Trump Picked His Perfect Education Secretary in Betsy DeVos

Trump Picked His Perfect Education Secretary in Betsy DeVos

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For all the years since Jimmy Carter picked Shirley Hufstedler in 1979 to be the first holder of the title, it’s been a tradition for the U.S. education secretary to address the annual gathering of the hundreds of journalists covering their department. Two years ago, Betsy DeVos, who’d recently been confirmed as President Donald Trump’s education secretary, turned down an invitation from the Education Writers Association. The next year she did so again, raising the possibility that she might be the first person with the job to snub the organization altogether in almost 40 years.

So the association’s members were excited when DeVos agreed to appear this year. What would their reluctant keynote speaker say? The tables in the ballroom on Baltimore’s inner harbor quickly filled with journalists eager to find out. The slim 61-year-old walked onstage wearing a light blue pantsuit, sparkling gold heels, and a forced smile. “The simple truth is,” DeVos said, sighing, “I never imagined I’d be a focus of your coverage. I don’t enjoy the publicity that comes with my position. I don’t love being up on stage or any kind of platform.” She gave her audience a plaintive look. “I am an introvert,” she said, placing her hand on her heart. Then she became defiant: “And as much as many in the media use my name as clickbait or try to make it all about me, it’s not.”

Once she was finished, DeVos took a seat onstage, leaning back in her chair as if she wished she could disappear rather than take questions from Erica Green, an education reporter for the New York Times. However, Green was gracious, as were most of the audience members who asked questions. Contrary to her reputation as someone who can be befuddled in public, DeVos fielded them all. An underperforming voucher program in Louisiana? She didn’t think much of it either. A proposal in a Tennessee education bill targeting undocumented students? She was pretty sure it didn’t wind up in the final version, so what was there to say?

There’s something mildly disingenuous about DeVos’s contention that she’s been the subject of undue scrutiny. She came to Washington in 2017 to serve Trump, who had agreed to pay $25 million the previous winter to settle claims that his namesake for-profit university bilked students. For decades, DeVos has promoted what she refers to as “school choice,” arguing that parents should be able to decide which school their children attend—with the government providing subsidies in the form of vouchers if they select a private one. Small wonder she has encountered opposition not just from Democrats and their teachers’ union allies, but also Republicans in rural states where traditional public schools are often the sole option.

DeVos hasn’t been the best advocate for her policies, either. She’s made some spectacular gaffes since entering public life, starting with her difficult confirmation hearing, in which she seemed perplexed about federal education law. The awkwardness continued into her early months at the department, when she called the nation’s historically black colleges and universities “real pioneers when it comes to school choice” (she has since acknowledged that her phrasing left something to be desired) and refused, in a House Committee on Appropriations hearing, to say if she would prevent federal funds from flowing to private schools if they discriminated against African-American or LGBT students. (Elizabeth Hill, DeVos’s spokeswoman, says her boss believes that any school receiving federal funds must follow civil rights laws.) DeVos hadn’t been in office for a year before a Huffington Post/YouGov poll showed more Americans had a “strongly unfavorable” opinion of her than of any other Trump administration cabinet member at the time. She’s also had to weather what former White House aides and people close to Trump now describe as the president’s indifference. Several say they’ve never heard him mention her name, though that might not be the worst thing in the Trump White House. Hill says DeVos can get a meeting with Trump anytime she wants.

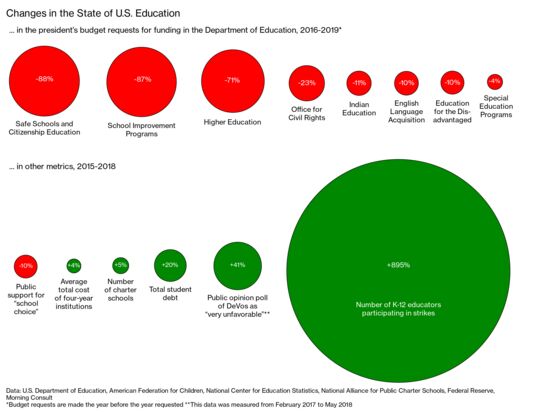

The embarrassments have continued. In March she attracted bipartisan ire when she publicly advocated eliminating funding for the Special Olympics, only to backtrack and say that she’d always opposed the cut after Trump casually overruled her. Some in the school reform movement have had enough of the drama at the department. Michael Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a conservative education think tank, says regretfully that DeVos should step down because she’s damaging her own cause: “She’s so unpopular that she’s making it harder for education reformers at the state and local level.”

