Tom Barrack Got Trump Right, Then Things Went Wrong

For all of the loyalty, largesse Barrack bestowed on Trump since campaign began, the Colony founder has gotten little in return.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For Fourth of July weekend 2015, Patrice de Colmont, the owner of Le Club 55 near St. Tropez, decorated his restaurant with U.S. and French flags. Among the wealthy Americans there nibbling crudités and sipping Domaines Ott was financier Tom Barrack, who’d brought employees from his investment firm, Colony Capital. Fellow titans stopped by his table to say hello, including Blackstone Group LP co-founder Stephen Schwarzman, former Citigroup Inc. Chairman Sandy Weill, and hedge fund manager Dan Loeb.

Barrack had invited his deputies to the French Riviera to lay the groundwork for the Los Angeles-based firm’s newest fund. Building on a history of dealmaking that included Fairmont Hotels; the Miramax film studio, co-founded by Harvey Weinstein; and Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch, Barrack aimed to raise $2.5 billion to buy distressed European real estate assets and generate returns greater than 15 percent, a confidential investor pitch obtained by Bloomberg Businessweek shows. The conversations that weekend bubbled with optimism.

A few weeks earlier, Donald Trump, one of Barrack’s oldest friends, had announced he was running for president. The two real estate investors met in the mid-1980s, and Barrack entertained the crowd with war stories of deals they’d done together. While the campaign was the butt of many jokes at Le Club 55, according to two people who were there, Barrack startled guests with a different take. He said he thought Trump’s brash, authentic style would take him to the White House—and that he’d make a better president than candidate. Even employees who’d spent decades helping their boss place counterintuitive bets called the prediction crazy.

For Barrack, the tanned, bald, charismatic son of a Lebanese-American grocer from California, Trump’s candidacy became an obsession. In the months that followed, he would devote himself to Trump’s campaign, all but disappearing from the company he’d founded in 1991 and built into one of the world’s highest-profile real estate investment firms. While Barrack’s fundraising and TV appearances have been well-documented, he also assisted in ways that haven’t been reported. According to people familiar with the matter, he allowed Colony’s New York office, kitty-corner from Trump Tower, to be used for sensitive transition-team meetings. As a favor to Paul Manafort, a longtime friend he’d helped install as head of Trump’s campaign, he hired a woman whose duties included scheduling his campaign appearances. And he suggested that an investor familiar with Colony donate to a super PAC led by an ally of Manafort’s.

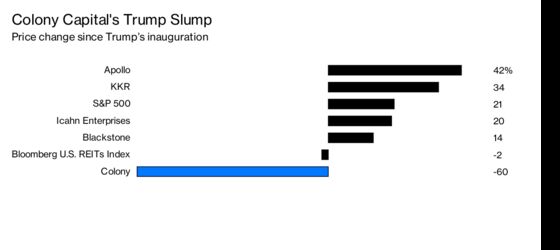

Helping a fading reality-TV star with no political experience capture the White House might have led to a role in the administration or made Colony a magnet for money from around the world. But mixing business and politics hasn’t worked out for Colony’s 71-year-old executive chairman. Instead, he damaged relations with the Qatari royal family, his best business partner in the Middle East, by helping orchestrate a relationship between the White House and the Saudis. Meanwhile, Colony hemorrhaged talent, raised only half the debt fund’s target, and entered into an ill-fated merger. Its shares have fallen about 60 percent since Trump’s inauguration, even as U.S. market indexes have risen more than 20 percent.

This story about Barrack’s misadventures in politics is based on interviews with more than a dozen current and former Colony employees, lobbyists, business partners, and campaign officials, most of whom requested anonymity to speak about private dealings. Barrack declined to be interviewed for this story, but his representatives dispute parts of this account. They say he remained engaged with the company, didn’t expect anything in return for making introductions to Middle East leaders, and continues to have excellent relations with rulers of Gulf countries despite increased feuding among some royal families.

