The Guy Who Spent $30 Million Building Trump’s Wall Is Looking for Buyers

The Guy Who Spent $30 Million Building Trump’s Wall Is Looking for Buyers

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- To get to Tommy Fisher’s private border wall in Texas, I drive south from the city of McAllen, then west on Military Road, past a chunk of redundant, abandoned federal border wall, and from there onto a dirt path through a sugar cane farm down to the Rio Grande. When I arrive, Fisher is waiting, wearing a Western-style plaid shirt, wraparound sunglasses, and a mesh baseball cap featuring his company’s logo. He’s 51 years old, with an ursine build and a disarmingly gentle voice.

By trade a builder of more prosaic infrastructure, such as dams and freeways, Fisher greets me by launching into a baffling sermon on his wall’s technical specifications. Mostly what I perceive is that we’re at its very edge, meaning we could theoretically walk around it and swim 100 yards to Mexico. Across the river, near the city of Reynosa, which has lately been wracked by unusually intense cartel violence, is a park with wooden docks and straw-roofed gazebos. Beyond the park, according to Fisher, is at least one cartel stash house, where drugs or people are stowed before being smuggled to America. As I poke around, Fisher says, “Make yourself at home.”

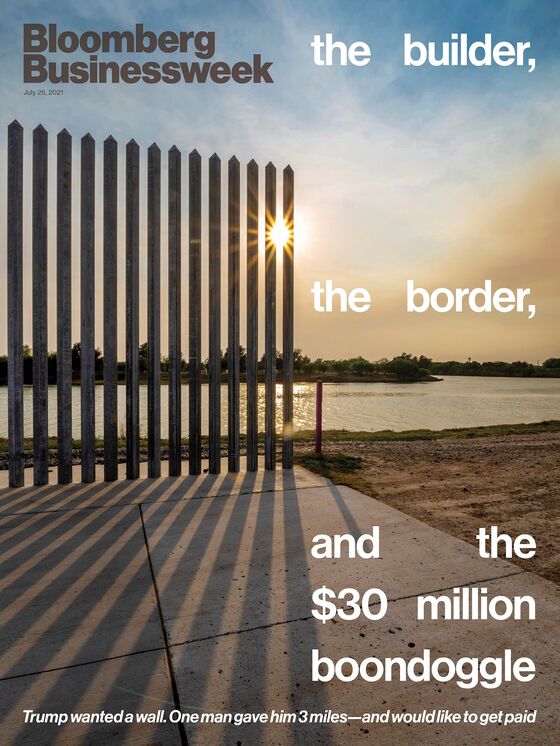

There are two private-sector border walls attempting to separate Mexico from the U.S., and Fisher Sand & Gravel Co. has built them both. The first, erected in the summer of 2019, is nestled in a mountainous half-mile stretch of New Mexico. The second—this one—is more ambitious. Completed last year, it’s about a 90-minute drive from the Gulf of Mexico, under the low, heavy skies of South Texas’ Rio Grande Valley. The structure is 3 miles long, hugging a severe bend in the river, and consists of roughly 15,000 18-foot-tall gray steel bollards, spaced 5 inches apart and set in a wide concrete foundation. (In this sense it’s more like a fence, but for simplicity’s sake I’ll mainly call it a wall.) Up close, one can easily see between the bollards. From a distance they appear to be a contiguous, glinting slab of sheet metal.

Fisher continues pummeling me with information about his creation—“galvanized steel,” “modified spread footing”—sounding like a proud parent, or maybe an anxious student, at a science fair. “If I only did 1,000 or 2,000 feet, everyone’s going to make fun,” he says. “No one can really make fun of this.”

He’s also invited Scott Hennen, a conservative radio host from his home state of North Dakota, to cover this late-March visit. Hennen is broadcasting live from a booth Fisher ordinarily uses to monitor security footage. It’s a couple of miles away, so we drive over to meet him. An entourage of Fisher’s contractors joins us for the tour.

Although Hennen’s state borders Canada, not Mexico, his callers are eager to discuss the surge of Central American migration that’s occurred early in the Biden era. Three days earlier, former Trump adviser Stephen Miller joined Hennen for an hourlong segment on the issue. Wearing a headset, wiry and in his mid-50s, Hennen walks in and out of the booth, monologuing. “We’re gonna talk to Tommy Fisher, who is North Dakota-born-and-bred, which is why he was able to build 3 miles of wall in 30 days,” he says. He reads a text message from a listener about the specter of Covid-positive migrants and runs with the point, complaining that they’re being beckoned into the country while idiotic but basically innocent American spring breakers are demonized for partying.

