Trump’s Trade War Is Hurting Farmers, But They Still Think He Can Win It

Trump’s Trade Wars Sap Spring Optimism and Profits on U.S. Farms

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Sean Gilbert surveys a two-year-old apple tree that’s head-high, a half-dozen branches growing off it at right angles. With the other trees planted at 3-foot intervals alongside, it’s part of what he hopes will be before long a lucrative wall of fruit.

If Gilbert lets nature take its course, the tree and thousands like it planted on this 20-acre orchard in Yakima, Wash., later this year will bear the first crop of Cosmic Crisp, which he and other growers in the state are calling a new blockbuster apple. If instead he chooses to interrupt the fruiting, he’ll be letting the tree reinvest its energy—think of it as the horticultural equivalent of compounding interest—into growing bigger and stronger faster, which may mean more fruit in the long term.

It’s a consequential decision: Gilbert Orchards has invested about $900,000 into the single Cosmic Crisp plot on which he’s standing. For the 122-year-old family business, Gilbert says, that amounts to a “big bet.” The gamble is all the more risky because growers like him have no experience with this cultivar. Everyone agrees that the cherry red, slightly tart, ever-so-juicy Cosmic Crisp is a good apple for eating, he says, and stays fresh as long as a year in storage. “Everything else is just guessing.”

For Gilbert Orchards, whose products wind up in fruit bowls as far away as India and Taiwan, the decision on whether to delay the first harvest of Cosmic Crisps is complicated by the uncertainty bred by Donald Trump’s trade wars. Mexico and China have hiked duties on U.S. apple imports in response to Trump’s policies. India has threatened to follow suit.

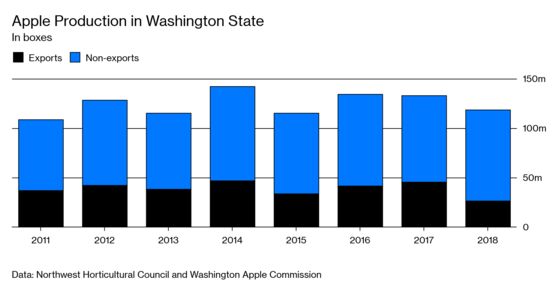

Across Washington state’s apple orchards, growers’ exports have fallen almost 30 percent since last spring. “We’ve been through these kinds of things before, but not with as many markets,” says Mark Powers, president of the Northwest Horticultural Council. “It’s not like we can divert the millions of cartons that are going to India to Costa Rica.”

Spring is supposed to be a time of optimism in rural communities across America. It’s when farmers sow the seeds of prosperity into neat, GPS-calibrated rows and when they pray for just the right amount of rain and sun and for prices to hold up so that when fall approaches, there’s a crop worth harvesting. This year is different. In Washington apple orchards, North Carolina hog farms, and soybean fields along the Mississippi River Basin, the season is filled with doubt. After taking a hit to their bottom line in 2018 of the sort that some say they haven’t seen since the 1980s, farmers in much of the U.S. are hoping for a return to normalcy.

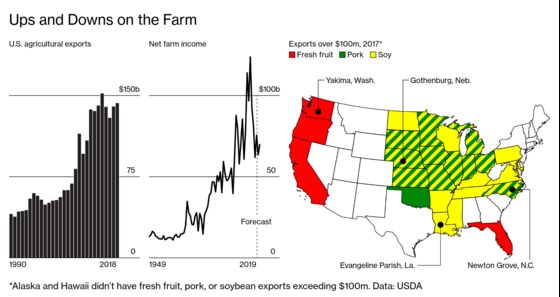

Trump’s determination to upend the global trading system comes at an inconvenient time for one of the nation’s premier export industries. No country has mastered the science of the ever-increasing yield quite like the U.S. has. It’s the world’s leading producer of commodity crops such as soybeans and corn and a major source of apples, beef, pork, and wheat. Agriculture has also been an important backer of successive administrations’ push to seal trade agreements around the world. Pacts such as the North American Free Trade Agreement have spurred agricultural exports, which have grown 170 percent over the past 20 years.

