One of the U.K.’s Biggest Craft Brewers Is Dreading Brexit

One of the U.K.’s Biggest Craft Brewers Is Dreading Brexit

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Twelve years ago, James Watt was fishing for mackerel and halibut on a commercial trawler off the northeastern coast of Scotland. He had a dog, a modest paycheck, and few prospects in a region in decline. Today, Watt is worth $337 million and jets from Europe to Asia to the Americas managing one of the fastest-growing ventures in the U.K.

He didn’t make his fortune as a tech entrepreneur or a securities trader. He and his business partner, Martin Dickie, produce craft beer. Their company, BrewDog Plc, is known for its zesty “punk” ales and over-the-top publicity stunts: The two founders once drove a World War II-era tank through the City of London waving banners displaying their company logo, a yelping dog.

BrewDog is one of the few bright spots in a country caught in the malaise of Brexit. The company is valued at £1.7 billion ($2.2 billion) after its latest crowdfunding round and the 2017 sale of a 23 percent stake to a U.S. private equity firm. Its revenue soared 60 percent in 2018, to about £179 million, as it notched another year of net profits. And BrewDog, which sells beer in 60 countries and owns more than three dozen bars and restaurants in the U.K., has created more than 1,200 jobs in Britain.

But on a January afternoon at the company’s brewery on a windswept stretch of the Scottish coast, Watt’s mood sank when the subject of Britain’s departure from the European Union came up. Even as his employees were cranking up production on a £4 million addition to their facility, British lawmakers 560 miles to the south were clashing in a political endgame that could see the country quit the bloc on March 29 with no transition plan in place. Watt dreads that scenario. BrewDog sells more than a third of its volume in mainland Europe, and he worries the sudden imposition of tariffs and duties—not to mention customs delays—could spur supermarkets and bars to reconsider whether to carry its products. “So much of the beer we make here ends up in France and Germany and Spain and Italy, so for us that would be doomsday,” Watt says. “I might just go live in America.”

He’s only half-joking. Watt and his management team have been weighing several plans for dealing with a hard Brexit, from asking European partners to temporarily share brewing capacity to building a plant in an EU nation. He’s even contemplating shipping beer from BrewDog’s two-year-old U.S. brewery in Columbus, Ohio. “Everything is on the table,” says Watt, the chief executive officer.

The turmoil around Brexit is hitting just as BrewDog is opening the tap on many new ventures. It’s building a brewery in Brisbane, Australia, and plans another in China. The company is opening restaurants in Indianapolis and Cincinnati, and is eyeing locations in Shanghai and Kuala Lumpur. It plans to unveil its own Scotch whisky this year. By the end of January, BrewDog was expected to introduce a line of “sour beers” from a new facility at its Scottish base. Watt is betting these fruit-infused brews, which ferment in wine and whiskey barrels instead of stainless-steel tanks, will become the next big thing in the craft beer craze sweeping the U.K. and Europe.

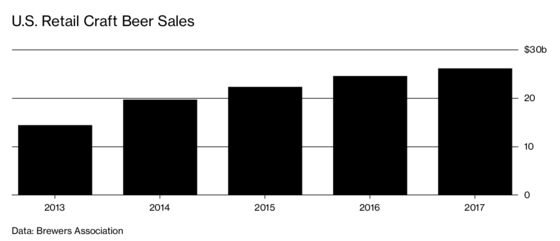

Until Brexit, BrewDog’s biggest challenge was making sure it didn’t overreach. The company is making a huge push in the U.S. just as the craft beer boom is slowing there. Sales of high-end beers from independent brewers are expected to grow about 6 percent in 2018, after double-digit annual increases in the previous three years, according to the Brewers Association, the U.S. industry trade group. That could be a preview of what’s to come in the U.K., where craft beer volume edged up 1.7 percent in 2017. Beverage industry players there fret that craft beer may be hitting a saturation point, given the flood of expansion in the segment. The number of breweries more than doubled from 2010 to 2017, to 1,930, according to the British Beer & Pub Association. And corporate giants are elbowing into the action. Last June, Heineken NV acquired a £40 million stake in London craft beermaker Beavertown Brewery Ltd. “Lots of breweries are all competing for the same segment of the market, and big brewers are taking what would have gone to smaller ones,” says Neil Walker, head of marketing at Britain’s Society of Independent Brewers.