“Barrack as chairman is responsible for creating a macro vision and expanding the global brand,” said Owen Blicksilver, a spokesman for Barrack, in a statement. “Politics around the world is an integral part of developing a vision.”

To the extent that he holds political beliefs, Barrack believes in Trump. He experiences politics largely on an emotional level, according to people who know him. A lifelong Republican, he’s nevertheless given money to California Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein, whose husband is a business partner. He briefly worked in the administration of President Ronald Reagan, whose Santa Barbara, Calif., ranch was near one of Barrack’s properties. Trump is just another rich friend, his rich friends say.

At first, Barrack’s campaign involvement was limited mainly to strategy calls with Trump. He’d long maintained a robust travel schedule, visiting company offices and attending investor meetings around the world while still finding time for polo and winemaking. Employees assumed he’d have no trouble balancing the campaign with everything else. Nevertheless, to his friends, it was clear he was becoming invested. “For anybody around him, you’d have to live inside a freezer not to realize he was getting more involved,” says Nacho Figueras, the Argentine model and professional polo star who frequently plays with Barrack.

By early 2016, Barrack’s agenda also included finalizing the sale of Colony’s stake in Miramax to the government of Qatar. The Gulf nation was already part owner of the Hollywood studio, having teamed up with Colony to buy it from Walt Disney Co. for $660 million in 2010. It was a typical deal for Barrack and Qatar. For years, when Colony bought an exotic asset—a French soccer team, a sprawling Sardinian resort—it was usually with Qatari backing. Those deals led to a friendship with Hamad bin Jassim bin Jaber Al Thani, better known as HBJ, who led Qatar from 2007 to 2013 and oversaw its wealth fund.

Barrack would do favors for the Qataris, including helping them wrest a controlling stake in London’s Claridge’s hotel from a pair of tenacious British billionaires; coordinating the construction of a 77,000-square-foot Bel Air mansion for HBJ, rumored to cost $100 million; and making political connections. With an estimated $335 billion under management, the Qatar Investment Authority is one of the shrewder funds in the Gulf, and its support for some of Barrack’s oddball purchases indicated to other investors that there was a method to his madness. After jointly holding assets for a few years, Qatari companies would buy out Colony for an impressive profit. The Miramax deal returned 350 percent, a person with knowledge of the transaction told Bloomberg when it closed in March 2016.

Things weren’t going as well in other corners of the Colony empire—by then shares of the company had fallen a third from a year earlier. The Trump campaign was a bright spot. On the last day of February, Barrack went public with his support for Trump, the first prominent Wall Street moneyman to do so, praising the candidate for his “mastery of financial, political, and economic intellectual complexity combined with his charm and emotional intelligence.” The next day was Super Tuesday, with primaries in 11 states. Trump won seven, cementing his status not just as one to take seriously, but as the one to beat.

How Trump’s and Barrack’s business histories yielded a friendship is something of a mystery. Their relationship began with Barrack helping to sell Trump two assets the latter couldn’t afford. The first was Alexander’s, a struggling department-store chain. In 1986, Barrack’s boss, Texas investor Robert Bass, sold Trump a 20 percent stake in the company, which Trump pledged as collateral for a bank loan and later had to forfeit to pay off the debt.

The following year, the Plaza Hotel was on the market. Barrack led negotiations for Bass and won the prize—then resold it to Trump, who coveted the landmark visible from his New York office. After months of bargaining, Barrack got Trump to pay about $400 million for the hotel, yielding Bass an estimated profit of more than $50 million in less than a year. Interest payments on the money Trump borrowed to finance the deal eclipsed the Plaza’s revenue, and by 1992 the hotel was forced into bankruptcy.

The two continued flirting with other investments. Colony considered refinancing a loan for Trump’s Manhattan West Side rail yards project but couldn’t make the numbers work. Barrack weighed buying a controlling stake in Trump’s casinos but acquired a competing Atlantic City venue instead, then hired a former Trump executive to run it. In 2012, when Trump won approval to convert Washington’s Old Post Office building into a hotel, Colony was initially named as the financier, until Deutsche Bank AG stepped in.

