Prosecutors Say They’re Spies, But Charges Tell a Different Story

Prosecutors Say They’re Spies, But Charges Tell a Different Story

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When U.S. prosecutors sought last month to throw a Chinese scientist in jail until her trial for visa fraud, a judge refused, saying they had sought to paint her as a “foreign spy” without backing up the claim. “The government suggests that this court should treat this case as one involving espionage charges, even though no such charges have been filed,” wrote U.S. District Judge John Mendez in Sacramento of the indictment against University of California at Davis researcher Juan Tang.

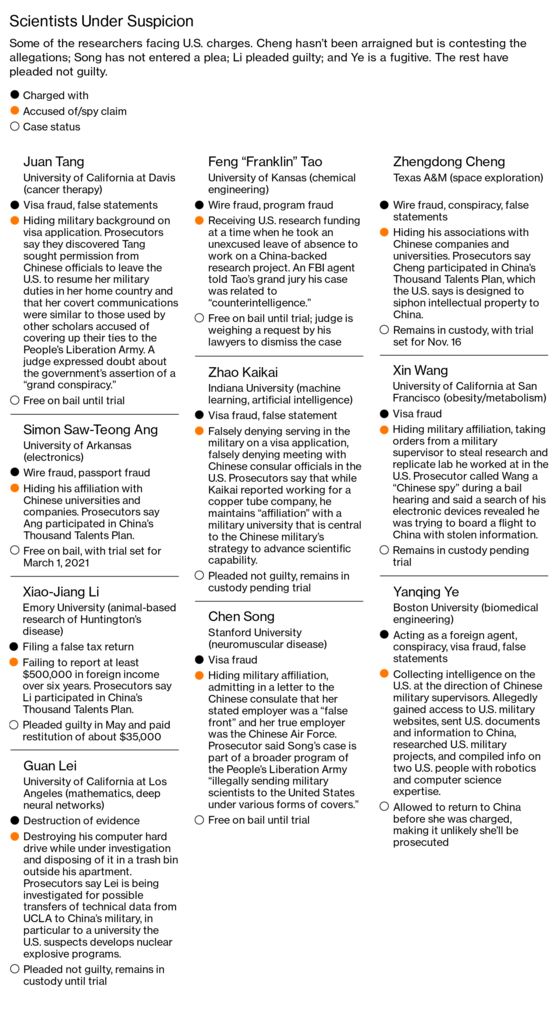

In July, when the U.S. announced charges against Tang and three other researchers who were working in American university labs, the top U.S. Department of Justice official responsible for national security said their presence in America was “part of the Chinese Communist Party’s plan to take advantage of our open society.” But the other scientists aren’t charged with spying, either, and they too face more prosaic charges.

Across the country in recent months, prosecutors have begun telling the public that they’re cracking down on nefarious behavior by visiting scientists from China, sometimes labeling them “spies” or implying their cases involved threats to national security. Six cases have been filed against Chinese researchers affiliated with military universities in their home country, and several others against visiting scholars who have participated in Chinese academic programs that U.S. authorities suspect are state-backed efforts to gather trade secrets.

Authorities say they are continuing to investigate others in 25 U.S. cities, and defense lawyers say they’re fielding inquiries from researchers worried that they’ll be deported or charged. The cases played a role in the tit-for-tat closing of consulates in the U.S. and China earlier this summer and in China’s recent threat that it may seek to detain American citizens there.

A review of court filings and transcripts of hearings shows the charges and allegations are far less serious, frequently involving misstatements surrounding a visa application—a violation often punished with less than a year in prison. In only one case has a researcher been charged with acting as a foreign government agent, and she was allowed to return to China eight months before her indictment, leaving little chance she’ll face legal proceedings in the U.S.

The heated words come in an election year when President Donald Trump has blamed China for the coronavirus pandemic and portrayed the country as a grave threat to U.S. interests, amid a broader trade battle and accusations that Chinese technology companies—from Huawei to TikTok to WeChat—are being used to pry into Americans’ private lives. Meanwhile, lawyers and academics say the tactics have the potential to chill research and deprive the U.S. of academic intellect that until a few years ago was encouraged through exchange programs. China supplies more students and researchers to the U.S. than any other country, with more than 350,000 studying and working at American schools in any given year. And American researchers collaborate with more scientists from China than any other country, according to the National Science Board.

John Demers, the assistant attorney general for national security at the Justice Department, declined a request to be interviewed. In a statement, a spokesman said: “We know that the Chinese government instructed many visiting researchers here to hide their affiliation and to destroy evidence of it. So the question to ask is why the Chinese government would engage in such behavior. We will not wait for theft to have occurred before we disrupt individuals sent here by the PRC who gave false information when gaining entry to the United States.

“Prosecutors are responsible for fairly and accurately characterizing the evidence, including by making reasonable inferences from a given set of facts, and we strive to do that each and every day.”

U.S. officials say China indeed has aggressive overseas espionage programs, including under various forms of academic sponsorships that it calls “talent programs.” The Justice Department launched a “China Initiative” in 2018 and says that 80% of its economic espionage cases involve efforts to benefit China. The initiative has resulted in several successful prosecutions for hacking and data and trade secret theft, for everything from aviation technology to rice engineering.

