Turkey’s Currency Crisis Tests Erdogan’s Gamesmanship

Turkey’s Currency Crisis Tests Erdogan’s Gamesmanship

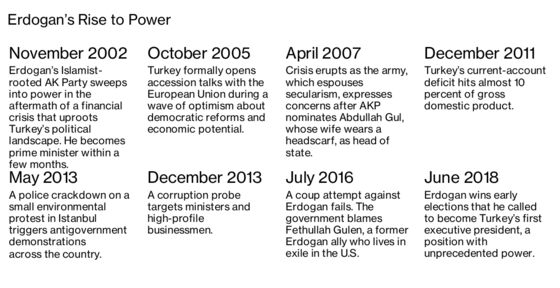

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- There’s a famous saying in politics: “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” It’s hard to think of a leader who’s put that to better use than Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. In a way, his entire political career was born out of crisis. After a stint as mayor of Istanbul in the 1990s, Erdogan was briefly jailed and his Islamist political party was banned. He then helped form a new party that was swept to power after a devastating financial crash hit Turkey in 2001. He’s now a twice-elected president who’s steadily amassed power, in part by knowing how to leverage a bad situation. He did, after all, describe a failed coup against him in 2016 as a “gift from God,” because it allowed him to crush his political opponents and endow himself with even more authority to bring about his vision for a “new Turkey.”

Erdogan knows as well as anyone the political cost of an economy going up in smoke. So why is he goading Donald Trump into tariffs and sanctions when Turkey’s economy is in so much trouble?

That’s a question U.S. officials and global investors are asking after watching the Turkish president respond to U.S. pressure by ratcheting up the tension even more. To Trump officials, it seemed like a simple enough strategy: Turn up the heat until Erdogan releases Andrew Brunson, an American pastor imprisoned in Turkey for the past two years. They didn’t expect him to risk bankrupting his own country or consider leaving NATO in favor of a closer alliance with Russia, China, and Iran. But that’s the way things are headed, or at least that’s what Erdogan wants the world to believe.

Only a month ago, he and Trump were giving each other a fist bump on the sidelines of the NATO summit in Brussels. While Trump criticized his fellow NATO leaders as weak freeloaders unwilling to pay for their own security, he had only nice things to say about Erdogan, in part because he embodies the qualities of strength and power Trump so admires.

Now, however, the two leaders are caught in a game of chicken, strongmen who pride themselves on being tough and unwilling to blink. “What we are seeing is the breakdown of a relationship between two headstrong, prickly, proud men who admired each other for their leadership styles, right up until the moment they didn’t,” says Bulent Aliriza, director of the Turkey Project at the Center for Strategic & International Studies in Washington.

What Erdogan appears to be discovering is that what worked with the Obama administration may backfire with Trump. “Previously, Erdogan could engage in this self-hostage-taking where he could say to U.S. leaders, ‘We know you want Turkey to be stable,’ effectively threatening to destabilize his own country,” says Max Hoffman, associate director for national security and international policy at the Center for American Progress. “Now you have Trump, who doesn’t care if [Erdogan] blows his own head off and is happy to hand him a loaded pistol.”

Erdogan has spent much of the past few weeks giving what sound like wartime addresses on state TV. His message has been increasingly assertive and aimed at convincing Turks their country is in an economic war. Turkey is facing a legitimate crisis. After more than a decade of debt-fueled growth, financed in large part by Western banks, the economy is in serious trouble. Rather than looking inward for reform, agree to a bailout from the International Monetary Fund, or raise interest rates, as economists and his own business leaders have urged, Erdogan has instead blamed foreign interests who he says are aligned against him. The irony, and perhaps genius, of it all is that he’s taking what by all accounts is a self-made economic crisis and selling it as an us vs. them patriotic yarn.