Fisher stands awkwardly outside the booth, hands in pockets. He’s conservative, too, but Midwest-nice about it and not prone to rants. Eventually, Hennen turns to him. “We are looking at a project that you did, on your own dime,” he says. “Why did you do this?”

For ages, Fisher has dreamed of building an epic piece of infrastructure. A decade ago, Nevada hired him to construct what’s apparently the longest cathedral arch bridge in the world, but it didn’t make him a household name. When Donald Trump ran for president, promising to wall off the entire 1,954-mile southern border, Fisher sensed an opportunity. “I was like, ‘This would be really fun. This would be a project that would be remembered, like the Hoover Dam,’ ” he says. “Today the Hoover Dam is the cheapest electricity you can find in the U.S.—anywhere. And, you know, they took a lot of heat, too.”

In the first few years after the 2016 election, Fisher spent more than $100,000 on lobbying in Washington and mounted a media blitz, claiming on Newsmax and Fox News that his company could build a wall faster and cheaper than anyone else, thanks to vertical integration that included doing its own land excavation and cement mixing. Fisher Sand & Gravel’s history with the government wasn’t pristine. In 2009 one of Fisher’s brothers had been sentenced to 37 months in prison for filing doctored tax returns on behalf of himself and the company, which paid $1.1 million to the IRS as part of a plea agreement. Separately, the company has racked up close to $1 million in fines for environmental, labor, and safety violations.

As he angled for wall contracts, Fisher quickly encountered the vagaries of the federal contracting process. A prototype he built in 2017 was rejected by the Department of Homeland Security, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers initially denied his bid to compete for the contracts at all. But the cable news exposure helped him draw the attention of We Build the Wall (WBTW), a nonprofit founded by Brian Kolfage, an Iraq War veteran and triple amputee, and co-led by former Trump adviser Steve Bannon. The group, which sought to crowdfund border security, attracted a mix of true believers and attention hounds, among them immigration hawk Kris Kobach, who served as its general counsel, and former baseball player Curt Schilling, who sat on its board. Blocked from erecting Trump’s official wall, Fisher became the in-house builder for the ersatz private version.

In the spring of 2019, WBTW paid him $6.9 million to build its first barrier, the half-mile in New Mexico. Fisher used the gig to show off proprietary construction techniques, which he promoted with a drone-camera-filmed sizzle reel. By late 2019 he’d reached an agreement with a farmer named Lance Neuhaus to buy a 45-acre strip of riverfront land near McAllen, on which he would build a second WBTW-funded structure. Partly, Neuhaus says, he sold because Fisher offered him a good price. He also thought the structure might stem what he says was a daily flow of migrants onto his farm. The wall would be built closer to the Rio Grande than any existing federal barrier.

WBTW sent Fisher an initial payment of $1.5 million, for what he says ended up being a $30 million job. He ordered a bunch of steel and started clearing vegetation. But the project was soon overshadowed by the group’s antics. WBTW deployed a kind of human mascot known as Foreman Mike to patrol the site in a hard hat and scout for immigrants, while Kolfage sent out increasingly aggressive tweets about the National Butterfly Center, a nearby wildlife preserve whose executive director, Marianna Treviño-Wright, vocally opposed border wall construction. Kolfage called the center a “big business” that “openly supports illegal immigration and sex trafficking of women and children.” (Treviño-Wright, for her part, says she considers WBTW a “ Cambridge Analytica-style psy-op.” She has also filed suit against Kolfage for defamation. His lawyer didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

Eventually, Fisher got the sense that Bannon’s gang wasn’t necessarily committed to another wall. After he called WBTW for another payment and it never came, he kicked Foreman Mike off the site, parted ways with the organization, and started funding the project with company money. Several months later, in August 2020, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York indicted Bannon, Kolfage, and two other WBTW figures for allegedly enriching themselves with money Kolfage had assured donors—mostly ordinary cable-news-watching types—would go to wall construction. Before Trump left office, he issued a preemptive pardon that appears to have shielded Bannon from prosecution, rendering his not-guilty plea moot. Kolfage and the other co-defendants, who also pleaded not guilty, are set to go to trial in November.