Yet U.S. farm profits have been shrinking since they peaked six years ago, amounting last year to roughly half what they were in 2013. As a result of successive years of bumper crops, prices for key commodities like soybeans and corn are about 40 percent lower than they were in 2013. At the same time, farmers have had to contend with the administration’s crackdown on immigration, which deprives them of migrant labor, and climate change, which most recently took the form of historic floods that devastated Midwestern agricultural states.

The trade wars have come on top of all that. In the year since the Trump administration launched its tariff offensive, the country’s trade partners have retaliated by hiking duties on apples, cherries, ginseng, sorghum, and soybeans, to name a few crops. It’s a familiar pattern: American farmers have long borne the cost for protectionist policies pushed by the country’s industrialists. The 1828 “tariff of abominations” designed to safeguard Northern manufacturers from an influx of lower-priced imports from Britain was opposed stridently in the agrarian South. It led to a political crisis that dogged Andrew Jackson’s presidency and precipitated South Carolina’s first threats of secession.

Conscious of the support he garnered in farm states in the 2016 election and the costs they’ve been bearing, the president last year announced an aid program of as much as $12 billion to cushion their losses. He’s also promised his trade wars will eventually be a boon for the U.S. agricultural economy, whether because of additional Chinese purchases of soybeans and other commodities or the further opening of vital markets such as Japan. “We’re doing trade deals that are going to get you so much business, you’re not even going to believe it,” he told a cheering crowd at the American Farm Bureau Federation’s annual meeting in New Orleans in January. “Your problem will be: What do we do? We need more acreage immediately. We got to plant.”

Still, plenty of people in farm country are fed up with a fight that’s only adding to the widening economic gulf between rural and urban America. “Why should just a few good patriots take it on the chin for the whole of the country?” asks Larry Wooten, the outspoken president of the North Carolina Farm Bureau.

Economists are still trying to quantify the impact of Trump’s pugnacious protectionism on agriculture. One study by researchers at Iowa State University estimated the various tit-for-tat tariffs imposed in 2018 would cost the farm state as much as $2 billion in lost economic activity, much of it in its corn and pork industries.

Calculating the drop in export revenue or the collapse in prices for some commodities isn’t difficult, but it’s harder to pin numbers on other economic consequences, such as stalled investment. Travel through farm country, and it’s hard to find a farmer who doesn’t have a story about the combine not bought or the orchard not planted.

Gilbert’s business, which employs the equivalent of 800 people full time and counts big-box retailers such as Walmart Inc. and Costco Wholesale Corp. as domestic customers, has been hit hard by the trade wars. The operation typically exports a third of its production, according to Gilbert, but shipments from the most recent harvest are down 25 percent from the previous year.

Trump’s trade wars haven’t crimped only Gilbert’s revenue; they’ve also eaten into his future profits. Instead of replanting 180 acres of the 2,000 or so he manages with new varieties like the Cosmic Crisp that fetch premium prices, he scaled back his plans last year to 120 acres.

Talk to people in Washington’s apple industry, and they mention the Cosmic Crisp alongside the Granny Smith and the Red Delicious as a revolutionary variety two decades in the making. A product of Washington State University (WSU)’s crossbreeding program, it’s a singularly crunchy apple whose flesh doesn’t brown after it’s cut. The variety is also robust enough to ship to far-off lands.

Growers in Washington state will have exclusive rights to the Cosmic Crisp until 2027. But Lynnell Brandt, whom WSU hired to manage its commercialization, already has world apple domination in mind. Anticipating success in China, he’s cut a licensing deal with a grower on the mainland, a move he hopes will deter intellectual-property thieves.

The stakes are high. With the cost of planting orchards as much as $60,000 an acre, “people are taking huge risks to try and get into a fruit that they hope will get them an adequate return,” Brandt says.

Many growers say they have no choice: Labor and other costs have been rising steadily for apple farms, even as consumers have slowly soured on industry stalwarts such as Red Delicious and Galas, which together made up about half of Washington’s crop of 120 million boxes last year, according to the Washington Apple Commission. The U.S. domestic market for Washington apples has been static for years, at about 90 million boxes. That puts a premium on developing new export markets and selling higher-margin varieties at home. Honeycrisps fetch as much as $70 a box, more than three times the price of Red Delicious.

