Trump’s Trade War Threatens to Divide the World’s Smartphone Makers

Lesson for Apple investors, it was one that their counterparts in China already know well: There’s no escaping geopolitics.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- During an earnings call last May, Apple Chief Executive Officer Tim Cook told investors he wasn’t worried about President Donald Trump’s trade war with China. The world’s two superpowers were too intertwined, Cook argued, for either one to try to seriously damage the other. “China only wins if the U.S. wins, and the U.S. only wins if China wins,” he said. “And the world only wins if China and the U.S. win.”

Just after the market closed on Jan. 2, Cook had a different message. For the first time in 15 years, Apple Inc. cut its revenue projections. The CEO explained that the Trump administration’s trade policies had hurt demand for iPhones in China. The following day, Apple lost 10 percent of its market value. Its decline fueled a broader sell-off among investors already spooked by the sudden possibility that the once-inexorable march of globalization could be reversed.

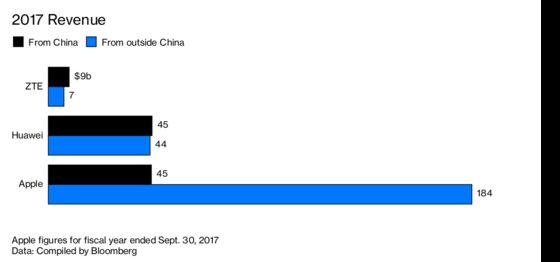

If there was a lesson for Apple investors, it was one that their counterparts in China already know well: There’s no escaping geopolitics. Huawei Technologies Co. and ZTE Corp., the big Chinese phone and equipment manufacturers, have been under intense pressure from the Trump administration, which is seeking to limit China’s control of fifth-generation, or 5G, wireless networks. The new technology will power not only smartphones but also autonomous vehicles and connected infrastructure. Chinese dominance over such a vital new technology poses a potential security risk, at least according to U.S. intelligence agencies.

The fear is that the Chinese government would force these big companies to include back doors in their equipment, a notion that the Trump administration has used to lobby allies against granting contracts to Huawei or ZTE. In late December, Reuters reported that the administration was considering an executive order that could block U.S. carriers from working with the two companies, citing anonymous sources. The companies both adamantly deny spying charges, noting there’s no public evidence to support them. In China, it’s commonly believed that Trump’s real goal is to stymie economic competition.

Chinese and American officials met to discuss trade policy on Jan. 7, the first face-to-face talks since Dec. 1, when Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping met in Argentina to address the mounting tension. On that same day, Canadian law enforcement officials, working at the behest of the U.S., detained Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s chief financial officer, while she traveled through Vancouver. The U.S. has accused Meng of fraud in connection with alleged violations of sanctions that prohibit doing business with Iran. Meng denies the charge. She’s out on bail, awaiting a formal extradition request.

It’s still not clear how the diplomatic dispute between the U.S., Canada, and China will be resolved, or what bearing it might have on Huawei’s long-term health or the demand for Apple’s products in China. But for a preview of the power dynamics that are roiling the global technology industry, it’s worth looking at the case of ZTE, which narrowly avoided becoming a casualty of the trade war last spring. In April 2018, the U.S. Department of Commerce announced that the company, which like Huawei is based in Shenzhen, hadn’t complied with a settlement related to its own violations of Iran sanctions. The Trump administration’s punishment: a seven-year ban on working with U.S. suppliers.

The consequences of the ban weren’t clear at first, even to some at ZTE, who didn’t see its U.S. operations as particularly important. “My initial reaction was, ‘So what?’ ” says a Shenzhen-based employee who spoke to Bloomberg Businessweek on the condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to speak publicly. “Most of the equipment we’ve been making was targeted for China and Central Asian markets. But then some production lines stopped running and many workers started to ask questions. That’s about the time when I realized the company was doomed.”

ZTE, like all the major telecom manufacturers, makes phones and equipment in China, but relies heavily on U.S. suppliers for components. In fact, certain critical parts, such as networking switches and cellphone modems, are made only by U.S. companies. Cut off from such components, ZTE immediately began furloughing workers and closing factories. “Major operating activities of the Company have ceased,” it said in a financial filing in early May.

