U.K. Private Prisons Are One Industry Not Worried About Brexit

U.K. Private Prisons Are One Industry Not Worried About Brexit

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When British prison inspectors appeared unannounced at Her Majesty’s Prison Birmingham, a large private facility in central England, they encountered pools of blood and vomit on the floors. Guards locked themselves in offices to sleep during patrol hours, and inmates wandered the corridors visibly high. At one point the chief inspector, Peter Clarke, became so overcome by drug fumes that he had to leave the housing unit. Earlier that week, his team’s cars had been torched in the secure staff parking lot, according to a letter he wrote to the justice secretary last August.

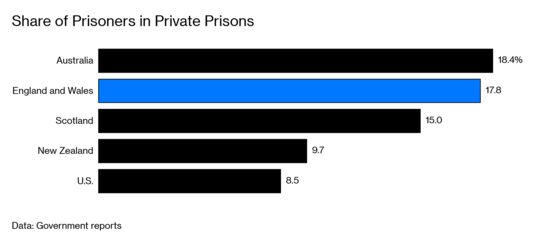

Two weeks after Clarke’s visit, ministers used emergency powers to take control of HMP Birmingham from G4S Plc, the private company that had run it since 2011. Britain holds a greater proportion of its inmates in for-profit prisons than any other country except Australia and does so at twice the rate of the U.S. Almost 20 percent of the 82,000 inmates in England and Wales are housed by three companies: G4S, Serco, and Sodexo. The private sector has an even bigger footprint in Britain’s immigration removal centers and prisoner transport services, and it also runs some of its police cells and probation monitoring. A G4S spokeswoman says the company has “no excuses” for the recent conditions at Birmingham, adding that its four other British prisons perform better.

The opposition Labour Party has promised to rein in private prison companies, accusing them of cutting corners to boost earnings. “The incarceration of human beings for profit is immoral,” says Richard Burgon, Labour’s justice spokesman. At least three other smaller opposition parties are also against commercial prisons. Critical politicians point to a string of scandals beyond Birmingham, including the collapse of a major private probations provider, Working Links, in February. A Ministry of Justice report found that Working Links compromised “professional ethics” and falsely assigned the prisoners’ risk statuses to meet targets. Fraud probes into G4S’s and Serco’s electronic-monitoring contracts are under way after a 2013 audit revealed billing for supervising prisoners who had died or left the country. Serco says it has changed internal procedures since the audit. G4S says it’s “cooperating fully” with the investigation.

Britain opened its first private prison in 1992, when the country was strengthening police powers and sentencing laws under Conservative Prime Minister John Major (“Society needs to condemn a little more and understand a little less,” Major said in a 1993 interview), a process that continued under his successor, Labour’s Tony Blair. Since then, prisoner numbers in England and Wales (excluding Northern Ireland) have almost doubled. Scotland has followed a similar path, with numbers rising more than 60 percent since 1990, although they’ve recently started declining. In Ireland they’re up about 80 percent in the same period.

Overall crime rates have dropped over the past 25 years, yet homicides, stabbings, and robberies are on the rise—a potential major challenge for an already overstretched police and prison service. Last month three teenagers were stabbed to death in Birmingham, part of a spate of knife crimes that police chiefs and politicians have termed a national epidemic.

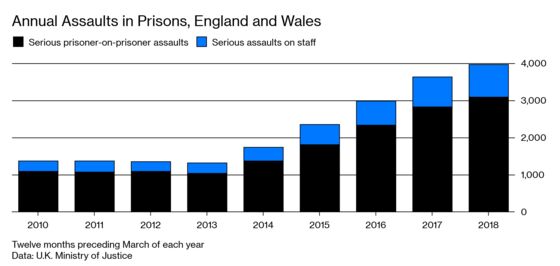

Some take the combination of privatizing and surging inmate numbers as a harbinger of dark days. “The dynamics look eerily similar to the U.S.,” says Michael Jacobson, director of CUNY’s Institute for State and Local Governance and a former New York City corrections commissioner. The U.S. has the highest total incarceration rate in the world, far outstripping both the U.K. and Australia. “We have seen the movie here, and it does not end well,” he says. In the five years from 2014 through 2018 alone, serious assaults in English and Welsh prisons have increased 130 percent, while self-harm incidents have almost doubled.

Privatization proponents say for-profit companies still have a lot to offer. Prisons Minister Rory Stewart declined to be interviewed but wrote in an email that both public and private prisons face problems and that the private sector has “played an important role” in the justice system, which he vowed would continue. Stewart, a former aid minister and founder of a nongovernmental organization in Afghanistan, told members of Parliament last year that he’d like to see prisoner numbers fall in the U.K. but that it’s unlikely to happen in the near term.

Craig Thomson, a former Scottish public prison director who now manages Serco’s Thameside prison in south London, says he was won over by the private sector’s approach. Without the “red tape” generated by government management, Thameside operates with about half the staff of a comparable public institution, he says, and spends more of its budget on facilities, including a well-equipped gym and in-cell computers. On a recent day there even the inmates seemed satisfied, and several said they prefer Thameside to London’s older public prisons. “If Serco is making a small margin and is still cheaper” than the government, says Thomson, “what’s wrong with that?”

Last year, Stewart announced plans to build six more facilities that will accommodate as many as 10,000 prisoners. Reaffirming his commitment to privatization, he told Parliament that for-profit companies will compete to run the prisons and that the public prison service would manage them only if no company provides an adequate proposal. The first two facilities, scheduled to open within the next three years, will be privately run, Stewart confirmed in November. Julian Le Vay, the former finance director of Britain’s prison service, calculates that new prison contracts could be worth more than $6 billion over the next decade, based in part on contracts set to expire that cover thousands of spaces for prisoners; the government will either renew them or run the prisons itself. “If you are in the detention business, you have got to be interested,” Le Vay says.

Burgon says his Labour Party is putting companies “on notice” and will seek to end all private prison contracts signed by Prime Minister Theresa May’s government if it comes to power at the next election in 2022—or sooner, as Brexit continues to bedevil May’s Conservative government. Marcus De Ville, Serco’s spokesman, says Labour’s warning isn’t on the company’s “immediate radar” but adds that if Britain stops contracting with Serco, it will look for more business abroad, particularly in Australia.

Meanwhile, HMP Birmingham’s future remains uncertain. Parliament is still trying to determine what went wrong, but a previous investigation following a 2016 riot there uncovered “chronic staffing shortages” and prisoners who were “policing themselves.” G4S developed a plan to improve security following the disturbance. Opposition MPs are now calling for companies to make private prison staff numbers public. The public prison service already reports its staffing, but the three private operators have resisted, arguing that it’s a commercially sensitive matter. This summer the British government will review whether to return control of the prison to G4S.

Liz Saville Roberts, an opposition MP and co-chair of a parliamentary group representing prison officers, says the lack of transparency hinders politicians from scrutinizing how private companies run their prisons. “We need to identify whether there was something happening in Birmingham that could be waiting to happen in other private prisons,” she says.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.