Yet DeVos has been surprisingly effective on one front, and it could change the U.S. education landscape for decades. In early May she was feted by the conservative Manhattan Institute in New York, where she reeled off a list of the Obama-era initiatives she’d overturned or was in the process of reversing concerning civil rights and student protections. It was almost as if she were displaying a collection of scalps. “We’re breaking the stranglehold Washington has on America’s students, teachers, and schools, starting with all the social engineering from the previous administration,” she boasted. Outside, protesters all but called for her head. Inside the marble-columned banquet hall, listeners repeatedly interrupted her with applause.

Much has been written about DeVos’s privileged background: how she grew up in a tightly knit Dutch-American enclave in western Michigan and attended religious schools and a nearby college named after John Calvin, the 16th century theologian who believed in predestination; how her father, Edgar Prince, became wealthy by inventing the lighted automobile sun visor; how she married Dick DeVos, son of the late billionaire co-founder of the Amway direct-selling empire; and how together they’ve used their riches to advance conservative educational causes in Michigan.

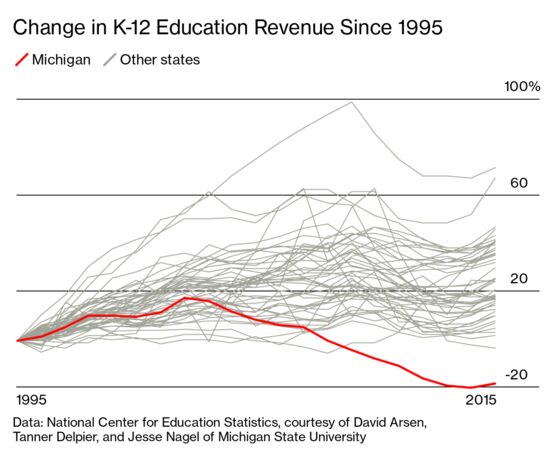

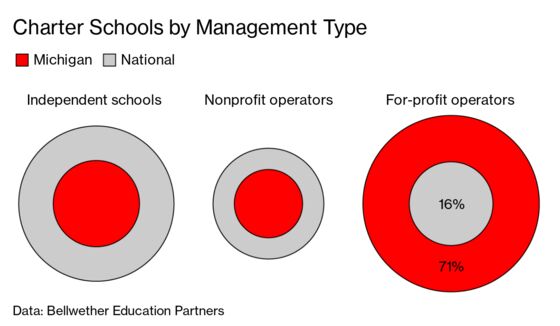

Somewhat less has been written about the results of such policies in her home state. In a study of federal data from 2003 to 2015, Brian Jacob, a professor of economics and public policy at the University of Michigan, found that the state’s fourth and fifth graders had lower growth rates in math and reading scores than any of their peers around the country. He says many things could have contributed to this, including poverty, but DeVos’s initiatives, like promoting a lightly regulated charter sector with a large number of schools run by for-profit companies, haven’t helped. “Personally, I think there is evidence that the very deregulated form of private school involvement hasn’t been good for education in Michigan,” Jacob says. Hill responds that another study shows charters in Michigan outperforming traditional public schools, and that the state is lagging because it hasn’t fully embraced her boss’s policies.

Undaunted by Michigan’s shortcomings—or, some would say, oblivious to them—DeVos co-founded the American Federation for Children in 2009, a dark-money-enabled advocacy group that she chaired until 2016. During this time, says John Schilling, the federation’s president, DeVos worked with sympathetic former Republican governors, including Indiana’s Mike Pence and Wisconsin’s Scott Walker, to double the number of states with private school choice programs. According to the federation, 26 states and the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico now offer some form of private school tuition supports, such as vouchers and tax credits.

Given her conservative allegiances and oft-stated distrust of government, DeVos might seem like someone who naturally would have gravitated in 2016 to Republican presidential candidate Trump, who the previous year devoted a chapter in his book Crippled America: How to Make America Great Again to scorning the Department of Education, calling it “a disaster.” But at the Republican National Convention that year, DeVos expressed qualms about what she described as Trump’s “erraticisms.” “A lot of the things he’s said are troubling,” she told Bloomberg Businessweek at the time, “and I don’t think reflective of the kind of leadership and temperament it takes to be president.”