Peter Zeidenberg, a defense lawyer who’s represented multiple Chinese researchers charged by Justice, says the newer prosecutions aren’t addressing the harms that led to the China Initiative. “They’re taking an incredibly broad-brush approach,” he says. “They’re treating everybody as if they’re committing espionage.”

Generally, lawyers say, it’s acceptable to introduce allegations of suspicious conduct beyond the charges in a case if prosecutors can offer evidence supporting it. But “really, what you’re doing without that is just character assassination,” says Jaimie Nawaday, a defense lawyer and former federal prosecutor in New York.

The recent series of events was kicked off when Trump issued a proclamation in late May suspending student visas issued to graduate students and researchers from China affiliated with its efforts to advance China’s military capability. Since then, the U.S. Department of State has revoked the visas of more than 1,000 Chinese researchers working in the U.S.

After the proclamation was issued, China began contacting some of its researchers and telling them to return home, according to statements made to FBI agents cited in court filings. The urgency increased after the first arrest on June 7 of a researcher at Los Angeles International Airport while trying to board a flight back to China.

After that, a Chinese diplomat instructed five researchers in the U.S. to attend a meeting at the country’s embassy, where they were told to wipe their electronic devices before leaving the country in the expectation they would be questioned by U.S. Customs officials, according to a statement given to officials by a Duke University researcher identified as “L.T.” who attended the meeting. She wasn’t charged.

Not long after, the State Department ordered the closure of the Chinese consulate in Houston, citing its alleged involvement in directing researchers at a Texas facility to collect certain kinds of information, as well as instructing them in how to evade a Justice Department investigation into the matter.

“With Chinese military scientists, there’s a high level of deception,” says Alex Joske, an Australian Strategic Policy Institute analyst. “They find and study technology of value to the military. It’s not about advancing human knowledge or advancing their economy, but it’s being done to advance military superiority.”

Several recently arrested researchers came from two universities in China with high-risk reputations for trying to help the Chinese military. But if they were functioning as spies, they were sloppy. One who was under suspicion in Los Angeles for gathering sensitive data on nuclear energy development allegedly threw his destroyed computer hard drive into a trash bin while under FBI surveillance. Others were accused of lying about their backgrounds after agents researched them on the internet.

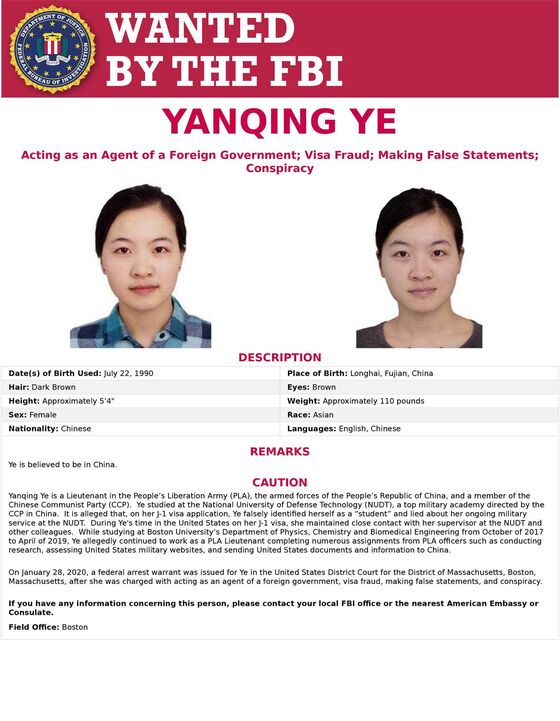

The only researcher to be charged as a foreign agent, Yanqing Ye, came to the U.S. in 2017 to study biomedical engineering at Boston University. While there, authorities say, she surveyed U.S. military websites, sent U.S. documents and information to China, researched U.S. military projects, and compiled information on two Americans with expertise in robotics and computer science for her army supervisors in China.

Ye was interviewed by federal agents in April 2019 at Boston’s Logan Airport as she was returning to China; she admitted she was a lieutenant in China’s military and a member of its ruling party. She was allowed to board the plane and return to China, where she is believed to remain. No charges were filed against her until January.

Of the researchers charged, five have been allowed to remain free pending trial and four continue to be held in custody. Tang, the researcher who was studying cancer treatments, said on her visa application that she’d never served in the military. But the FBI found an online photo of her in a military uniform. When questioned, she disclosed her ties to the school she was coming from, Air Force Military Medical University. Military hospitals are a common feature of medical care in China.

She then spent weeks at the Chinese consulate in San Francisco—where she couldn’t be arrested—and was finally apprehended after she left the building and went to a medical appointment. Charged with visa fraud and making false statements to the FBI, she was released from custody on the judge’s order last month.

Tang’s lawyer, Malcolm Segal, says it’s telling what wasn’t in her indictment. “If the government had probable cause to support its arguments and believed it had evidence to support a conviction, it would have put that case before the grand jury,” he says.

To Frank Wu, the president of Queens College and former chancellor of University of California Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco, the U.S. has crossed a line in how it’s prosecuted Tang and other researchers by insinuating, without proof, that they’re spies. “Visa fraud should be prosecuted,” he says. “It shouldn’t be prosecuted by innuendo that casts doubt not only on foreigners but also U.S. citizens that happen to look like foreigners.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.