Fisher wasn’t implicated—he was just building wall. But that caused trouble of its own. For one, he was sued by the National Butterfly Center, which argued his wall could end up diverting water and debris onto its land in the event of a flood. And as if the notion of a border wall drowning butterflies weren’t bad enough, he was also sued by an obscure government agency, the U.S. International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC), which argued diverted water could end up displacing the U.S.-Mexico borderline.

Fisher contested the suits, confident that when construction was complete, the U.S. government would want to buy what he was calling the “Lamborghini” of walls. The bureaucrats may have sniffed at his earlier building proposals, but his peacocking for the White House was starting to pay off. According to the Washington Post, Trump and his adviser and son-in-law, Jared Kushner, had begun urging the Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to give wall contracts to the guy they recognized from Fox News. In the last year of Trump’s term, even as federal prosecutors were hovering around WBTW, Fisher Sand & Gravel was awarded $2.5 billion to build 135 miles’ worth of federal wall sections near Yuma and Nogales in Arizona and El Paso and Laredo in Texas. (Following a request by a Democratic congressman, the U.S. Department of Defense is conducting an audit to determine whether one of the contract awards was politically motivated; in a statement, the Army Corps of Engineers said it goes to “great lengths to ensure the integrity of our contracting process.”)

Then Joe Biden was elected president, and the odds that America would buy an unsanctioned border wall associated with an allegedly criminal enterprise helmed by Steve Bannon dropped significantly. Once in office, Biden halted construction of Trump’s wall, too, freezing the eleventh-hour building frenzy that had taken place in the runup to Inauguration Day. Fisher’s private 3-mile wall seemed destined to live on as a monument to the nativism, opportunism, and general half-assery of the Trump era.

And yet, Fisher remains eager to promote it, for one very un-ignorable reason: The border crisis isn’t going away. In June, 188,829 people were apprehended at the southern frontier, the highest monthly total in at least two decades and a roughly sixfold increase from the year before. Makeshift government shelters have overflowed, leaving migrants, many of them minors from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, living in cramped, abominable conditions during a pandemic. Throughout the spring, as U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) processed the influx of children and families applying for asylum, an estimated 1,000 adults a day were slipping across the border freely, the highest number agency officials could recall.

While the drivers of the surge were long-standing problems in migrants’ home countries, many recent arrivals said they’d come now because they’d understood Biden would be more welcoming than Trump. Despite the broad popularity of his heady domestic agenda, Biden was suddenly polling negatively on immigration and fighting the perception of even some in his own party, such as U.S. Representative Henry Cuellar of Texas, that he didn’t have control of the border. “Do not come. Do not come,” said Vice President Kamala Harris, the administration’s point person on the immigration surge, during a June visit to Guatemala. “The United States will continue to enforce our laws and secure our border.”

Republicans have pounced, crowing that Biden is pulling the plug on wall-building at exactly the wrong time. And Fisher would argue he’s pulling the plug in the wrong place. The Rio Grande Valley, where his 3-mile wall sits, is by far the most highly trafficked of the nine Southwest sectors policed by CBP. Of the 79,519 unaccompanied minors the Border Patrol apprehended in the first six months of this year, 40,507 entered via the valley, up from about 3,800 in the first half of 2020. Walking the banks of the river near Fisher’s wall, I find ample evidence of recent border crossings: a Motorola flip phone, a 20-peso bill, a Winnie the Pooh towel, a small fridge that may have been used as a raft.

With the We Build the Wall trial looming, Fisher’s critics still tend to associate his fence with the group. “I think it was some racist front scheme,” says Ricky Garza, a McAllen-based attorney at the Texas Civil Rights Project, which represents landowners in border disputes with the government. Ryan Patrick, the now former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Texas who led the IBWC case, has publicly described Fisher’s wall as a “scam,” a “vanity project,” and “beyond vaporware.”

From this vantage point, Fisher appears to have erected two small walls nobody asked for while leveraging his connection with Bannon & Co. to build a lavish, taxpayer-funded political dog whistle. When I put this critique to him, he looks wounded. He says his procurement of federal contracts had nothing to do with his private wall. In fact, in his telling, what he’s built in Texas is superior to what Trump contracted him to do. It’s proof of concept for something that’s never quite been attempted in the U.S. And if scaled up, he argues, it would solve a problem the government hasn’t been able to crack.

