Two 737 Max Crashes in Five Months Put Boeing’s Reputation on the Line

CEO Dennis Muilenburg must wrestle with strategic choices amid the crisis.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The skies had been, in aviation parlance, “severe clear” for Dennis Muilenburg since he took the helm at Boeing Co. four years ago. With air traffic increasing 6 percent annually, orders were booming, and revenue in 2018 topped $100 billion for the first time in the company’s 102-year history. Competitor Airbus SE has been distracted with the humiliating commercial flop of its A380 flagship and a bribery scandal that’s led to a huge management turnover. With Boeing’s stock price tripling during his tenure, its market value soared above $200 billion, making it the largest U.S. industrial company. It’s used the newfound clout to pursue acquisitions and ambitious projects such as a flying car.

The only cloud was the crash in October of a 737 Max 8 jet operated by Indonesia’s Lion Air Inc. That tragic but seemingly isolated incident has emerged as the turning point in a new narrative after a second deadly accident of the same model, in Ethiopia. It’s a scenario every chief executive officer fears: public panic over product safety puncturing a carefully groomed corporate reputation. For Boeing, the pressure is acute: The 737 is a cash cow that accounts for a third of its profit.

Regulators in China, the European Union, India, Australia, Singapore, and even Canada quickly grounded the plane, and dozens of airlines have stopped flying it. British tabloids the Sun and the Daily Mail dubbed the Max 8 “the death jet.” Fleeing investors quickly trimmed more than $20 billion from Boeing’s market value. Muilenburg had to call President Trump to reassure him the plane is safe after he sent an off-message tweet decrying modern airliners as too complicated. Nonetheless, Trump and the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration belatedly ordered the jets grounded on March 13.

The two accidents weren’t identical, and there are still many unknowns. But as incomplete information rockets around the world, Boeing and the slow-to-act FAA looked isolated in a new era of airline safety in which other countries no longer wait patiently for American guidance. “What we’re looking at here is almost a rebellion against the FAA,” says Sandy Morris, an aerospace analyst at Jefferies International Ltd. in London. “It’s the first time I’ve ever seen this happen.”

Muilenburg, an engineer whose blond crew cut gives him the look of a NASA astronaut, has followed a protocol of limiting communications about investigations until clues are painstakingly gathered and the accident’s cause is unmistakable. So far, the man and the mission seem at odds in the view of some public-relations experts. Boeing’s brief statements read “like an engineer and a lawyer wrote it together,” says Erik Bernstein, vice president of Bernstein Crisis Management Inc. in Monrovia, Calif. If Boeing were his client, he says, he’d put the CEO on a 737 for the world to see and advise him to show more empathy for nervous passengers. (In a memo to employees, Muilenburg extended “deepest sympathies to the families” of the 157 people killed on the Ethiopian flight and said “we’re committed to understanding all aspects of this accident.”)

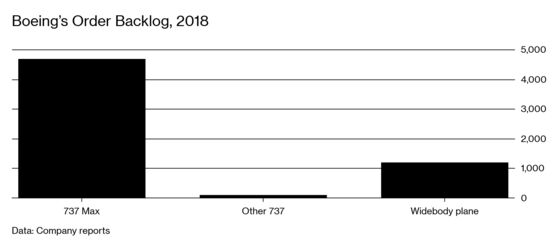

The Max jets are still a small part of the global airline fleet. The first commercial delivery of a Max was in 2017 to a Lion Air subsidiary. Boeing has since delivered about 370 from a backlog of more than 5,000 orders. The Max is an updated version of the 737, a model introduced almost as an afterthought in 1967—it was dubbed the “baby Boeing” at a time the plane maker was more focused on jumbos.

It’s since become the workhorse of the industry even though Airbus was first out of the gate with a more fuel-efficient jet, a redesign of its popular A320. As Airbus picked up massive orders for the plane, dubbed the A320neo, Boeing pursued a similar strategy, adding newer engines and making other changes to the 737 to keep pace. Production of the 737, mostly the Max version, is due to ramp up to more than two a day this year. The plane generates $1.8 billion a quarter in profit, according to Melius Research LLC analyst Carter Copeland. That’s 37 percent of Boeing’s $19.6 billion 2018 gross profit.

The Lion Air crash stirred rumbles that Boeing had skimped on investments, pushing an aging design past its limits. While the A320 and 737 are similar in size, there are notable differences, making the upgrade more complex for the U.S. company.

The 737 is a far older design than the A320, which came to market at the end of the 1980s and boasted innovations like fly-by-wire controls. The 737 also sits considerably lower to the ground, so fitting the larger engines under the wings was an engineering challenge. Boeing raised the front landing gear by a few inches, but this and the larger engines changed the plane’s center of gravity and thereby its lift. Boeing’s response for the 138- to 230-seat Max was a piece of software known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS. It intervenes automatically when a single sensor indicates the aircraft may be approaching a stall. In the Lion Air Max 8 that crashed just two and a half months after it was delivered, the pilots were baffled when the tool meant to stabilize the plane pushed the nose down dozens of times, exerting more and more force until they lost control. All 189 people aboard died when it plunged into the Java Sea.

