Trump Tries to Follow the Rules to Win on Deregulation

Trump Tries to Follow the Rules to Win on Deregulation

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Phase 1 of President Donald Trump’s environmental deregulation agenda lasted two largely unsuccessful years. One by one, his climate proposals were crushed by legal challengers who convinced judges that the administration had failed to abide by established policymaking procedures.

Trump has so far attempted to deregulate by cutting corners: postponing compliance dates on Obama-era norms or suspending rules “pending reconsideration.” A new wave of finalized deregulatory measures is set to roll out beginning later this month, including guidelines for vehicle emission standards, clean water policies, and raised caps for greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. This time around, the president and his team seem to have discovered a secret weapon that may threaten the pristine record earned by their environmental opponents: playing by the rules.

An early Trump executive order directed agencies to get rid of “unnecessary regulatory burdens.” Many attempts to comply with the order violated provisions of the Administrative Procedures Act, which requires transparency and public participation in federal rule-making. “Now the agencies are dotting their i’s and crossing their t’s to make sure there’s adequate justification for any new rules,” says Robert Abbey, a lawyer and a director of the Bureau of Land Management under President Obama. “Determining whether that justification is lawful takes a lot of time. In the meantime, the final rule is the rule. That appears to be the strategy here.”

This time around, the legal jousting over Trump’s push for looser standards will shift to the substance of his deregulation agenda. Judges in the legal challenges that will inevitably result must decide whether these rollbacks and revisions comport with underlying statutes. That involves determining whether the Trump administration has done enough to justify them. And that means extra scrutiny of assertions about the health risks of pollution—or lack thereof—and the climate consequences of carbon dioxide emissions. “To unwind what Obama did, you have to find some way to undermine tons of science and facts that were put before agencies,” says Abigail Dillen, president of Earthjustice, an environmental law advocacy group. “It’s very hard to substantively justify this entire deregulatory agenda.”

Trump has repeatedly called environmental standards an economic burden. And while the White House released a statement on Earth Day this year saying that “environmental protection and economic prosperity go hand in hand,” even its nonderegulation agenda remains skeptical of climate change. Starting with a vow to pull the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement in 2017, Trump officials have consistently halted or impeded efforts to address environmental issues, most recently ordering the U.S. Geological Survey to stop all climate projections at the year 2040 instead of 2100. Scientists say that the most telling impacts of fossil fuel emissions won’t become evident until after 2040.

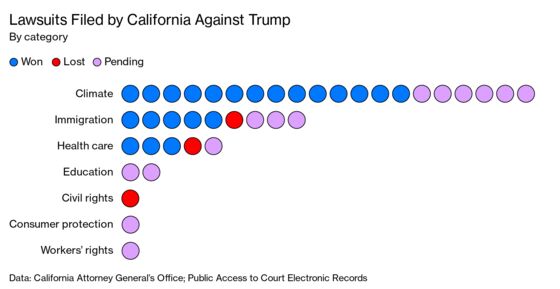

The administration’s frequent opponents in court include Earthjustice, the Sierra Club, and state attorneys general from New York to New Mexico. California Attorney General Xavier Becerra so far has amassed one of the best records, defeating 14 Trump administration deregulation measures. “I suspect President Trump considers facts unfriendly—and it’s an unfortunate thing, because they can be stubborn,” he says.

Of Becerra’s victories against the president’s deregulation measures, one of the first decided on the substance of the policy was a suit challenging the Department of the Interior’s attempt to repeal the valuation rule, an Obama-era reform affecting coal, oil, and gas companies. These companies pay royalties to the federal government on the value of the material they extract from federal land; prior to the 2016 rule, that value was often calculated based on a transaction with a subsidiary, which could be priced as low as the company wanted. The valuation rule required that they base these royalty payments on a transaction with an unaffiliated third party, which would prevent them from artificially reducing the size of the royalty payments.

After complying with public comment requirements, the department declared in early 2017 that the regulation was too “challenging” to enforce and would “unnecessarily burden” companies operating on public lands, even though an Obama administration report had found that the underpayments cost taxpayers about $17 million a year. A federal judge in Oakland, Calif., rejected the department’s argument in March 2019, finding that the new justification directly contradicted the Obama administration’s findings and that policymakers at Interior had failed to explain the discrepancy, making the proposed rule change legally unjustifiable.

The past two years have been tumultuous at both Interior and the Environmental Protection Agency. Trump’s original choices to lead the agencies were each forced to resign after allegations arose that they’d improperly used government funds. A new EPA administrator, Andrew Wheeler, was confirmed in February, and David Bernhardt was installed as Interior secretary in April, which could mean a renewed effort to roll back regulations. Neither agency responded to requests for comment.

The Bureau of Land Management’s attempts to unravel Obama’s methane waste rules, which required oil companies to repair leaks of the potent greenhouse gas, may provide a road map for the legal journey ahead. The agency’s first two attempts to postpone or suspend portions of the rule were swiftly defeated by California after the bureau skipped the public comment process. The third try went through the formal rule-making channels and attracted 220,000 comments, yielding a final regulation that met all basic public notification requirements. The two-year process upended the six-year investment in changing the rule made by the Obama administration. Becerra has filed suit in federal court to strike down the law, arguing that Trump’s agencies have failed to justify the reform, but the case won’t be heard until next January. Until then, the Trump rule stands. —With Jennifer Dlouhy

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.