Trump’s Tax Cuts Made a Difference in 2018. Just Not the One Backers Were Hoping For

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that President Donald Trump signed a year ago seems to have boosted the U.S. economy in 2018.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that President Trump signed a year ago seems to have boosted economic growth in 2018. But there’s little evidence yet that it’s setting up the U.S. economy for faster growth over the longer term, which is what the White House and the legislation’s backers in Congress promised.

There’s a lot we still don’t know about the impact of the TCJA, given that the tax code is just one of many variables influencing the economy. “There will never be the smoking-gun study that says, ‘This was the effect,’ ” says Joseph Rosenberg, a senior research associate at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

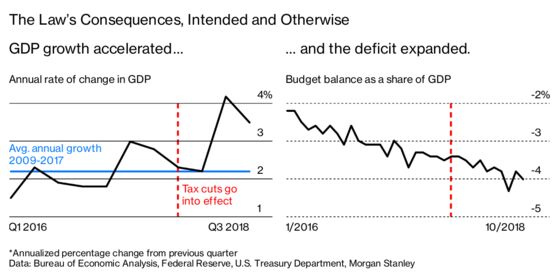

The early results were impressive. Growth, which has averaged 2.2 percent a year since the end of the recession in 2009, accelerated to 4.2 percent in the second quarter, on an annualized basis, and a still strong 3.5 percent in the third. The robust expansion helped drive down unemployment in September to a 49-year low of 3.7 percent, where it remains.

The tax cuts gave a Keynesian boost to demand for goods and services, so its effects are quickly wearing off as the fresh demand is sated: Economists surveyed by Bloomberg expect annualized growth to decline to 2.6 percent in the current quarter, then continue to slow to reach 2 percent by the end of 2019.

Consumer spending, for example, jumped this year because most households got tax cuts. Households have been spending some of the money no longer being withheld from their paychecks. The impact won’t fully be known until we see how consumers react after receiving refunds for the 2018 tax year next spring, says Constance Hunter, chief economist at KPMG LLP. In any case, the cut is causing a one-time step up to a higher level of spending, not continuing growth.

While the TCJA got most of the attention, spending increases approved after most of the tax changes took effect probably had an even bigger impact on growth. The Bipartisan Budget Act that Trump signed in February lifted caps on defense and nondefense spending. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that tax cuts added 0.3 percentage point to the fiscal 2018 growth rate; the easing of the spending caps added another 0.3 percentage point. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates that various other spending increases, including disaster assistance for victims of hurricanes Florence and Michael and the California wildfires, added an additional 0.2 percentage point.

Economists tend to agree that the fiscal stimulus would have done the economy and workers more good if it had been passed in, say, 2013, when the unemployment rate was more than 7 percent. Nevertheless, it was still useful in creating jobs for the chronically unemployed, including people in parts of the country where the recovery arrived late, says Michael Englund, chief economist of Action Economics LLC, a forecasting company in Boulder, Colo.

One of the most easily disproved claims Trump made about his tax cut plan is that it wouldn’t swell the budget deficit: As a share of gross domestic product, the deficit rose to 4 percent in October, up from 3.4 percent in October 2017 and 2.6 percent in October 2016.

A temporary growth bump is nice, but what of the transformative effects that Trump and others campaigned on? Nine top conservative economists wrote an open letter in November 2017 arguing that the tax bill, by encouraging more business investment in equipment, software, and buildings, could increase the size of the economy by 3 percent over a decade. Yet there’s scant evidence of a sustained pickup in investment.

The tax law removed the disincentive in the tax code for U.S. companies to bring home their foreign profits. Trump predicted a $4 trillion windfall. Data compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis show that $295 billion was repatriated in the first quarter of 2018. That dropped to $170 billion in the second quarter and is on track to fall below $100 billion in the third quarter, not far above the $40 billion post-crisis quarterly average, Morgan Stanley economists estimated in early December.

Perhaps U.S. multinationals don’t see enough good opportunities to put their money to work at home, says Tim Mahedy, an economist for Bloomberg Economics in New York. That would be consistent with an October survey of 116 U.S. companies by the National Association for Business Economics, which found that 81 percent hadn’t dialed up their planned investment—or hiring—because of the tax law.

Business investment did jump in the first quarter of 2018, presumably in response to the tax cuts, but then quickly sagged toward its normal range. For it to raise the economy’s growth rate over a longer term, it would have to climb to a much higher level and stay there, according to a recent report from Barclays Plc.

Optimists might argue that companies take a long time to plan and execute major new investments so a boom will show up soon, but that appears less likely with each passing quarter. “The fact that we still have the argument, in our view, is prima-facie evidence that the hoped-for improvement in potential growth is not happening,” write Barclays economists Jonathan Millar and Michael Gapen.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.