Data from the doomed flight suggested that the so-called angle-of-attack vane provided a faulty reading to the crew of Lion Air Flight 610. Many veteran 737 pilots first learned of the flight-control changes in the Max 8 in the aftermath of the crash, and some were furious with Boeing for omitting any description of them from most flight manuals. Some said Boeing should have required special training—something it’s often loath to do because that adds costs for airlines, says former Continental Airlines CEO Gordon Bethune, who also managed the 737 program at Boeing. It’s a selling point that a new model doesn’t require pilots to get extra certification. “We had lots of discussions like this with the FAA,” he says. “It’s a give-and-take process, and Boeing normally is pretty aggressive.”

Still, there were enough oddities in the Lion Air accident—such as worsening maintenance issues repeatedly missed by its technicians—that it was largely viewed as an isolated incident. That is, until the Ethiopian jet dropped from the sky six minutes after departing from Addis Ababa. The plane flew erratically, as with Lion Air’s flight, and the pilots asked to return to the airport soon after takeoff.

Following the latest crash, Boeing sent engineering leaders and sales executives around the globe to answer questions and explain a software upgrade they hope to roll out in coming weeks. The update, which takes about an hour to download, will make sure the MCAS compares data from two angle-of-attack vanes instead of relying on a single potentially faulty sensor. There will be limits to the number of times the system can nudge the nose down and to the amount of force it exerts. The redesign has been tested in multiple flight-simulator runs and flights, but it must also be certified by the FAA.

For all the rush to judgment, it isn’t known if the software was even an issue in the Ethiopian Airlines crash. Eyewitnesses say they saw smoke beforehand, suggesting something else went wrong. Still, the plane maker could have avoided some of the blowback by moving faster to fix the software, says Peter Lemme, a retired Boeing engineer who designed the automated flight controls on the 767. “Back in November, Boeing had enough information to know that MCAS needed some fixes,” he says. “Why didn’t they get a software update out back then, as a priority, to make sure it would never be a factor again? Whatever held them back has cost them dearly.”

The FAA’s reticence to ground the Max didn’t sit well with some passengers or airlines—including Ethiopian. The carrier said on March 13 that it will ask European air-safety experts to analyze the black boxes from the crashed jet, in a remarkable suggestion that U.S. authorities might not be able to be trusted to determine the cause of the disaster after so firmly saying that the model is safe to fly.

Boeing has weathered safety questions about the 737 before, notably in the 1990s, when the crash of a United jet in Colorado Springs killed 25 people and another of a USAir flight near Pittsburgh resulted in 132 fatalities. The crashes sparked questions about uncommanded movements of the rudder. Boeing redesigned a valve that U.S. regulators suspected as a cause, and the plane remained a best-seller.

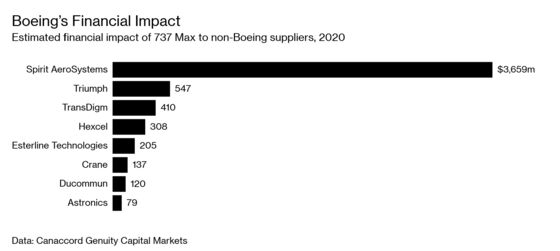

Boeing also emerged largely unscathed from the grounding of the 787 Dreamliner in 2013, after two battery fires. The jets returned to service three months after the second blaze. If the same happens to the Max, it might cost less than $1 billion to reimburse customers for lost revenue and make design updates, says Copeland, the Melius analyst.

The greater risk is to the reputation and future sales of a jet that was just establishing its bona fides with airlines. Many of these customers, such as Lion Air, are upstarts that don’t have a long history with the 737. The largest Indonesian carrier plans to cancel a $22 billion order for additional Max jets as a rift with Boeing widens. China’s regulator was the first to ground the Max, a move that may linger in the minds of the 100 million or so Chinese who’ll fly for the first time this year. The country is Boeing’s most important customer and, aside from Airbus, its most dangerous potential competitor.

Boeing may ultimately decide to become its own competitor. The decision by Muilenburg’s predecessor, Jim McNerney, to update rather than replace the 737 was controversial, with some executives pushing for an all-new plane. That costly option could be back on the table if Max sales slow. How the Max’s dinged reputation might affect Boeing’s long-term product strategy must now be addressed by Muilenburg—who received $18.5 million in compensation in 2018—and the company’s board, which includes such influential and politically connected members as a former U.S. trade representative and a retired admiral, and next month will add Nikki Haley, former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. As Gary Weissel, managing officer with Tronos Aviation Consulting Inc., puts it: “I don’t know how much more you can eke out of this design.” —With Alan Levin, Rick Clough, Harry Suhartono, and Benedikt Kammel

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.