Yet after Trump’s victory, DeVos allies such as Vice President-elect Pence promoted her as a candidate for education secretary. In late November he nominated DeVos for the job, calling her “brilliant.” She would have little power over K-12 education: The federal government provides only 7% of the $818 billion spent annually for U.S. elementary and secondary education. But the position gives DeVos a national pulpit from which to evangelize about school choice. And it casts a longer shadow over the higher education sphere, overseeing the $1.4 trillion federal student loan program. “When the opportunity arose, I couldn’t say no,” she said earlier this year at a meeting of the Conference for Christian Colleges & Universities in Washington, D.C.

Having never served in government as an elected official, or an appointed one for that matter, DeVos struggled in her new role. Her confirmation hearing in January 2017 was a circus-like proceeding, with Democratic senators pouncing on her mistakes and raising questions about her fitness for the job. It was unclear whether the nominee herself grasped that not just her nomination, but the viability of Trump’s presidency, was at stake. “She was very timid and polite and respectful to the panel,” says Matt Frendewey, a former senior adviser to DeVos. “Four or five years ago, that would have been fine. Unfortunately, in this environment, you can’t do that.” DeVos has also blamed her transition team for doing a lousy job of preparing her. (She declined to comment for this story.)

In private, her new employees found her more knowledgeable than they’d expected, if somewhat blinkered in her perspective. “She really does care about helping kids in this nation,” says a former high-level official at the department, who spoke on condition of anonymity because she was no longer there. “She just has some very specific ideas about how to accomplish that.” However, in public, DeVos continued to flounder. Protesters greeted her when she visited schools, beginning with her first trip to a public one in February 2017. Demonstrators surrounded DeVos’s SUV and tried to keep her from entering Jefferson Middle School Academy in Washington, D.C., chanting “Go home!” and “Shame, shame, shame!”

Once inside, DeVos impressed teachers. “It seemed like she was for public education,” says Ashley Cobb, an eighth grade math teacher and the local union representative. The next day, though, DeVos obliterated whatever goodwill she’d earned by telling conservative columnist Cal Thomas that the school’s teachers had been lulled into passivity by the government’s “top-down” approach to education policy: “They’re waiting to be told what they have to do, and that’s not going to bring success to an individual child.” Cobb says DeVos’s remarks infuriated instructors, many of whom have master’s degrees. “We had a community meeting to let the students know that was unacceptable,” she says. “No one is going to come into our house and badmouth us, especially when it’s inaccurate.”

The following month, DeVos met with LGBT leaders concerned about her decision to withdraw an Obama administration letter to school districts advising them to let transgender students use the bathroom conforming to their gender identity. Mara Keisling, executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality, was there with several parents of transgender students. She says one of them argued that she should have a choice in how her child was treated at school. “The secretary just lit up and said, ‘Well, that reminds me, when my choice proposals come out, I hope that’s something we can all get together on and you can support me on,’ ” Keisling recalls. “It was actually an astounding moment.”

DeVos also tried to woo American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten, which was never going to be easy. In April 2017, the two made a much-heralded trip to Van Wert, Ohio, to visit the public schools there. “She’s a very proper lady,” Weingarten says. “She was interested in the kids.” However, Weingarten says she resisted the secretary’s attempts to turn things into dewy photo opportunities. “She wanted to plant a tree together,” Weingarten remembers. “I’m like, Well, we don’t really have a relationship. Why would we plant a tree together?” (Representatives for DeVos say they don’t recall some of the interactions described to Bloomberg Businessweek, including this one.) The two of them, predictably, have gone on to become sparring partners, with Weingarten calling DeVos a tool of special interests and DeVos labeling Weingarten a richly paid union boss.

By the end of her first year, DeVos had adopted a defensive crouch when dealing with her critics and the press. Her congressional appearances were rare, and she’d often repeat the same innocuous responses when pressed by Democrats—how she cared about all students and was just following the law—who, in fairness to DeVos, often seemed more intent on tripping her up than hearing what she had to say. In her first year, she granted interviews to mainstream media outlets such as Politico and the New York Times. Then came her disastrous March 2018 appearance on 60 Minutes, in which she seemed confused about Michigan’s educational progress or lack thereof. The White House noticed. A presidential aide called one of DeVos’s people to say that Trump thought the interview a catastrophe, says one person familiar with the situation. (Hill, DeVos’s spokeswoman, says, “I did not receive that call.”) After that, DeVos tended to talk to friendlier media such as Fox News and the Weekly Standard, along with local reporters in places like Benton, Ky., and Tulsa, who might not grill her like their Washington counterparts. Reporters who run into her on Capitol Hill these days say she just smiles and keeps walking when they ask about departmental business.

