows, sales of steel-made products ranging from paper clips to cars to dishwashers are through the roof. Wall Street analysts predict that 120-year-old U.S. Steel Corp. will earn $5.5 billion in 2021 by one closely watched measure, more than it did in all of Trump’s presidency. Nucor Corp., the biggest North American producer, could earn $9.3 billion—more than double its previous best year and on pace to be a larger annual haul than either Nike Inc. or Netflix Inc. is expected to book.

That reversal of fortunes has the Biden administration discussing internally if now is the right time to begin paring back Trump’s tariffs, which critics—namely heavy consumers of steel, including makers of autos and home appliances—say are no longer needed to bolster a domestic industry that would still log robust profits, even without import protections.

The White House is said to be weighing removing the duties, at least those on shipments from the European Union, according to a person who is familiar with the situation but is not authorized to discuss the deliberations publicly. Instead, it is considering implementing a tariff rate quota system under which any imports over a certain level get taxed. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo and U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai are meeting with their European counterparts this week to discuss the matter. Administration officials hope to arrive at a decision by the end of the year.

President Joe Biden wants to mend fences with Europe and revitalize the alliance to jointly curb China’s might. There’s also a growing feeling inside the White House that U.S. steelmakers are getting greedy, according to a person familiar with the administration’s thinking.

At the same time, Biden, who hails from Pennsylvania and has painted himself as an advocate for workers in Rust Belt industries such as steel, wants to make good on his campaign promise to create more union jobs. There’s also the cold political truth that steel workers, even in their dwindling numbers, have a great impact in important swing states, including Ohio and Pennsylvania.

The steel industry has raised the alarm that the removal of the tariffs on European steel could result in a flood of what it dubs “high-carbon” imports from blast furnace mills across the Atlantic that are more polluting than U.S. mini mills. They also warn that producers in China and elsewhere could route U.S.-bound shipments through the EU to evade duties.

Tom Conway, who heads the United Steelworkers (USW), has indicated he would countenance removing the EU tariffs provided there was a monitoring mechanism in place to ensure steelmakers in other countries did not exploit loopholes. “I’m one that would take a quota,” he said in an interview in June.

That gives Biden some wiggle room. And even if the tariffs are revoked, the USW can look forward to billions of dollars in new spending on bridges, ports, and other steel-intensive projects once Congress signs off on an infrastructure plan.

Pushing to remove the tariffs are U.S. manufacturers, which have reported a hard time getting metal. In a briefing paper released in March, a group of 37 U.S. trade groups, ranging from the American Petroleum Institute to the Beer Institute, advocated for the removal of duties. Lead times for steel delivery had pushed out to as long as 16 weeks, the group said, compared with four to six weeks in late 2020.

It’s gotten worse since. This summer, some domestic steel mills were booked so far out that they started turning away orders. Foreign steel, less able to compete on price because of the tariffs, isn’t picking up the slack: Through July imports totaled 14.1 million tons, data show, the second-lowest volume for the period in a decade.

Steelcase Inc., a maker of office furniture, has already raised prices twice this year to offset the rising cost of the metal. Then last week, the company announced an “unprecedented” third hike. As Chief Executive Officer James Keane put it on a recent earnings call: “Steel inflation has been extraordinary.” —With Jenny Leonard

Read next: Inflation Guy Michael Ashton Sees More on the Way as Investors Worry

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.