Fisher concludes his interview with Hennen, and we drive back through the sugar cane farm until we reach the steel border fence I’d passed on Military Road. Hennen heads into an abandoned shed to record a Facebook Live hit. Fisher, the contractors, and I drive up for a closer look. This is Trump-era federal wall, built on a dirt levee by a rival contractor based out of Galveston, Texas. Nobody’s here; work stopped abruptly on Jan. 20, the day Biden issued his moratorium. The structure was supposed to be part of a 13-mile system of border barriers, but construction didn’t start until 2020, and it’s only a couple thousand feet long. Fisher brought me here to highlight the superiority of his product, which we can see about a mile to the south. “You’re a BP agent,” says Tad Dyer, Fisher’s landscaping guy. “Do you want to patrol a 150-foot-wide strip? Or do you want to patrol 2,000 yards?” He’s referring to the gap between wall and river. Fisher’s wall is right up close. This one is nowhere near.

Federal wall in the Rio Grande Valley is largely a patchwork of rust-colored 18-foot-tall bollard fence, erected in the early Obama years, and rust-colored 30-foot-tall bollard fence, erected in the late Trump years. Sections stop and start suddenly, with gaps wherever the government couldn’t build. There’s no official map documenting it, and recently constructed stretches haven’t shown up on Google Maps’ satellite view yet. As we drive from one ghostly swath of the wall to the next, it becomes evident that its most salient feature is how little of it the federal government has managed to build.

There’s a reason for this. The U.S.-Mexico border is in fact more like two borders. West of El Paso, it runs 699 miles through the deserts and mountains of New Mexico, Arizona, and California before splashing into the Pacific Ocean. Almost all of that borderland is owned by the federal government, anchored by a 60-foot-wide strip President Theodore Roosevelt secured in 1907 to patrol for smugglers. Wall-building there is legally straightforward. East of El Paso lies 1,255 miles of Texas border, spanning a number of climates and terrains, separated from Mexico by the natural barrier of the Rio Grande. Almost all of this land is privately owned, divided into countless weirdly shaped parcels: ranches, farms, backyards. (The reasons for this are rather byzantine and can be traced to the terms of the Union’s 1845 annexation of Texas.) To build here, the government must either persuade landowners to lease part of their property or else seize it via eminent domain. Either way, it’s hard.

Prior to the 1990s, the little fencing that existed along the U.S.-Mexico border was made out of flimsy chain-link, often serving to pen in roaming livestock. In response to increasing illegal migration by Mexican job seekers, the U.S. government in 1993 erected its first bona fide border wall, between Tijuana and San Diego County, then the busiest point of entry. Jerry-rigged out of corrugated steel helicopter landing mats used in the Vietnam and Gulf wars, it was 10 feet tall and 14 miles long.

The wall worked, in the sense that apprehensions declined significantly in San Diego. The wall also didn’t work, in the sense that it funneled traffic eastward. The Clinton administration ended up building more landing-mat wall in the Arizona cities of Naco and Nogales, while deploying “human walls” of border agents elsewhere to stand sentry. The result, once again, was that migration patterns shifted to more remote crossings. In the decade that followed, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, immigration-related deaths doubled, as migrants succumbed to thirst and exposure in Mexico’s Sonoran Desert.

The George W. Bush and Obama administrations increased total fencing to 654 miles, about half of it tall steel barriers designed to prevent pedestrian crossings and half of it shorter barricades to rebuff vehicles. Between the two administrations, basically all the borderland of California, Arizona, and New Mexico got cordoned off with some kind of deterrent structure. In those three states, apprehensions plummeted. But in Texas, despite hundreds of federal attempts to seize land, virtually nothing was built.

Absurdly, the situation repeated itself during the Trump administration. Having staked his political identity on building a wall, Trump proceeded to refortify everything west of Texas, mostly commissioning taller, sturdier versions of what Bush and Obama had already built. By January 2021 Trump’s administration had erected 452 miles of wall, 372 of which replaced or renovated existing structures. For this it allocated $15 billion, compared with the $2.5 billion spent by the Bush and Obama administrations combined. In Texas, predictably, the border stayed stubbornly unwalled: Of 110 miles Trump pledged to build in the Rio Grande Valley, he managed only 17.

It’s probably not a coincidence that the most highly trafficked border region is also among the very hardest to fence off. This challenge gave Fisher his opening. The government struggles to build in Texas not only because it doesn’t own the land, but also because its sales pitch to landowners is awful. The IBWC blocks border wall construction within the flood plain of the Rio Grande, typically forcing it to take place a mile or so inland, where it might bisect somebody’s property or hem it in from the north. Consider the Loops, a Brownsville farming family whose home is caught between Obama-era wall on one side and the Rio Grande on the other. To enter and exit, they must punch a code that opens an electronic gate in the wall. In January 2017 their home caught fire with their pets trapped inside. The fire department, needing to negotiate the gate, didn’t arrive in time, and the house was destroyed.

