British Courts Buckle From the Strain of Covid and Funding Cuts

British Courts Buckle From the Strain of Covid and Funding Cuts

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Alejandra Llorente Tascon dreamed of becoming a criminal lawyer for years. Now the 27-year-old struggles to see a future for many of Britain’s public defenders. Based in London and self-employed (like most of the U.K.’s public defenders), Tascon says she generally earns less than the country’s hourly minimum wage after accounting for preparation work and advising clients. “The more time goes on, the more I question whether it is something I can do long term,” she says.

After the financial crisis a decade ago, Britain’s liberal-conservative coalition government introduced austerity measures. Spending on publicly funded criminal legal defense declined by 35% (in real terms) from 2010 to 2020, according to Britain’s parliamentary library; spending on civil legal defense (for cases in areas such as housing and immigration) was also heavily hit. In recent years the government has also cut the number of “sitting days” for judges, leaving some courtrooms empty at certain periods.

Lawyers have launched campaigns and held demonstrations, warning the changes would damage Britain’s justice system and hinder the right to a fair and impartial trial.

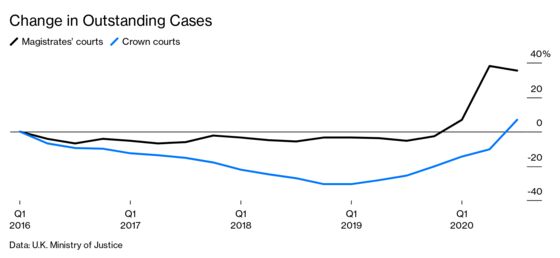

Then came Covid-19. In March 2020, as the pandemic swept across Britain, the government stopped most jury trials and suspended hundreds of courts. When they reopened at reduced capacity, the coronavirus continued to affect trials, infecting judges, jurors, defendants, and lawyers—and fueling high backlogs of cases waiting to be heard. In the third quarter of 2020, the most recent period for which court statistics are available, there were more than 53,000 outstanding cases in England and Wales’s crown courts (which try more serious crimes)—a 44% increase from the previous year—and about 412,000 cases in lower-level (magistrates’) courts. Thomas Winsor, Britain’s chief policing inspector, told Parliament’s justice committee in January of his “grave concern” about the backlogs in a system already beset by delays, decaying buildings, and chronic underfunding.

Delayed trials mean more people waiting longer in jail before judgment and sentencing and potentially weaker evidence, in part because people’s memories may fade over time. Tascon says she has clients in detention still waiting for news about when they may be tried, while one of her cases is now scheduled for 2023. “There is absolutely nothing I can do if the court hasn’t got the judges or the room to hear the cases,” she says. “Our hands are really tied.”

By the time some of the outstanding trials take place, more criminal lawyers may have left their jobs. According to a December survey of self-employed barristers (who, like Tascon, argue cases in court) by the Bar Council, the organization that represents them, 61% said they’ve had to survive the pandemic on personal debt or savings, and 20% said they were unsure if they would renew their licenses to practice this year. The Bar Council has warned that the profession’s precariousness will particularly impact Black, Asian, and ethnic minority barristers and threaten the field’s diversity. In October the council noted that some junior barristers are earning less than £13,000 ($18,000) annually pretax.

“The real danger of where we are now is that we will end up with a system far more like what you see in the United States public defender system,” says David Lammy, who’s the justice spokesperson for Britain’s opposition Labour Party. Noting the regional disparities in the U.S. court system, he adds, “There are some exceptional jurisdictions with great public defenders, but the lion’s share of them just are not of the quality we’ve traditionally enjoyed in the U.K.” The risk, he says, is if there are fewer top criminal lawyers, the system will have to resort to “people who aren’t fully qualified to take [cases] forward and very junior lawyers.”

Lammy, a former barrister himself, is also the author of a major government review into racial and ethnic disparities in Britain’s criminal justice system. Published in 2017, it noted that “there is greater disproportionality in the number of Black people in prisons here [in England and Wales] than in the United States.” Poorly funded criminal defense risks exacerbating inequities; deprived communities, often including minorities, would be less likely to access high-quality representation.

In recent months the government has opened more than 20 pop-up courtrooms in several unusual venues, including theaters, cathedrals, and hotels, to combat the backlog of cases. More so-called Nightingale courts are in the works; last summer the head of the country’s court service said 200 additional venues would be needed to clear the backlog. A justice ministry spokesman says that “legal professionals are being supported through this challenging time,” noting the government is investing £450 million to modernize courtrooms and improve technology. An independent inquiry into the future of criminal defense funding is also under way. The government announced last year it would boost annual funding for the public defense sector, and it plans to increase judges’ sitting days again.

But James Mulholland, chair of Britain’s Criminal Bar Association, says the government’s latest funding announcements are making little difference. Payment rates still remain “pretty much peanuts,” he says, and money isn’t filtering down to barristers, in part because fewer cases are being heard.

Kate Brunner, a senior barrister focusing on murder cases, hopes that the independent inquiry will lead to further investment—and that the government and public will recognize the scale of the problem in Britain’s courts. If not, she’s fearful that many of the brightest lawyers will avoid her line of work. This would mean darker days still for the country’s justice system. “We really are at a crisis point,” she says.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.