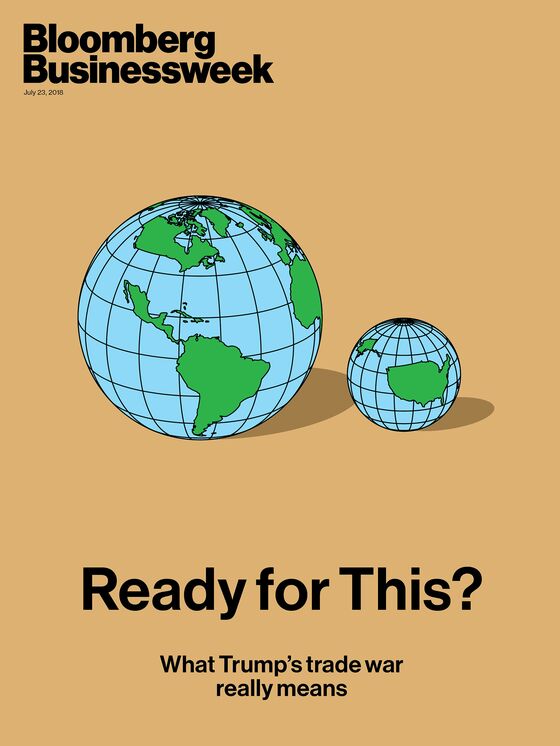

Trump’s Damage to International Trade Will Take Years to Repair

Trump really could wreck the international institutions that have been built up since World War II.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Is President Trump a blip? A brief aberration who will have no lasting impact on international relations? A tempest in a samovar? Don’t count on it. In a matter of days the president has instigated a trade war, insulted the leaders of numerous allies, thrown NATO into shock, labeled the European Union a foe, and held a remarkable press conference with Russian President Vladimir Putin on July 16 in which he endorsed Putin’s suggestion that Russian intelligence agents could help the U.S. sort through allegations that Russians meddled in the election that brought Trump to power.

There are two reasons to expect that Trump’s impact on the world order will be lasting. One is that his actions are eroding trust among both allies and rivals. Once gone, trust is hard to reestablish, even if the next president turns out to be a devoted internationalist. The other is that he is pushing a boulder downhill—the boulder, of course, being nationalism. Like the politicians behind Britain’s “leave” campaign, he’s both harnessing and amplifying powerful emotions that tend to drive countries apart and keep them apart. “The populist sentiments for isolationism and protectionism in the U.S. are not created by Trump,” says Lawrence Lau, an economist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “He has merely exploited them very effectively.”

That makes Trump a big problem for Big Business. U.S. corporate leaders soft-pedaled their criticisms of his trade policies in the past because they hoped he’d come around to their point of view. And they were grateful for his strong support on two other key priorities: tax cuts and deregulation. Now they worry that waiting for the squall to pass may be a mistake because real damage could be done in the meantime.

You can sense the frustration in Joshua Bolten, a free-trade Republican who was President George W. Bush’s chief of staff and is president of the Business Roundtable, an organization of large-company chief executive officers. He testified on July 12 against the tariffs Trump has unilaterally imposed on steel, aluminum, and other products. “I have heard people in the administration say, ‘You know, OK, but don’t worry, it’s going to get resolved, it’s going to take a little, everybody needs to absorb a little pain in the short run,’ ” Bolten told Trump critic Bob Corker of Tennessee, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Bolten rejected such reassurances: “When you disrupt supply chains, when you demonstrate that we are an unreliable trading partner, you lose those relationships permanently.”

U.S. financial markets have largely shrugged off fears of a trade war because the amount of goods covered by higher tariffs is small. The S&P 500 stock index is up 5 percent this year. Economists estimate that the tariffs imposed so far would knock no more than a tenth of a percentage point off the growth rate. “I think the market is right in thinking that the most likely outcome is that free trade survives but with tweaks,” says Mohamed El-Erian, a Bloomberg Opinion columnist and chief economic adviser at Allianz SE. Speaking to Bloomberg News on July 16, BlackRock Inc. CEO Larry Fink said, “Right now it’s all talk.”