Fisher got around this problem by testing the federal government’s rules and sticking his bollards right on the Rio Grande. “You gotta put your border protection on the border,” he says, frequently. That, he figures, is the starting point for serious wall-building in Texas.

As much as Fisher believes in his private wall, what he really needs is for someone else to believe in it, and to believe in it enough to take it off his hands. That’s where publicity, he hopes, comes in. After our tour of the abandoned federal barriers, he tells me that to get the full wall experience I need to see his private one again at night. We lunch at a Mexican restaurant in a mall, head back to our respective hotels, and return a few hours later, at sundown. The weather is windy and cool, the atmosphere unnervingly hushed. The wall’s foundation doubles as a wide concrete road, illuminated by floodlights that turn on at sunset. Federal walls tend to lack such amenities, and he wants me to get a good look at them. Our vehicles trace the perimeter like stock cars on a track. We drive by a burning bush. One of us runs over a snake.

Before Fisher cleared the land, the banks were populated by a thick, tall, invasive species known as carrizo cane, which probably helped protect the banks from erosion but also made it easy for people to hide from the Border Patrol. The sugar cane farther inland has recently been harvested, too, giving much of the property a buzz-cut look. When we reach the end of the wall, a couple of Border Patrol agents are hanging out in their truck. Dyer, the landscape guy, mentioned to me earlier that Border Patrol sometimes comes here to nap. The two agents tell Fisher they’ve generally been apprehending someone here every other day.

Fisher opens a gate in the wall to get a better view of the river. Just to the north, a handful of Texas Army National Guard soldiers, deployed in support of the Border Patrol, are monitoring the Rio Grande in a Humvee. On the river a motorboat passes by, mounted with what appears to be a .30-caliber machine gun. “Rangers!” Fisher calls to the Texas Rangers on board. He gestures upriver, past some swaying palm trees. “This is always my favorite. Sort of peaceful,” he says. “All lit up.” The wall, he tells me, was designed to integrate with the landscape. He calls his bollards “silver trees.” Their pyramidal tops are a tribute to the Washington Monument.

Walls get a bad rap, in Fisher’s view. “I just think they gotta take the stigma out of the wall as a, I mean, you know what I’m saying, racist kind of thing?” he says. “It’s a border, it’s a barrier, that’s all it means.” Part of his attempt to destigmatize walls involves pitching his as, in essence, a family-friendly mixed-use property. Earlier he gave me a flash drive containing what’s surely a one-of-a-kind rendering: Mexico, the river, his wall—and a bike path. In the illustration, the concrete roadway is divided in two. On one side are bikers wearing helmets; on the other, green-and-white Border Patrol trucks.

Ideally, Fisher wouldn’t just sell off his wall—he’d expand it, charging $20 million per additional mile. Standing there that evening, he starts to dream. “Can you imagine if this was 50 to 100 miles, and this was a bike path you could use? Even if the Border Patrol was over here, minding their own business?” He dreams some more. “Texas could have the longest bike path anywhere in the world. Four hundred miles. Five hundred miles.”

I find it hard not to imagine an amended rendering that includes a Border Patrol officer chasing immigrants across the sugar cane field. Not to mention that, by the agency’s count, at least 203 people have died trying to cross the border illegally so far this year; in late 2019 the body of a man washed up yards away from Fisher’s construction crew, attached to empty plastic water bottles that hadn’t saved him from drowning. I suggest to Fisher that bike riders might find it hard to enjoy the great outdoors as they witness destitute Central American families rafting across the river. But he’s now dreaming even bigger, and he doesn’t seem to hear me. He imagines creating a gigantic athletic field on the nearby farmland. He could host competitions. “The best of Mexico would play the best of America.” The Border Games. He sounds serious.

For most Americans, the wall is a charged political symbol and a physical abstraction. For Fisher, it can seem like the opposite: a cool infrastructure project that just happens to separate the U.S. and Mexico. But although his North Dakota upbringing may not have steeped him in the nuances of Central American migration, he’s lived for over a decade in Tempe, Ariz., where his company has its southern headquarters, and he’s developed views. He’s certainly not in favor of open borders, though he often frames his opposition to illegal immigration by citing abuse that migrants suffer at the hands of cartel coyotes. “I really feel that if the border was done, people couldn’t exploit people from other countries,” he says.

