UN Business Falls Victim to Feuding Between the U.S. and China

UN Business Falls Victim to Feuding Between the U.S. and China

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- As hostility rises between the world’s two biggest economies, the business of the United Nations is increasingly falling prey to their competition. The U.S. and China have been feuding over everything from the novel coronavirus to 5G networks to Hong Kong, and tensions are spilling into UN meetings, adding a layer of difficulty in a place where getting things done is already hard enough. The two countries wield veto powers as permanent members of the UN Security Council, along with the U.K., France, and Russia.

“Even one or two years ago, U.S. diplomats described the Chinese as reasonably pragmatic in the Security Council, despite big differences over issues like Syria,” says Richard Gowan, UN director at the Crisis Group, a Brussels think tank. “Relations between Chinese and U.S. diplomats have cooled shockingly fast.”

In the early months of Donald Trump’s presidency, the countries managed to get over disagreements to pass tough new sanctions on North Korea, wind down some UN peacekeeping missions that were seen as costly and ineffective, and work toward stability throughout Africa. But relations have soured as the Trump administration hammers Beijing for its early response to the coronavirus, its heavy hand toward protests in Hong Kong, and its increasing assertiveness in vying for leadership of global bodies such as the World Intellectual Property Organization.

“The Security Council was frozen between 1945 and 1990 because of the Cold War,” says France’s ambassador to the UN, Nicolas de Rivière. “And the last thing that we want now is to see that happen again.”

More recently, an uncontroversial effort to call for a cease-fire in conflict zones during the pandemic stalled out as the two countries sparred. Looking ahead, the Security Council will face decisions about extending an arms embargo on Iran, keeping humanitarian aid flowing into Syria, and renewing a mandate for a mission in Afghanistan to support human rights and lay the groundwork for peace.

The tensions aren’t new. Even before the pandemic, the U.S. fought to block Chinese officials from obtaining top jobs at UN agencies and went so far as to create a new role in the State Department to counter Beijing’s rise at multilateral institutions. China, for its part, has sided with Russia to block U.S. and other Western efforts to dislodge President Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela and to provide much-needed humanitarian aid for the Syrian people.

To be sure, some diplomacy still takes place. Even now, as the U.S. and China trade barbs in public and private, they’re continuing to quietly reach understandings. When the U.S. sought to extend an arms embargo on South Sudan in late May to nudge the African country toward peace, China expressed disagreement but chose to abstain from voting, allowing the resolution to move ahead. Likewise, the Security Council came together earlier this month to extend the same measure on Libya.

But President Trump’s decision to terminate U.S. ties with the World Health Organization, a UN agency, shows how fraught multilateral diplomacy has become. The pandemic has turbocharged an increasingly adversarial relationship as Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping both focus on ramping up their domestic support.

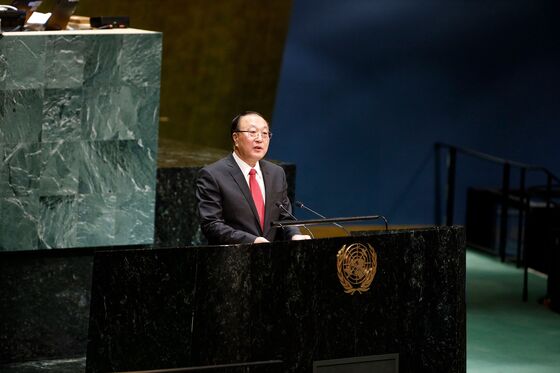

Breaking with precedent, the U.S. and the U.K. pushed the Security Council to discuss Hong Kong following Beijing’s proposal of a national security law there. That infuriated China’s ambassador, Zhang Jun, who argued in a closed meeting that Western interference in Hong Kong is akin to China interfering with U.S. protests against the police killing of George Floyd.

That sort of bombast is a shift from recent years, in which Chinese and U.S. officials sought to engage in constructive dialogue behind closed doors. Diplomats often noted that while the Russians were always eager to subvert Western efforts, China attempted to find middle ground in cases where its interests weren’t directly threatened.

De Rivière, the French UN ambassador, saw this change firsthand as he shuttled between the U.S. and China in recent weeks in an effort to get the Security Council to endorse UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’s call for a global cease-fire. The French-Tunisian initiative foundered when the U.S. sought to insert language blaming China for the pandemic, and Beijing fought back by seeking language in support of the WHO.

Perhaps the biggest test will be whether the U.S. and China, together with Russia, can avert a crisis on Iran. The Trump administration walked away from the 2015 nuclear accord signed by President Barack Obama. But now, through an opaque legal argument, it’s threatening to terminate the accord unless the rest of the Security Council goes along with its call to extend an arms embargo on Tehran. China and Russia argue that they will fight the U.S. position tooth and nail.

Whether there will be any goodwill left to find an interim solution remains to be seen. Gowan, the UN expert, is skeptical. “Trust,” he says, “seems to have evaporated.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.