Still, the two remained friendly. Both have been married three times and have talked each other through divorces. They’ve been kind to each other in the business press, a venue of special importance to Trump.

The Plaza deal made Barrack’s career, launching him into the upper echelons of finance. But years later, when Barrack told the story of the transaction at the Republican National Convention in July 2016, he gave it a more self-deprecating cast. Glossing over the candidate’s financing difficulties and bankruptcies, he said Trump had “played me like a Steinway piano.”

A few months before the convention, with Trump’s campaign still hurtling toward the nomination and Barrack talking up the candidate on cable news, Saudi Arabia’s then-Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, better known as MBS, announced a bold plan to diversify the country’s assets in preparation for a post-oil world. State-owned Saudi Arabian Oil Co. would sell shares to the public and use the projected $2 trillion in proceeds to build up its sovereign wealth fund, he said in April 2016.

To find, buy, and manage the assets the country would be acquiring with the proceeds, it would need an army of financiers. Barrack, who’d played the same role for the Qataris, was one of many who wanted in, according to three people familiar with his thinking. As a young lawyer working for Richard Nixon’s personal attorney in the early 1970s, Barrack had been sent to Saudi Arabia to do work on behalf of engineering and construction company Fluor Corp., which in turn led to a friendship with a couple of Saudi princes. But the Saudi royal family is sprawling and fractious, and Barrack hadn’t done deals with the country’s sovereign fund. His principal connection was to Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, his partner in taking the Fairmont Raffles hotel chain private in 2006. But Alwaleed wasn’t close to MBS, and with the latter consolidating power in the kingdom, he’d be of little help to Barrack.

He eventually found his opportunity in Yousef Al Otaiba, ambassador to the U.S. from the United Arab Emirates and another longtime friend of Barrack’s. As the campaign heated up, Otaiba reached out to complain about Trump’s threat to ban Muslim immigrants around the same time as MBS’s announcement. In the byzantine world of Gulf royalty, Otaiba is a good friend to have. He’s aligned with Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the crown prince of Abu Dhabi, the largest by area of the seven emirates that make up the U.A.E. The Abu Dhabi crown prince supported MBS’s rise and had counseled him that a closer relationship with the U.S. was possible through improved ties with Israel.

“Confusion about your friend Donald Trump is VERY high,” Otaiba wrote Barrack in one of several emails obtained by the New York Times. Barrack advised Otaiba not to pay much attention to rhetoric, mentioned Trump’s real estate projects in Dubai, and arranged a meeting with the president’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, the published emails show. “Obviously I would like the meeting to be arranged by you and me rather than Blackstone,” he wrote in a separate email. (Barrack’s experience in the Middle East was a valuable resource to the Trump campaign and later the administration, said Blicksilver, Barrack’s spokesman. “The introduction to the leaders of the Arab world was not for political reasons but rather to form thoughtful points of view on the issues which had plagued the region for decades,” he added.)

Kushner was receptive to an alliance among Gulf countries, the U.S., and Israel, which he saw as a way to pressure Palestinians into accepting a peace deal. Barrack soon began talking up the Saudi line in public. “The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia and Israel—in my opinion—will align as allies very quickly here, and the world could change for the better,” he told Bloomberg TV in May 2016. Barrack went even further toward aligning himself with Saudi Arabia later that year, calling the kingdom “our longest and strongest ally” and “reliable defenders of the West’s diverse interests in the region.”

At home in the Colony offices, the situation was considerably less auspicious. The company was in the middle of a merger with New York-based NorthStar, whose chief executive officer, David Hamamoto, shared Barrack’s laid-back demeanor.