At least to me, Fisher is pitching his wall in idealistic terms. To his potential buyers, he claims it’s just a superior product. For one thing, his wall doesn’t have the 5-foot-high “anti-climb” plate that graces recently built federal wall. These plates are supposed to make it harder for people to hike themselves up the bollards. But Fisher argues that they’re excellent anchors for makeshift grappling hooks and that, when the wind batters them, they shake the wall’s foundation. Other differences: His steel bollards have been coated with zinc to prevent rusting, and at 18 feet rather than 30, they pose less risk of serious injury if someone falls from the top. Then, of course, there are the border security perks offered by the cleared cane, the bright lights, the road for Border Patrol trucks, and—most important—the proximity to the river.

None of these virtues, nor the billions of dollars the Trump administration was planning to bestow on Fisher to build federal fencing, prevented the U.S. government from turning against his private wall. “I never got any pushback from the White House or the DOJ or anybody else,” says Patrick, the former U.S. attorney who sued on behalf of the IBWC. “Everybody was like, ‘This is stupid, this violates the law, go ahead.’ ”

In July 2020, several months after the suit was filed, reporters from ProPublica and the Texas Tribune commissioned hydrologists and engineers to analyze the wall. They concluded that riverbank erosion put it at serious risk of toppling. Trump evidently saw the article, tweeting that the wall had been built “to make me look bad.” (“I don’t believe he had all the facts,” Fisher says.) A month later a hurricane caused significant erosion of the banks, up to and under the concrete foundation. Treviño-Wright, the National Butterfly Center executive director, crawled underneath to demonstrate, tweeting out the photo evidence.

I’m not an engineer, but the soil around the base of the wall does feel disturbingly crumbly when I kick at it. Fisher says that his concrete is buttressed by steel rebar and that his erosion problem will disappear once the Bermuda grass he planted fully grows in and his sloped “golf course” riverbanks are lush.

At one point, Fisher tells me he heard that someone with the Army Corps of Engineers derided his wall as “toothpicks in concrete.”

“Toothpicks that don’t break,” he retorts. The Corps declined to comment.

While Fisher’s critics wrangle over whether his wall is primarily an object of exclusion or of pathetic ineffectiveness, some of its neighbors have an entirely different perspective. Across Military Road, north of the sugar cane farm, Al Parker and his wife have been living in the same house for about 25 years. Surrounded by thorny shrubs and low-hanging mesquite trees, the property is remote, with no neighbors on either side. When I meet him, Parker, who works as a maintenance manager in the oil industry, is wearing a camo hat and a work shirt with “Al” emblazoned above the breast. He starts telling me about the last time a migrant passed through his property. “My wife was sitting on the back porch, and a woman walked out of the brush in tears,” he says. “She’d been hiding in the brush for two days, and she was exhausted, and hungry, and thirsty. I fed her and got her some water and called BP.”

The point of the story isn’t the event itself, which Parker says has repeated itself thousands of times at the house. The point is how long ago it took place. “It went from three or four times a week, to now it’s every four months,” he says. “I mean, the activity has ceased. One day my wife and I are sitting at the table, and it’s one of those ‘exhale’ moments: You realize it’s been a month, we haven’t had anybody at the front door or traversing through the property.” The change came after Fisher’s wall went up.

I get a similar report from George Syer, a longtime local Border Patrol agent who retired last September. Syer had spent countless nights patrolling the farm’s 800 acres with his flashlight, trying to apprehend migrants who’d rafted onto the property. He says the crossings abated when Fisher’s wall was erected. On their own, he tells me, walls are inadequate. People can go over or around them. They can saw through them. There’s video of all of this on the internet. What they do is slow down and funnel foot traffic, easing the Border Patrol’s job. “What Fisher did is he mitigated all of the brush, he put up the wall. Now we have visibility, and we have control of the flow,” Syer says. “Once his fence was up, we were concentrating further up the river, where we didn’t have fence.”

