China’s Commodities Binge Makes America’s Future More Expensive

China’s Commodities Binge Makes America’s Future More Expensive

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Fresh from passing a $1.9 trillion stimulus bill, U.S. President Joe Biden on Wednesday turned his attention to a similarly vast package of investment in infrastructure, and that means the U.S. is going to need more commodities. There’s just one problem: China.

America requires steel, cement, and tarmacadam for roads and bridges, and cobalt, lithium, and rare earths for batteries. Above all, it needs copper—and lots of it. Copper will go into the electric vehicles that President Biden has said he’ll buy for the government fleet, in the charging stations to power them, and in the cables connecting new wind turbines and solar farms to the grid. But when it comes to these commodities—and copper in particular—Washington is one step behind Beijing.

China was the first place the coronavirus struck, but it was also the first country in the world to start recovering from the pandemic. As the rest of the world went into lockdown and commodity prices plunged in March and April 2020, China went on a buying spree. Chinese manufacturers, traders, and even the government approached the global commodity markets much as a shopaholic might approach a fire sale.

“They bought a lot last year, and I don’t believe it was solely for their industrial needs,” says David Lilley, a veteran copper trader who is managing director of U.K.-based Drakewood Capital Management. “It was also about building the strategic reserves of copper needed for their plans.”

China imported 6.7 million tons of unwrought copper last year, a third more than the previous year and a full 1.4 million tons more than the previous annual record. (The year-on-year increase, alone, is equivalent in scale to the entire annual copper consumption of the U.S.) Traders and analysts reckon that China’s powerful and secretive State Reserve Bureau bought somewhere from 300,000 to 500,000 tons of copper during the price slump.

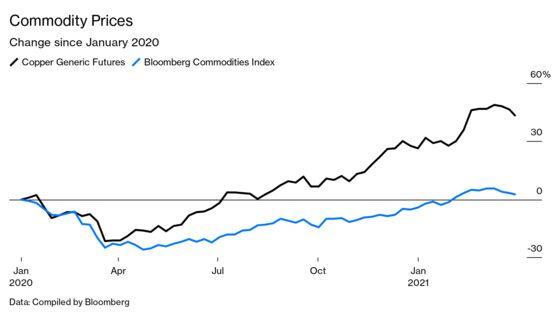

That already looks to have been a smart trade. In part thanks to China’s buying, copper prices have doubled from their March 2020 nadir to current levels around $9,000 a ton. But some reckon copper and other commodities have much further to run. The combination of rebounding global growth and government largesse has bulls fired up. Wall Street analysts enthuse about a new commodities “supercycle”—a period of above-trend prices driven by a structural shift in demand, comparable to the China-led boom of the 2000s or the period of global growth following World War II.

Oil skeptics say faster adoption of electric vehicles will inevitably mean less demand for crude. But for metals like copper, there’s less disagreement. Normally cautious traders are trying to outdo one another in their predictions for new record prices. Mark Hansen of Concord Resources Ltd., a London-based trading house, sees copper blasting past its previous record high of $10,190 to trade at $12,000 a ton in the next 18 months. Trafigura Group, the leading copper trader, thinks copper is going to $15,000. “This is as big a demand shift as the urbanization of China,” says Graeme Train, a senior economist at Trafigura.

The Chinese state has been investing huge amounts of money into infrastructure for two decades, so much that the country now accounts for around half of the world’s demand for many metals. This has also forced it to get smarter about its commodity purchases.

China’s copper smelters join together to handle negotiations with the world’s miners. Chinese entities, many of them state-owned, have bought mining operations everywhere from the Democratic Republic of Congo and Peru to Indonesia and Australia. In recent years, they’ve also been buying up international trading companies.

As for what might be called the commodities of the future, China is also ahead of the game. It’s the world’s largest producer by far of rare earths, critical in all kinds of high-tech applications. It dominates the processing of the raw materials needed to make lithium ion batteries— lithium, cobalt, nickel, and graphite—which are the building blocks of the electric vehicle revolution. While just 23% of the world’s battery raw materials are mined in China, 80% of their intermediate processing takes place in China, according to Simon Moores, managing director of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, who has advised the White House on the battery industry.

In its latest five-year plan published in March, Beijing showcased how it will go about strengthening its system of reserves of energy and commodities, including through holding strategic stockpiles. An official at the country’s reserves bureau set out Beijing’s views on commodity security in an article published in a Communist Party magazine last year: Stockpile a range of commodities. That includes those in short supply, those for which there is high dependence on imports, those that exhibit large price fluctuations, and those produced in politically and economically unstable countries, the official wrote.

In the U.S., such security of supply has been of only peripheral concern. When Washington has paid attention to the geopolitics of commodities, its focus has been on the oil resources of the Middle East, and even that relationship has evolved as the shale revolution lessened U.S. dependence on imported oil. Copper and other metals have been an afterthought. While Chinese copper demand has soared over the past two decades, in the U.S. it’s fallen, analysts at Macquarie Group Ltd. point out.

The proliferation of stimulus packages means that this is surely about to change. While the details of Biden’s infrastructure push remain to be haggled over in Congress, consultancy CRU Group estimates that $1 trillion of spending could necessitate an additional 6 million tons of steel, 110,000 tons of copper, and 140,000 tons of aluminum annually.

“China has been looking at vulnerabilities in its supply chain from top to bottom for a while, and growing its strategic reserves,” says Lilley, the copper trader. “I don’t think the West has even begun to think about it. There is still a casualness here about raw material supply.”

Read next: China’s New Belt and Road Has Less Concrete, More Blockchain

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.