Her efforts to promote school choice on Capitol Hill didn’t fare much better. Her allies talked about including a tax credit to benefit privately funded local school vouchers in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, but it never made it into the final bill. DeVos settled for a weaker measure letting parents use money in their tax-advantaged college savings accounts for private school. She herself concedes this benefits only families who already have enough money for tuition, not the lower-income ones whom she frequently argues need access to private education the most.

Earlier this year, DeVos held a press conference extolling legislation to create a $5 billion-a-year tax credit to support a variety of locally run school choice initiatives, including subsidized private school. It doesn’t seem to be going anywhere: House Democrats are dead set against it. So far, Trump’s support hasn’t exactly been full-throated, either. He seemed disinterested when DeVos briefed him on it, says a source familiar with the meeting, adding that this was indicative of his lack of interest in education, not a knock on DeVos. Hill, her spokeswoman, disputes this, saying Trump personally signed off on it. “The first thing he asks [DeVos] almost every time they talk is, ‘How are we coming on school choice?,’ ” she says.

Still, there was much DeVos could do within the department that didn’t require legislation. Under Obama the department had taken an expansive approach to protecting minorities, campus sexual assault victims, and students who had suffered at the hands of unscrupulous for-profit college operators. It was not without controversy and had a distinct social justice underpinning. “Every one of those issues, it was always about trying to fight for the powerless, those that were being hurt by the system,” says Arne Duncan, Obama’s longest-serving education secretary.

To hear DeVos tell it, the Obama people had turned the department into a lab for dubious social and legal experimentation. She was particularly galled by the administration’s habit of advancing its policies by sending guidance letters to schools rather than going through the formal regulation process, which would have required the department to seek public comment.

These letters were much easier to rescind than actual rules, though, and soon after DeVos arrived, she began doing so. Most notably, she pulled back a letter advising colleges to handle sexual assault cases by adopting a lower standard of evidence favoring accusers. It had been welcomed by survivors’ rights groups, but criticized by skeptics on both the right and the left who argued it had been applied without regard to the rights of the accused. DeVos did the same in 2018 with a letter warning schools that they would face civil rights investigations if they disciplined minority students at higher rates than whites, regardless of whether overt racial bias could be proven.

It seemed harder for her to justify her equally zealous unraveling of the Obama administration’s efforts to rein in the for-profit college industry. Naturally, DeVos, who told an audience in 2015 that “government really sucks,” has long been interested in free-market educational alternatives, but for-profit colleges have been plagued by scandal. A Senate investigation in 2012 detailed how many of the industry’s top chains, which relied on federal dollars, including student loans and Pell Grants, for the bulk of their income had used boiler room tactics to recruit lower-income students. Some also misrepresented their graduation rates and their ability to place pupils in jobs lucrative enough for them to pay off their debt. The fly-by-night nature of some of the largest players became evident before the end of Obama’s second term when Corinthian Colleges Inc. and ITT Educational Services Inc. went bankrupt, stranding more than 50,000 students without degrees.

The Obama administration responded with a number of measures, most notably drawing up the “borrower defense” regulation in 2016, which automatically forgave loans for students who had attended imploding schools if they hadn’t enrolled in more stable degree-granting institutions within three years. The regulation also banned schools from protecting themselves by requiring students to sign mandatory arbitration agreements and class-action lawsuit waivers as a condition of enrollment. “It’s not like this just came out of nowhere,” says Ben Miller, a former senior policy adviser at the department under Obama. “All these things were driven by real, documented problems and abuses.”

The Obama-era department also tried to wake up the nation’s 53 accrediting agencies, which serve as gatekeepers for the student loan program. Accreditors were supposed to ensure that colleges provided students with decent educations, but they had a history of coddling schools. “For the most part, accrediting agencies are the watchdogs that don’t bark,” Duncan said in a 2015 speech. The next year, the department withdrew its recognition of the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges & Schools, or ACICS, which had overseen schools run by ill-starred Corinthian and ITT Educational.