Still, as he rails against the U.S. at home, Erdogan continues to press for talks in Washington. On Aug. 7 he sent a team of top officials to D.C. for meetings at the State and Treasury departments. Both ended with U.S. officials refusing to negotiate until Brunson was released. A few days later, Turkey’s ambassador to the U.S., Serdar Kilic, requested a sit-down with national security adviser John Bolton. That ended the same way. According to one U.S. official who spoke on condition of anonymity, Kilic presented Bolton with the same exact plan that was rejected at the State and Treasury departments the previous week. It was odd enough to cause the official to wonder whether it was part of a broader strategy for Erdogan to appear to be negotiating in good faith while reaping the political benefits of instability.

Watching intently from the sidelines is Russia. After Turkey shot down a Russian fighter jet that had entered its airspace in November 2015, Erdogan and Vladimir Putin have worked hard to repair a relationship that had plunged into crisis. Erdogan now regularly refers to Putin as “ my friend.” The Kremlin says the two talked on Aug. 10 by phone. Three days later, as Erdogan was lashing out at the U.S. for stabbing his country “in the back,” Russia’s minister of foreign affairs, Sergei Lavrov, arrived for a two-day visit. Erdogan has touted Russia as among the alternatives available to Turkey amid the crisis. But it’s unclear how much Russia can help. Its economy is only now emerging from recession, and the ruble just had its biggest decline in three years as investors responded to another round of U.S. sanctions.

“Russia isn’t going to bail out Turkey,” says Elena Suponina, a Middle East scholar in Moscow. “Russia’s task is not to save Turkey but to maintain normal, healthy relations with it.” That likely includes keeping the country in NATO, but as an angry, disaffected member. “Of course we’ll play up the differences between Erdogan and the U.S.,” says Vladimir Frolov, a foreign policy analyst in Moscow and a former Russian diplomat. “It serves our interests better to have an offended Turkey inside NATO to undermine the alliance’s capabilities.”

And then there’s China. Turkey is a major component of President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road initiative. In July, China’s largest bank announced a $3.6 billion loan package for the Turkish energy and transportation sectors. “Turkey has clearly decided that it wants to court China,” says Raffaello Pantucci, director of international security studies at the Royal United Services Institute in London. “The question is whether China can really make a difference here and invest enough to solve Turkey’s problems.”

Despite the growing tension, the general consensus remains that the U.S. and Turkey simply depend too much on each other to allow a permanent rift. Turkey’s economy is too deeply connected to the West, while its strategic location between Europe and Asia is too valuable for NATO to lose. “I don’t think we’re marching toward a military rupture or Turkey leaving NATO,” says Soner Cagaptay, director of the Turkish Research Program at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “We’ve moved one more step to where Turkey remains a really angry ally. We’ve been moving toward that for a while.” The country has always assumed that the West wouldn’t risk losing what amounts to the second-largest military in NATO. And yet, given Trump’s inclination to question the very utility of the alliance, it’s not clear whether those past calculations are still valid.

In the end, Erdogan’s strategy may hinge less on the actions of world leaders and more on how willing his own people are to weather economic pain. There’s evidence their patience is wearing thin, particularly given the president’s repeated calls for citizens to convert their foreign exchange deposits into lira. Anyone who did so has lost money. For a leader who prides himself on having made Turks more prosperous, his failure to back his lira demands with any policy action comes as a surprise—and betrayal.

“I’ve lost about 1 million liras,” says Cahit Bas, a jeweler in Istanbul, referring to a figure that’s worth about $155,000 now, compared with $340,000 in mid-2016. “I think we’re heading for a crisis even worse than the previous one.” The economy was already bad, Bas says, then came the pastor. “They should give up the priest immediately. They should have put him on the plane with the last delegation to the U.S. ‘Here, take him!’ ” Even if the pastor does come back, relations between the U.S. and Turkey may be damaged beyond repair. —With Dandan Li, Jennifer Jacobs, and Justin Sink

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Howard Chua-Eoan at hchuaeoan@bloomberg.net, Matthew Philips

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.