But in apple orchards this spring, it’s easy to find signs that the trade wars are delaying the transition of an industry that’s been dominated by family-owned operations and is only starting to open up to outside capital. “You are not seeing the sort of investment in orchards or planting equipment that you would normally see,” says Powers, head of the Northwest Horticultural Council.

Nature may still wield more power to disrupt farmers’ lives than tariffs. The Iowa Farm Bureau has estimated that losses from recent flooding along the Missouri River, as well as potential flooding from local rainfall and snowmelt in states to the north, could cause more than $2 billion in damage in the state.

At Andy Jobman’s farm in central Nebraska, the Platte River, a tributary of the Missouri, overflowed its banks last month, leaving some fields under as much as 8 feet of water. When the floodwaters receded, they left behind muddy debris that needed to be carted away and a host of delayed tasks—from applying fertilizer to tilling—to prepare the fields for new crops.

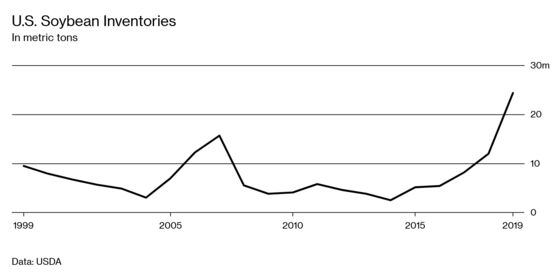

Jobman, who farms 1,200 acres of soybeans and corn with his father and brother, can’t escape the persistent uncertainty caused by the trade wars. Because of the collapse in demand for soybeans last year, his family stored some of the harvest. Aid payments doled out by the U.S. Department of Agriculture have helped plug the revenue hole, but most financial decision-making has “slowed down,” he says, because it’s hard to get a bead on where prices are headed.

One open question is whether business will revert to normal if tariffs are lifted. History has shown that even a short interruption in the supply of a commodity can have long-term consequences for American farmers. A U.S. trade spat with Japan in the 1980s that lasted only days helped trigger an increase of investment in Brazil’s soybean sector, now the biggest U.S. competitor for that crop. China’s punitive tariffs on U.S. soybean imports have prompted pig farmers on the mainland to find alternative sources of feed, says Veronica Nigh, an economist at the American Farm Bureau Federation. It’s not clear whether they’ll ever resume purchases on the same scale, even if Beijing commits to buying more U.S. soybeans as part of a trade deal.

Daniel Kowalski, a vice president of agricultural lender CoBank ACB, worries that one of the most enduring effects of the trade war may be the expansion in crop production from South America to the Black Sea “to fill space we vacated.” The reality is that, under Trump, the U.S. has so far been losing more access to lucrative agricultural export markets than it’s been gaining. The president’s withdrawal from the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership immediately after he took office left U.S. beef and pork producers at a disadvantage in Japan, as well as in fast-growing economies such as Vietnam, vs. competitors in Australia and New Zealand, which remain in the TPP. European Union farmers are also benefiting from a trade pact with Japan that went into effect on Feb. 1.

The fight with China has hurt American soybean growers and other agricultural exporters. But so have Canada’s and Mexico’s retaliation against Trump’s steel tariffs. That’s the big reason Chuck Grassley, the powerful Iowa Republican who heads the Senate Finance Committee, has said duties on Canadian and Mexican steel will have to be lifted before Congress ratifies the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, Trump’s replacement for Nafta.

Meanwhile, the productivity of America’s farm and livestock sectors keeps climbing, generating even greater food surpluses that will continue to depress prices if buyers can’t be found overseas. “Keeping farmers and agribusinesses healthy becomes more challenging if we can’t grow the export markets like we have in the past,” CoBank’s Kowalski says.

In Ville Platte, La., Richard Fontenot tills land his family has tended for five generations. The souring of the export relationship with China last year cost him $300,000 in the form of 1,000 acres of soybeans he was forced to leave in the field to rot because the grain bins on his property were already full, as were the export-driven elevators he sells to. Insurance covered some of the losses, but when he tried to tap into the aid the Trump administration made available for farmers hurt by the trade wars, he was told he wasn’t eligible because he hadn’t harvested the crop. So there’s been belt-tightening. Instead of shelling out $300,000 for a used combine as planned, Fontenot spent $30,000 to rehab his existing machine. “I had a crop in the field that I couldn’t export because of the tariffs,” he says.