Still, the threats and counter threats create uncertainty that may induce businesses to hold back investment in new plants and equipment, known as capital spending, or capex. “Global business sentiment, linked to positive news on profits, has been an important driver of the recent global capex upturn,” JPMorgan Chase & Co. economists wrote on July 13.

And all bets are off if the trade war goes hot. Fink warned that stocks could fall 10 percent to 15 percent if the Trump administration approves tariffs on an additional $200 billion of Chinese imports. Although El-Erian says the U.S. could face down China in a trade war because China, which exports more to the U.S. than vice versa, has more to lose, he says, “There’s a reason you don’t embark on this approach lightly. You can end up in massive confrontation.”

That’s the immediate risk. In the longer term, trade barriers make the global economy permanently less efficient because sheltered economies produce things that could be made more cheaply elsewhere. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development estimated this month that if countries restored their tariff rates to their 1990 levels, wiping out almost 30 years of reductions, world average living standards in 2060 would end up about 14 percent lower than in the OECD’s baseline scenario. “Short-lived disputes can have very long-term consequences,” says Jamie Thompson, head of macro scenarios at Oxford Economics.

The idea of going back to a world of higher tariff walls is no longer out of the question. Joseph Nye, 81, a political scientist at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, asked last September in a commentary for the Project Syndicate website whether Trump’s presidency was a “temporary aberration” in world affairs. He thought it might be. “At that time, it was plausible to argue that some of his more outrageous behavior was part of his traditional bluster in a bargaining routine,” Nye, who served as chairman of President Bill Clinton’s National Intelligence Council, wrote in a July 15 email. “Now, after his European visit and tariff war, we have to consider the hypothesis that his intent is to destroy the institutions of the liberal international order.”

If he chose to, Trump really could wreck the international institutions that have been built up since World War II, because the U.S. is their linchpin. That goes for the World Trade Organization, the United Nations, NATO, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank, all of which were co-founded by the U.S. in its enlightened self-interest. It would be hard for them to function if the U.S. withdrew or declined to cooperate. American obstruction is already a problem for the WTO. The Trump administration refuses to confirm nominees to its appellate body. If Trump continues to block appointments, the de facto appeals court will be paralyzed by next year because it won’t have the minimum of three panelists required to sign off on rulings.

One indication that Trump’s influence will be lasting is that foreign opinion has turned against the U.S. as a nation, not just against the president. Approval of U.S. global leadership slipped from 48 percent in 2016 to 30 percent in 2017, just behind China and only slightly ahead of Russia, according to a Gallup World Poll. People don’t always make the distinction between the country and the person leading it—fair enough considering the U.S. is a democracy. “We need to ask why the United States elected him in the first place and why his popularity is so high,” says Cheng Li, research director of the Brookings Institution’s John L. Thornton China Center.

Trump has defenders. He has “pushed Americans to recognize” that “the Clinton-Bush-Obama strategy of engagement has failed to elicit from China either a more cooperative foreign policy or a less mercantilist economic policy,” says David Denoon, a New York University economist who says he’s sympathetic to Trump’s aims, though not his tactics. Economic Strategy Institute founder Clyde Prestowitz says, “Questions that should have been raised a long time ago are being brought forth now, not always in the most delicate and well-spoken fashion.” In a Project Syndicate commentary published on July 17, Yale University economist Robert Shiller calls the trade war “an international tragedy” but says some good could come of it “if it eventually reminds us of the risks that free trade imposes on people, and if we improve our insurance mechanisms to help them.”