Whatever the merits of Fisher’s wall, there is one factor, a recent change in immigration patterns, that can render its advantages moot—and can make it seem pointless to build any kind of barrier in Texas. The morning after we meet, Syer and I hop in a boat so he can show me the location of popular river crossings in relation to Fisher’s property. Toward the end of the ride, not far from the official U.S. port on the Anzalduas International Bridge, we see a smuggler unsteadily ferry almost 20 people, mostly women and young children, across the river on an inflatable green-and-yellow raft. No one appears to be wearing a life vest. On the bank on the Mexican side, off a well-trod dirt path, about 20 more people are waiting for the smuggler to return for them. When Syer and I disembark, we climb in his pickup and head to the levee-wall border fence, a combination of Obama-era and Trump-era construction, that the migrants are probably aiming for. He texts his ex-colleagues to tell them a small group is on its way to find them, in case a brush sensor hasn’t alerted them already.

And that’s the thing. Prior to 2014, illegal crossers tended to be Mexicans seeking to evade detection. The migration surges since then, including the last two big ones, in 2014 and 2019, have been driven by Central Americans, many fleeing poverty or gang violence and hoping to apply for asylum. Once these migrants disembark on the U.S. side of the Rio Grande, they aren’t trying to escape Border Patrol. They’re trying to be found.

Biden is expelling the majority of migrants, ostensibly for public-health reasons, as soon as they’re encountered by Customs and Border Protection, under a Covid-era policy instituted by the Trump administration. But unlike Trump, Biden is allowing all unaccompanied Central American minors and what’s amounted to roughly 80% of families to remain in the country while they seek asylum. While most of the new arrivals won’t technically qualify for it, the immigration courts are so backlogged—about 1.3 million cases were pending when Biden took office—that many applicants can live in the country for months or years awaiting a hearing.

Fisher’s barrier might be closer to the border than any other wall in Texas, but the 30-odd feet separating it from the Rio Grande is all an asylum-seeker needs. The irony of Fisher Sand & Gravel’s 3-mile wall, with its floodlights and freshly cleared carrizo cane, with its ambitions of bike lanes and sports fields, is that it isn’t so much thwarting immigrants as beckoning them.

For now, everything is in limbo. The IBWC is trying to get Fisher to fortify the riverbank or maybe modify the structure—and, if all else fails, remove the wall entirely. The commission’s and the National Butterfly Center’s cases have been joined, and a trial won’t take place until spring 2022 at the earliest. Meanwhile, the tax bill on the land has skyrocketed. The property has been reassessed at 100 times its previous value because of a county quirk that now classifies it as “commercial” rather than agricultural land. Fisher, who says he’s disputing the assessment, is on the hook.

His federal wall contracts are in limbo, too. While border wall construction is currently paused, it’s unclear if it will stay that way. In May the Biden administration announced that it was canceling wall-building contracts Trump paid for by diverting funds from the Department of Defense. But that still leaves all the suspended wall projects funded with $5 billion of Department of Homeland Security money. “I suspect there’s a plan being formulated,” says Garza, of the Texas Civil Rights Project. “The Biden administration will try to claim a win and say, ‘No more wall construction, but we’ll pivot to virtual walls: sensors, cameras, and roads.’ ”

When Biden’s moratorium was announced, Fisher had completed 79 of the 135 miles he’d been contracted to build. If Garza is right, it’s conceivable Fisher could keep working a couple of his jobs, build border infrastructure that’s more palatable to Democrats, and recoup some of the cash he spent on his private wall.

There’s still hope for the big score, too. When we were at the border, Hennen, the radio host, helpfully floated the idea of finding 20 patriotic billionaires to pay $1 million each to help sustain the private wall, but that scheme is thus far 20 billionaires short. Instead, Fisher has been traipsing around Texas, pitching his barrier as part of a larger statewide system. On the strength of his silver-tree prototype, he tells me, he’s reached handshake agreements with 15 or so landowners to build on their properties. He says he’s also enlisted former CBP Commissioner Mark Morgan and former Immigration and Customs Enforcement Director Thomas Homan as paid consultants in hopes they’ll have influence with Texas Governor Greg Abbott. (Morgan and Homan didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

In June, Fisher was handed a potential lifeline when Abbott announced that Texas was getting into the wall-building business. Whether or not the state hires Fisher or builds anything at all, at least one element of its operation will be familiar: In the week following Abbott’s announcement, Texas raised $459,000 from private donors.

And if nothing comes of any of it, well, it’s not in Fisher’s nature to dwell on the negative. “Worst-case scenario,” he says, “I protected 3 miles of the southern border.”

Read next: How Mexico Forgot Its Covid Crisis

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.