And then, just as suddenly, President Trump reversed course, tweeting on May 13 that he’d reached a deal with President Xi to save ZTE. “Too many jobs in China lost,” he tweeted. “Commerce Department has been instructed to get it done!” ZTE had been spared, but the message was clear: Trump, if he wants to, has the power to cripple or even kill China’s biggest telecoms.

Global tech executives like Cook often laud interdependence as a moderating influence, but it can also be weaponized. China hawks in Washington began referring approvingly to the prospect of the “death penalty,” for Huawei or ZTE, or both. “ZTE’s head is arguably still in the noose. It’s just not standing over the trapdoor,” says Dean Cheng, a senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation. “It wouldn’t take much to put them back over the trapdoor.”

ZTE’s origin story starts with a trip to the U.S. that Hou Weigui, a middle-aged employee of China’s state-owned defense industry, took in the mid-1980s. Hou, who retired in 2016 and is now in his late 70s, returned to his post at the Ministry of Aerospace and Industry’s 691 Factory in Xi’an feeling inspired at the state of Western innovation. “I was also fully convinced China needs its own telecom equipment maker,” he said in a 2013 interview with Xinhua News Agency, China’s state-run news outlet.

It was an auspicious time to come to such a conclusion. Under Deng Xiaoping, China was opening up to limited forms of commercial activity. In 1985, Hou and several colleagues formed a company with 2.8 million yuan, or just over $2 million in today’s dollars. Its name, Zhongxing, translates to “prosperous China.” (The “TE,” added later, stands for “telecommunications equipment.”)

ZTE started as a contract manufacturer and made products such as landline phones, electronic organs, and electric fans. It began developing networking equipment in 1987, finding a foothold by underselling foreign competitors. It eventually won contracts to build large private communications networks for railroads, hotels, and government agencies.

Because of the early connections to Beijing, ZTE (like Huawei, which was founded by a former military officer) has long fought the assumption that it’s a tool of the Chinese state. ZTE has said the government first secured an equity stake when the company went public in 1997. According to financial disclosures, state-owned enterprises hold a 48.5 percent stake in a company called Zhongxingxin, which in turn owns about 30 percent of ZTE’s shares. On its website, ZTE says it has a novel business model—“state-owned and private-run”—and that the government isn’t involved in day-to-day operations.

For its part, the U.S. has never been convinced by China’s corporate autobiographies. “Based on available classified and unclassified information, Huawei and ZTE cannot be trusted to be free of foreign state influence and thus pose a security threat to the United States and to our systems,” wrote the U.S. House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence in a 2012 report.

Almost as an aside, the committee mentioned that ZTE hadn’t satisfactorily responded to press reports that it was doing business with Iran, the issue that would lead the company to the brink years later. ZTE began secretly working with Iran as far back as 2010, according to a settlement the company later reached with the U.S. Knowing that sending American components to the country, even as part of Chinese-branded equipment, violated U.S. sanctions, ZTE set up shell companies, removed logos from packages, and spoke about customers in code. Countries the U.S. considered state sponsors of terrorism, for instance, were “Category Z.” Iran was referred to as the “Middle East.”

The company’s dealings eventually became public, and in 2017 it admitted to evading sanctions on Iran and North Korea and agreed to pay as much as $1.2 billion in fines and penalties. The matter seemed settled until last April, when the Commerce Department announced that ZTE had paid bonuses to the executives involved in the sanctions violations, misleading U.S. officials.

At ZTE’s U.S. headquarters, consisting of two buildings in an office park in suburban Dallas where 350 of the company’s 80,000 employees worked, news of the death penalty was met with confusion. Local executives gave no instructions for weeks, according to a former employee who asked for anonymity to avoid possible retribution from the company. This person says many workers in the U.S. felt ZTE was being singled out for political reasons but also resented the company’s leadership for misbehavior that invited legal consequences. ZTE was a little fish compared to Huawei, this person says, which made it an easier target.

Panic was mounting in Shenzhen as well. Then several days before Trump’s tweet, ZTE’s leadership sent an email to the staff there saying a deal could be imminent. “Hold your roles, keep the employees managed, and stabilize the morale of the troops,” said the email, a copy of which was viewed by Bloomberg Businessweek.

