TSMC Is Stuck in the Middle of a Global Panic Over Chip Supply

TSMC Is Stuck in the Middle of a Global Panic Over Chip Supply

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Decades before he founded Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Morris Chang was present at the creation of modern Silicon Valley. He reminisced at an event this April about being at an industry conference with Gordon Moore and Robert Noyce in 1958, 10 years before they started Intel Corp. The three men attended sessions all day, let the beer flow at dinner, and sang at the top of their lungs all the way back to their hotel, according to Chang. “We felt favored by the gods,” he said.

Moore and Noyce’s company went on to become one of Silicon Valley’s most legendary institutions before stumbling in recent years. It’s Chang’s TSMC that now seems like the blessed one, the result of his early embrace of an untested business model and deft execution that’s made TSMC the leader in the most advanced types of semiconductors on the market today. It dominates the smartphone sector, and its chips are in everything from cars to fighter jets. The Covid-19 pandemic further cemented its dominance. TSMC’s 2020 revenue was $45.5 billion, a 31% increase from the year before, and its adjusted net income of $17.3 billion dwarfed its profits from any previous year. The company is now worth about $590 billion, more than two and a half times Intel’s market value.

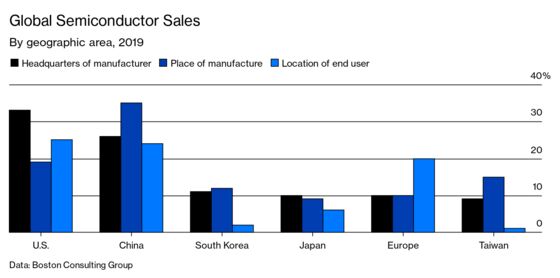

The global chip shortage has added a new layer of political sensitivity to TSMC’s business. The company does most of its production domestically, an arrangement Taiwan is eager to maintain. But the world’s biggest economies are feeling increasingly vulnerable to supply chain shocks. American, European, Japanese, and Korean officials have called on Taiwan since late 2020, angling to persuade the company to serve their national interests. Simultaneously, the U.S. and China are planning to invest in domestic production to reduce their reliance on foreign suppliers. On May 5 the European Commission also laid out plans to build up its ability to design and manufacture advanced semiconductors.

TSMC has an enormous head start, and the barriers to entry are very high. Still, it faces increased competition from Samsung Electronics Co., which is spending $116 billion on its next-generation chip business, and Intel, which plans to regain its footing by investing $20 billion on its own effort.

In April, TSMC announced a three-year plan to invest $100 billion to increase its capacity. If spent well, the money could help soothe customers’ fears of supply disruptions. But the politics and the competition have the potential to erode TSMC’s position if it doesn’t adapt. This makes the next few years the most crucial period TSMC has faced since Chang retired in 2018—and probably since he founded the company in 1987.

TSMC has always been tied closely to Taiwan. The Chinese-born Chang moved there in 1985 after becoming convinced he’d never get a chance to run an American tech company. He became chairman of a small company and took up a government research institute job, where he became inspired to start TSMC in part because of the Taiwanese government’s policies to spark the domestic tech industry.

Companies like Intel both designed and manufactured chips for their clients, but Chang envisioned a model known as the pure-play foundry, where his company would take on the intricate task of producing chips for clients that wanted to design their own but didn’t want to run the multibillion-dollar manufacturing facilities known as foundries, or fabs.

It was one of those ideas that seem obvious only in retrospect. When Chang approached Intel in 1985 to see if it wanted to invest, it turned him down. Companies that later became important partners were skeptical at first. “I was thinking to myself, ‘This is crazy,’ ” said Arm Ltd. Chief Executive Officer Simon Segars during a 2017 event celebrating TSMC’s 30th anniversary. “It turns out it is a really good idea. We wouldn’t be here today without it.”

In its early years, TSMC mostly subsisted on leftovers, picking up marginal business from early clients Advanced Micro Devices Inc. and Japan’s NEC Corp. But as it grew, TSMC developed the ability to produce cutting-edge chips. It became known for its extraordinarily consistent yield (the ratio of good vs. bad chips) and reliable delivery times, which allowed clients to chart their own investment and product cycles. By separating manufacturing from design, TSMC lowered the barriers for aspiring chip designers, empowering a second wave of players including Qualcomm Inc. and Nvidia Corp.

The really big break came in 2010, when Chang had Jeff Williams, who helped future CEO Tim Cook oversee worldwide operations for all Apple Inc. products, to his house for a home-cooked dinner. The two companies had been negotiating an agreement for TSMC to make custom chips for Apple’s iPhones and iPads, and the meal sealed the deal, Williams recounted at TSMC’s anniversary party.

It was a risk for both companies. Apple was relying on a company that was then seen as an also-ran. “If we were to bet heavily on TSMC, there would be no backup plan,” Williams said. For TSMC it meant an initial investment of $9 billion and devoting 6,000 employees to building a dedicated plant for Apple in 11 months; it took several years before it began producing the chips. The bet paid off, helping Apple reach universe-denting scale and propelling TSMC into a linchpin of the semiconductor industry while further sharpening its ability to make more sophisticated chips.

Intel failed to develop as a credible competitor in the smartphone chip market, and TSMC products became good enough to tempt Intel’s lucrative clients in the high-performance computing market to switch.

“Semiconductor users around the world know that TSMC produces more than half of cutting-edge logic chips,” says Kazumi Nishikawa, an official at Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry. “Samsung is trying to catch up, but TSMC is becoming more and more dominant.”

The pure-play foundry model has proven to be a good fit for an era dominated by huge cloud computing companies. Behemoths such as Alphabet, Amazon.com, and Microsoft are increasingly interested in designing chips for the specific needs of their data centers and artificial intelligence applications. These companies often base their chips on designs from Arm, which has been working directly with TSMC for years.

Political leaders in the U.S., Asia, and Europe have all just witnessed how vulnerable they are to disruptions in the parts of their supply chains they don’t control. For China, the Trump administration’s decision to keep U.S. companies from working with Huawei Technologies Co. added urgency to its aspirations to nurture domestic chipmaking. At the event in April, Chang said Chinese chipmakers are still years behind TSMC and urged Taiwanese officials to continue to support the company so it can maintain its position.

President Joe Biden, who’s also sought to strengthen domestic manufacturing, wants to dedicate $50 billion to U.S. semiconductor research and production. TSMC will begin building a $12 billion plant in Arizona this year, with production set for 2024 and further expansion envisioned. Samsung and Intel are already both more geographically dispersed than TSMC, a distinction the companies may be able to use to their political advantage.

TSMC has signaled a reluctance to make changes at the scale Western governments are seeking. Its international facilities have generally focused on less advanced chips, while the bulk of its capacity is in Taiwan. Chang recently questioned the logic of ramping up advanced manufacturing in the U.S. In early May, TSMC Chairman Mark Liu told CBS that the chip shortage wasn’t caused by the geographical location of chip foundries. It’s not clear that this is what officials in its biggest markets want to hear. —With Ian King and Isabel Reynolds

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.