There’s a good chance that the next U.S. president, whoever it may be, will continue to be tough toward China but do so in concert with allies and through existing bodies such as the WTO. There’s bilateral support in Congress for cracking down on anticompetitive Chinese practices, and it predates Trump, argues Pauline Loong, managing director at research company Asia-analytica in Hong Kong. “Objections are not about confronting China. Objections are about tactics—whether imposing aggressive tariffs work,” she wrote in a recent note to clients. “What’s next is not so much a trade war or even a cold war as the dawn of an ice age.”

Trump, who tweeted in March that “trade wars are good, and easy to win,” has at the very least shaken the status quo. No matter who succeeds Trump, “things won’t be back exactly to what it was like before he took office,” Mari Pangestu, the former Indonesian trade minister, writes in an email. Zhiwu Chen, director of the Asia Global Institute at the University of Hong Kong, predicts the emergence of “different trade blocs based on geography and values.” Economist Jim O’Neill, the chair of Chatham House who coined the term BRIC for Brazil, Russia, India, and China, says the rest of the world will not “necessarily suffer” from a pullback by the U.S. “because global trade has been increasingly shifting eastwards and southwards.” The Trans-Pacific Partnership will go on without the U.S.; the EU issued a pro-trade communique with China on July 16 and signed a free-trade deal with Japan a day later.

Whether Trump succeeds in imprinting his nationalistic agenda on the world depends in part on how many years he gets to spend in the White House. “If four, I think many of these slights will be mostly forgotten. Eight, no,” wrote Nye, the Harvard political scientist. Deborah Elms, executive director of the Asian Trade Centre, a consulting firm in Singapore, agrees: “If Trump stays in office for six [more] years, it will be much harder for other countries to manage the chaos in the interim.”

What’s instructive for today is how the U.S. extracted itself from the beggar-thy-neighbor spiral that started with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 and helped deepen the Great Depression. President Franklin Roosevelt lobbied for and got the Reciprocal Trade Agreement Act of 1934, in which Congress ceded some authority over international commerce to the president, empowering him to negotiate tariff reductions that Congress wouldn’t or couldn’t do itself. (Now, ironically, it’s the president who’s more protectionist than Congress.)

To Dartmouth College economist Douglas Irwin, a historian of free trade, one lesson of the 1930s is that “it’s not as easy to snap back as you think” from a trade war. Executive orders by Trump, such as the steel and aluminum tariffs, would be easiest for the next president to undo, he says, but withdrawal from a treaty such as the North American Free Trade Agreement would be considerably harder to reverse. Stickiest of all to turn around could be countermeasures by the likes of China. Progress in getting China to open its market to U.S. goods and services has been painfully slow. If China puts back nontariff hurdles in retaliation for U.S. tariffs, they may remain there for a long time because there are strong domestic constituencies for keeping them, Irwin says.

One reason Trump is able to get a lot of political mileage out of pugnacity toward trading partners is that the public’s understanding of free trade is fuzzy and support for it is soft. In the U.S., EU, Canada, and Mexico, half or more of the public endorses free-trade agreements—but even higher percentages in most of the countries say their country should protect its economy more strongly against foreign rivals, according to polling by Oxford Economics, Bertelsmann Stiftung, and YouGov Plc. To many people, “protectionism” isn’t a dirty word.

“The new narrative that’s emerged is one in which people think, ‘Our country’s problems are caused by behavior elsewhere,’ ” says Stephen King, senior economic adviser to HSBC Bank Plc. It’s easier to blame foreigners than to improve technology, education, and social mobility, because those are generation-long fixes, he says. “The difficulty you have as a politician is saying to people, ‘Be patient. Your children will be OK. But you won’t be,’ ” King says. He adds: “If it turns out that the U.S. economy does OK despite Trump walking away from historic commitments, it may be that the idea of an isolationist U.S., a separate U.S., takes hold beyond the traditional Trump supporter.” That would be a victory for Donald Trump, though perhaps not for the country he leads. —With Enda Curran and Jill Ward

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Howard Chua-Eoan at hchuaeoan@bloomberg.net, Eric Gelman

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.