Foreign Students in the U.S. Can Breathe Easier—For Now

Foreign Students in the U.S. Can Breathe Easier—For Now

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It wasn’t the Trump administration’s first attempt to deter foreign students, but it could have been the most disruptive. The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency sought to bar visas for international students at colleges that offer only virtual instruction. Students on existing visas would have had to transfer to a school that offers at least some in-person teaching if they wanted to remain in the U.S., or return home. The rules came as colleges and universities weighed how to reopen in the fall amid the Covid-19 pandemic, and immediately provoked anger and a flurry of lawsuits. At a July 14 hearing in Boston, U.S. District Judge Allison Burroughs announced that the U.S. had agreed to rescind the guidance.

ICE’s guidance, issued on July 6, threatened to upend the lives of students who feared deportation if their college were to pivot to online-only instruction, as schools first did in March to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus. Incoming students who need a new visa already face another hurdle: waiting for interview appointments at U.S. embassies shuttered by Covid‑19. (The State Department announced it was restarting some routine visa services on July 15, depending on location.)

The policy swiftly brought together a broad coalition of colleges, states, and businesses that opposed it. “The overwhelming negative reaction to this proposal in a very short period of time shows that the administration really struck a nerve with this,” says Terry Hartle, senior vice president of government and public affairs for the American Council on Education, which represents more than 1,700 colleges and trade groups and filed a brief supporting a legal challenge to the government. “It’s unprecedented for that many colleges and universities to file suit against the federal government.”

Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology were the first universities to seek a court order to stop the U.S. from enforcing the policy. Harvard President Lawrence Bacow said in a statement that it was coercive: “It appears that it was designed purposefully to place pressure on colleges and universities to open their on-campus classrooms for in-person instruction this fall, without regard to concerns for the health and safety of students, instructors, and others.” The Trump administration defended the rules in a court filing, claiming Harvard and MIT couldn’t persuasively argue “there is a correlation between physical presence in the United States and the quality of education” if all students are learning online.

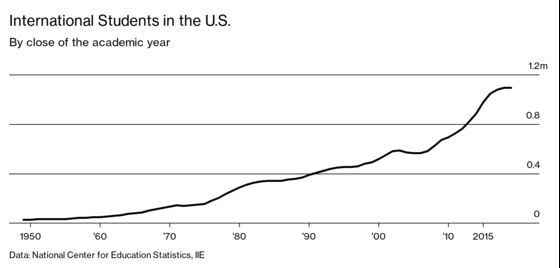

While the U.S. has long welcomed students from abroad, the rise of Donald Trump began to change that in 2016. His anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies likely persuaded some people considering U.S. schools to take their cash and talents elsewhere. By the 2018-19 school year, enrollment from abroad had stalled at 1.1 million, a gain of less than 1% from the previous year, the lowest in a decade, according to the Institute of International Education. The administration has previously tried to make it easier for foreign students to rack up “unlawful presence” violations and considered ending a popular work program for international students.

Takeharu Imai, a junior at Keio University in Tokyo who studies economics and political science, weighed graduate school in the U.S. but became wary when the visa changes were announced. “If my legal status can’t be assured while I’m studying in the U.S., then I would find it really difficult to complete an education there,” Imai says.

While the government’s reversal is good for students and schools, uncertainty about how welcome foreign students are in the U.S. will linger. “The repeated attacks on international students certainly don’t make the United States as desirable a destination as we would want,” Hartle says.

Prospective students may turn to more welcoming countries such as Australia, Canada, and the U.K., says Alan Caniglia, acting vice president for finance and administration at Franklin & Marshall College. About 20% of the undergraduate population at the school in Lancaster, Pa., is from overseas. Referring to the latest visa obstacles, Caniglia asks: “What is the message being sent not only to current students but the future cohorts of students?”

Alienating global students would be costly—for schools and the larger economy. Universities have long relied on revenue from overseas students, who often pay full tuition, subsidizing the cost of higher education for others. Institutions are already under strain, bearing unforeseen expenses and loss of revenue associated with the pandemic. They’re anticipating fewer domestic students enrolling in the fall, and as a recession sets in, many public universities are expecting budget cuts. International students contributed $44.7 billion to the U.S. economy in 2018, the Institute of International Education found.

Daniel Diermeier, a political scientist and chancellor of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, says the benefits of recruiting from abroad go beyond finances, even if the most imminent threat is gone. He speaks from personal experience, having arrived in the U.S. in 1988 as a graduate student from Germany. “You take the best grad students and put them in the best labs with the best faculty, and magic can happen,” Diermeier says. “It’s important for the university, but it is just as important for the country.” Graduate students in particular are key to U.S. universities’ research. “They have fueled the innovation economy in a whole variety of different areas,” he says. “Cutting yourself off from that supply is very shortsighted.”

Almost a quarter of the country’s billion-dollar startups had a founder who first came to the U.S. as an international student, according to a 2018 study by the National Foundation for American Policy. A loss of talent because of limits on student and nonimmigrant work visas would hurt the nation’s scientific competitiveness, say Miriam Merad, director of the Precision Immunology Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, and Brian Brown, the institute’s associate director.

“Having these scientists and students here—many of them on the visas the administration wants to suspend—has enabled America to be the leading nation in biomedical research, spurring the development of numerous life-changing and life-saving medicines,” they wrote in a letter circulating in the scientific community that has hundreds of signatories.

Almost 60 schools, including Princeton, Stanford, Vanderbilt, and Yale, filed a brief supporting Harvard and MIT’s lawsuit. California filed its own suit, saying no state has more international students than it does—almost 185,000 as of January. Its suit claimed the “attempt at a policy change to force in-person learning in the middle of a pandemic is absurd and the essence of arbitrary and capricious conduct.”

Some students already in the U.S. say they aren’t deterred. Tiffany Gu, 21, from Hong Kong, is a rising senior studying chemistry at Haverford College in Pennsylvania. Despite the uncertainty, she intends to continue studying there to get the research experience she’ll need should she choose to pursue a doctorate in the U.S. rather than in Hong Kong. “It has never been easy for international students to study here,” she says. “There’s always a lot of restrictions from the start.”

Vanderbilt’s Diermeier says it’s not too late for the U.S. to retain its advantage in the eyes of international students. “The sense of possibility that so many young people have about the United States is still alive,” he says. “It needs to be fostered. It’s very important that these things are not destroyed and inhibited.” —With Yifan Feng and Nick Wadhams

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.