When Trump’s reversal was announced, ZTE employees rushed to post screenshots to WeChat, the Chinese messaging app. An optimistic message appeared on a large LED screen in the lobby of its headquarters: “With one heart and mind, let’s keep the faith and expect the dawn.” ZTE’s leadership followed up with another email to the staff, acknowledging the crisis. “Our management and employees must reflect on this issue and learn the lesson,” it read. When a deal with the U.S. government was finalized in June, ZTE had agreed to pay a $1.4 billion fine and replace its senior executives and its board. In the aftermath, the company cut back on its smartphone operations and sold hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of real estate to help pay its fines.

The reprieve may prove to be temporary. Some Republicans objected to Trump’s deal and tried to block it. When that failed, Marco Rubio, a Republican senator from Florida, and Chris Van Hollen, a Maryland Democrat, introduced legislation that would immediately reinstate the import ban if ZTE were found to violate U.S. sanctions. (It hasn’t advanced.) When a Reuters report in November said that ZTE has supplied technology for a surveillance program run by Venezuela, a country whose leaders are subject to U.S. sanctions, Rubio and Van Hollen asked the Commerce Department whether this would violate the agreement. The department has yet to respond.

To China’s political leaders, the ZTE episode served as inspiration to reduce the country’s reliance on America’s tech industry. In April, according to Xinhua, President Xi gave a speech arguing that “core technologies are important instruments of the state.” The implication: China should make the chips that would free its tech companies from U.S. suppliers. Since then, Huawei has made several announcements about progress on new semiconductors that would compete with those from U.S. chipmakers such as Intel, Nvidia, and Qualcomm.

Tensions simmered over the following months as several U.S. allies indicated they wouldn’t work with Huawei or ZTE on 5G. Then came Meng’s arrest. The coincidental timing (if it was in fact a coincidence) created the appearance of a Corleone-esque power play, as if Trump or members of his administration were sending a message to Xi.

U.S. officials told reporters that the Trump administration hadn’t known about or directed the arrest. But the president himself told Reuters on Dec. 11 that he viewed Meng as a potential source of leverage in trade negotiations. “I would certainly intervene if I thought it were necessary” to secure a deal with China, he said.

Not surprisingly, the Chinese were outraged. Authorities quickly arrested two Canadians in what was widely seen as a retaliatory measure. And an editorial published in the state-owned Global Times argued that Meng’s arrest had been part of the Trump administration’s “containment strategy aimed at holding back China’s economic development.” It predicted that other businesses would soon be singled out for political punishment.

Chinese companies remain vulnerable, because they are years away from being truly independent from Western technology, says James Lewis, a former U.S. Department of State cybersecurity expert now affiliated with the Washington-based Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS). But he doubts China would let the U.S. drive its companies out of business, and says attempts to do so could hurt American interests in the long run. “The ZTE cutoff, if anything, accelerated the desire to escape dependence on American technology,” he says, adding that China will become more aggressive the less it needs the U.S. “It was a really bad idea.” There are already signs of a backlash against American tech in China. After Meng’s arrest, some Chinese companies offered financial incentives to employees who chose products from Huawei over Apple.

In a sign that Huawei isn’t holding out much hope for repairing its image in the U.S., the company has mostly abandoned its lobbying efforts in Washington. ZTE has taken the opposite approach. It spent more on lobbying in 2018 than in the previous three years combined and recently hired former senator and vice presidential candidate Joe Lieberman. Asked to describe his role, Lieberman says it’s “not to advocate or persuade but rather to carefully listen so that ZTE can learn with some precision the exact nature of U.S. concerns and then hopefully address them.” On Jan. 2, Elizabeth Warren, the Massachusetts senator and likely presidential candidate, blasted ZTE for its connections to the Chinese government and Lieberman for “blocking accountability.”

As her comments suggest, many American policymakers have already made up their minds on China’s tech companies. At a congressional hearing in May, Representative Anna Eshoo, a Democrat from California, asked Samm Sacks, a senior fellow at CSIS, what it would cost to eliminate Chinese equipment from U.S. telecommunications altogether.

“There has not been public information released about the specific problems associated with Huawei and ZTE,” Sacks replied. “I am not saying they don’t exist, but in order to conduct that kind of assessment to do the kind of—”

“Let me interrupt you just a second,” said Eshoo. “I know from classified briefings what the challenges are. I am not asking you to tell me about that. I already know that. The challenge is, we want to have a system where we are not reliant on them for anything. For anything.” —With Yuan Gao

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Max Chafkin at mchafkin@bloomberg.net, Jim Aley

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.