Fontenot, who like many farmers in what’s known as the Cajun Prairie raises rice and crawfish alongside his soybeans, is keeping a wary eye on a near-record stockpile of soybeans nationally and on the Mississippi’s high waters. He remains a Trump supporter, as are most voters in Evangeline Parish, where the president won almost 70 percent of the vote in 2016. His hope is that the losses he’s taken on soybeans will be salved by future rice sales to China. “He’s costing me money today, but I think he’s going to make me money in the future,” Fontenot says.

Trump’s tariffs—and the effect they’re having on investment—are hurting business at Hog Slat, the 50-year-old family business David Herring runs with his brother in the North Carolina hamlet of Newton Grove, where their grandfather’s hardware store once stood. Hog Slat makes everything it takes to build the vast sheds that house pigs, from the slotted floors that gave the business its name to feed bins and ventilation systems. It also assembles the sheds. Over the past year, its business has slowed.

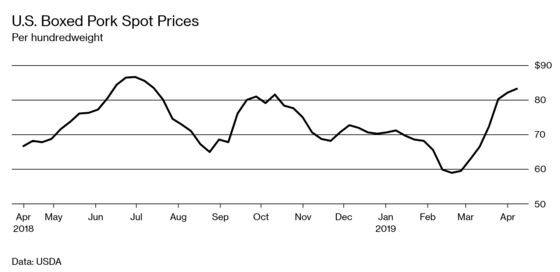

There have been other blows, too. Steel tariffs raised the price of the domestic metal the company uses. Herring’s own hog business was hit by the retaliatory duties imposed by Mexico, the biggest export market for U.S. pork by volume, and the resulting collapse in prices. Hog Slat is a private company, and Herring, who earlier this year assumed the rotating presidency of the National Pork Producers Council, won’t disclose its financials, saying only that “there was a lot of money lost” and he had to lay off 80 of his 1,500 employees in the U.S.

In a community where conservatism is the rule, farmers remain optimistic that the president they voted for in 2016 will live up to his pledge to make it up to farmers, Herring says. It helps that they’ve benefited from Trump’s deregulatory agenda, including laxer federal rules for water use, as well as cuts to business and estate taxes. But “patience is not where it was six months ago,” he says. And that forbearance may not survive another year like the last.

For Lorenda Overman, 2018 was the worst year she’s seen in the 37 since she married a farmer and moved onto the patch of North Carolina that her husband’s family has owned and nurtured since before the Revolutionary War. There was the economic storm that came in the form of the trade wars, and then there was Hurricane Florence, which turned harvest time into a scramble to salvage crops. For the first time, the Overmans had to delay writing the monthly checks that support the families of two of their grown children, who live and work alongside them on the farm. “You are taking the food right out of the mouths of your grandchildren,” she says.

Now she’s worried about numbers that don’t pencil out even before some crops have been planted. At current prices, this year’s corn, wheat, and soybeans are set to yield almost $290,000 in losses, by her calculations. And that’s if nothing else goes wrong. But she hasn’t lost hope in Trump. If the man whom she voted for and cheered from the sixth row at the Farm Bureau convention cuts a deal with China, she hopes markets will respond. “A swipe of the pen, and those prices can bounce back,” she says.

Some of the changes brought on by Trump’s trade offensive may linger, though. The 7,500 hogs that spend 18 weeks at a time housed in six sheds on the Overmans’ farm in Goldsboro are owned by what’s known in the industry as an “integrator.” To fatten them up from 10-week-old piglets into 250-pound to 300-pound beasts, the family is paid a set rate that hasn’t changed in a decade. But in part because of trade war losses, the integrator will be phasing out its multiyear contracts and replacing them with 120-day ones, a switch that will leave the family more exposed to the vagaries of the markets. The change won’t happen till 2021. Overman hopes the family business can stick it out until then. “I’m praying every night,” she says, “that we are not in the same place we are a year from now.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.