Watt shrugs off such concerns. “We’re not too worried about demand if it’s something we’re passionate about,” he says. “Our business plan has always been death or glory.” He and Dickie have taken that let-it-rip attitude ever since they started whipping up beer batches in 2007, inspired by the hoppy pale ales of California. They filled bottles by hand, sold their brews at farmers markets, and burned through their savings. Then in 2008 the two 24-year-olds made a breakthrough when their beers took first place in a contest sponsored by Tesco Plc, Britain’s biggest supermarket chain. Told they’d just won shelf space for 2,000 cases a week, Watt didn’t blink and promised to deliver. The pair wrangled a £20,000 loan from HSBC Holdings Plc, bought some equipment, and dubbed their flagship offering Punk IPA. They vowed to fight the “insipid, artificially flavored offerings” of corporate behemoths such as Anheuser-Busch InBev NV. An early user of crowdfunding, BrewDog went on to raise £67 million from almost 100,000 “equity punks” and leapfrogged big pub chains to open their own bars.

BrewDog caught the market just as Brits, especially younger drinkers, were discovering the bracing tropical-tinged flavors that turned American craft beer pioneers such as Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. and Boston Beer Co., the maker of Sam Adams, into industry-changing forces worth billions of dollars. But what truly propelled the company was its gonzo marketing. To claim the title of world’s strongest beer from a German brewer, Watt and Dickie made Sink the Bismarck, a “quadruple IPA” with an alcohol-by-volume level of 41 percent. And they projected 60-foot-high naked images of themselves onto the Houses of Parliament to trumpet their plan to “take the craft beer revolution to the next level” (a BrewDog sign covered their private parts). Sometimes their antics flopped: In 2018 they released a beer called Pink IPA in a rose-colored can that was supposed to show support for gender equality but struck many as condescending. “People in the industry can’t stand these stunts,” says Will Bucknall, co-founder of Kicking Horse, a U.K. craft beer distributor. “But they hit the mark for their equity punks, and they increase the adoration of the brand.”

Rather than trying to just sell craft beer, the company also works hard to market a roguish lifestyle. The online BrewDog Network features beer-themed content such as the quiz show Are You Smarter Than a Drunk Person? Last year the company opened a hotel next to its Ohio brewery called the DogHouse that features taps in its 32 rooms, beer-infused soaps, and even well-stocked brew fridges in the bathrooms. “They’ve created this elusive brand equity that’s based on more than enjoying their beer,” says Spiros Malandrakis, a beverage industry analyst with market researcher Euromonitor International. “With BrewDog, you can drink a beer in the shower at their hotel.”

BrewDog’s strong branding was a big reason why TSG Consumer Partners, a San Francisco-based private equity firm that’s pumped money into consumer-focused brands including Famous Amos, Vitaminwater, and Planet Fitness, invested 100 million pounds in the company in April 2017. Despite his ubercool public image, Watt is steeped in the details of his business. His office suite features a replica of the beer shelf at a nearby Tesco supermarket so he can evaluate how the labels on his products stand out next to those of rivals. Still, he says, BrewDog remains true to its artisanal roots and will never sell out to a big brewer. “For us, the bigger companies are responsible for the bastardization and commoditization of beer, which is everything we’re against,” he says. Asked how he squares that with the TSG deal, Watt points out that iconic U.S. players such as Southern California’s Stone Brewing Co. have also tapped buyout funds. “That just helps us compete without having to sell our souls.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.