To DeVos, however, it was the department that had acted abusively, impeding innovation in the sector, and she surrounded herself with former for-profit college executives who were likely to agree. One of these was Robert Eitel, a DeVos senior counselor and an ex-vice president for regulatory services at Bridgepoint Education Inc., a company that the 2012 Senate report noted enjoyed a 30% profit margin even though 63% of its bachelor’s degree candidates failed to graduate. He was joined by Diane Auer Jones, DeVos’s principal deputy undersecretary, who had done a stint as a senior regulatory affairs officer at Career Education Corp. from 2010 to 2015, a time during which its chief executive officer resigned after the company admitted to falsifying career placement data, according to the Senate report. (A department spokesperson says that Eitel has recused himself from any decisions involving Bridgepoint, now known as Zovio, and that it was Jones who alerted the department about her former employer’s “job placement irregularities.”)

In her early months, DeVos put borrower defense on hold just before it was scheduled to go into effect and began crafting a more industry-friendly rule that, at least in an early version, would have done away with automatic loan repayment waivers, allowed schools to reinstate arbitration and class action stipulations, and required students to prove that their college has intentionally defrauded them. In a May interview in Washington, Jones contended that the final rule should be fairer to students and colleges. “We had concerns about due process rights,” she said, as two public-relations people sat on either side of her peering at their phones. The department’s efforts have been hampered by legal challenges, but Jones said she was confident that the new regulation would be finalized by November. Meanwhile, the department revealed earlier this year that it had a backlog of almost 160,000 unfulfilled borrower defense claims, prompting Democrats in Congress to accuse DeVos of slow-walking them. (Jones said this isn’t true.)

Meanwhile, DeVos stunned career employees in November by restoring the department’s recognition of ACICS. The department had to reconsider the decision, she said, because ACICS had successfully challenged the previous administration’s decision in court, saying it had failed to fully review tens of thousands of documents. Two weeks after ACICS was back in the department’s good graces, there was another catastrophe: The Education Corporation of America, a large for-profit chain with schools under ACICS’s purview, said it was going out of business, leaving nearly 20,000 students out in the cold. (Both Jones and ACICS President Michelle Edwards say there’s little the department or the accreditor could have done to prevent this.)

The department’s career employees are used to pendulum swings with new administrations, but not to anything like this. Nate Bailey, DeVos’s chief of staff, says that reports of the department’s employees’ dissatisfaction have been “grossly overstated.” Even so, between late December 2016 and the end of September 2018, 16% of DeVos’s staff had left, giving her department the highest staff depletion rate of any Trump cabinet-level agency. Current and former career staff members say discontent at the agency has never been higher.

Unlike some public schools and Capitol Hill, the January meeting of the Council for Christian Colleges & Universities was a setting where DeVos clearly felt at ease, even as she was pushed up the center aisle in a wheelchair. An aide positioned her next to Shirley Hoogstra, the council’s president, who settled into a green chair. DeVos explained that she was recently in a bike accident and broke her pelvis and her hip socket.

“Ooh, ouch,” Hoogstra said. She proceeded to tell DeVos that she was a role model to students in the room, and pursued a friendly line of questioning. “What have you found satisfying in your role as secretary?” she asked.

DeVos talked about her efforts to revamp accreditation rules and get rid of those Obama guidance letters, which she called “the bane of a lot of our existences.” She gave her host a knowing look.

“I’d like you to tell the students in the room about tackling big endeavors when you are going to get criticized and praised,” Hoogstra said.

DeVos has been attacked far more than she’s been lauded, but her response suggested that she doesn’t feel the need to answer to anyone, at least not in this world. She spoke nostalgically about her early years in religious schools. “I always go back to the fact that in my view there’s an audience that I play to,” DeVos said. “It’s just an audience of one. If I can keep that perspective at all times…”

“That’s the true North Star,” Hoogstra said.

“I think there’s no doubt that every day I’m regularly called,” DeVos said. “I refer often to Micah 6, verse 8. ‘What does God expect of me? To seek justice, love mercy and walk humbly with him.’ That’s a refrain that never leaves me.” —With Jennifer Jacobs, Josh Eidelson, and Emily Wilkins

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.