NorthStar was a mess. It had almost quadrupled the assets it had under management in two years by buying real estate portfolios with little regard for quality, funded with floating-rate debt. When rates started rising in late 2015, NorthStar’s interest payments did, too. That wouldn’t have been a problem were it not for how NorthStar was structured. The firm was an externally managed trust that was required to pay a nonnegotiable annual management fee of $186 million to another publicly traded company, also run by Hamamoto, no matter how it performed. Much of that went to the executive, resulting in a $75 million payout in 2014 that made Hamamoto one of America’s best-paid business leaders. To cover its interest payments, NorthStar had to weigh selling assets, which would threaten its ability to generate enough profit to pay the fees. Shares were plunging, and ratings companies threatened to reduce both NorthStar firms to junk status.

Barrack first discussed the idea of combining the companies with Hamamoto at New York’s Ritz-Carlton in January 2016, seeing a classic distressed-debt scenario. Colony executives talked about becoming the next Blackstone. Hamamoto, who didn’t respond to calls and emails seeking comment, saw something else, former employees say: an exit strategy.

Once the outlines of the deal were agreed on in mid-2016, the companies began to merge their operations. NorthStar employees, not all of whom were enamored with Trump, were struck by Barrack’s absences—and by the regularity with which they were asked to keep up with his political pronouncements. It was standard practice at Colony for employees to receive an email anytime he was going on television, followed by a link to the video of the appearance. Now those clips featured Barrack talking up Trump. Several complaints to human resources yielded no changes, former employees say.

With Barrack’s attention elsewhere, negotiations fell largely to his deputy, Colony CEO Richard Saltzman. The companies were hopelessly complex, with multiple business lines and subsidiaries. One of NorthStar’s main investment areas was health-care properties, where Colony had little expertise. Valuing the companies proved a challenge, even though both firms routinely made just these kinds of assessments. In the end, Saltzman and Hamamoto agreed to the bankers’ equivalent of throwing their hands up in the air: a merger of equals that assumed the companies’ stock prices accurately reflected the value of their underlying assets.

As negotiations entered their final stages, the Trump campaign was reaching its zenith. In at least one instance, according to a person familiar with the encounter, when an investor asked how best to back Trump, Barrack suggested the Rebuilding America Now super PAC, headed by a family friend of Manafort’s, Laurance Gay. (There was nothing improper in the suggestion. But the group later drew scrutiny for continuing to pay Gay $35,000 a month long after the election.) And in addition to hiring a woman at Manafort’s request, he later retained longtime Manafort associate and campaign deputy Rick Gates as a consultant to the firm. (Gates was fired after being indicted for lying to officials earlier this year. He later pleaded guilty.)

The deal closed in January 2017. A few months later a wooden crate showed up on the desk of an assistant to Hamamoto containing a book of leather swatches for use in custom yachts. Some employees took it as a sign that he was planning to jump ship—and that they should as well. By November, Hamamoto had submitted his resignation. Other NorthStar executives sold shares and left.

At the time of the merger, the combined company had a market value of about $8 billion. Today, investors value it at less than $3 billion. Saltzman has blamed the decline on “more challenging industry conditions” and a failure to raise as much capital as hoped.

Blicksilver, Barrack’s spokesman, said that while results have been disappointing so far, “there is no reason to believe this was attributable to any missteps on Barrack’s part, nor that it will not ultimately be a successful combination.”

Trump’s inauguration marked the peak of Barrack’s influence. The president-elect named him chairman of the inaugural committee, and he raised a record $106.7 million—important to a man who likes to claim records. On the day Trump took the oath of office, Barrack was seated behind Trump’s brother Robert and in front of Sheldon Adelson, the Republican Party’s most generous donor. Sporting a blue scarf and matching tie, Barrack smiled broadly and snapped photos.

Even as he celebrated, however, some within Colony worried. Management reminded employees that the firm had achieved new prominence thanks to the political activities of its founder, but many found that, to the contrary, its association with the president was producing headwinds. Fundraising in Europe, where Trump was unpopular, had become more difficult, and a pickup in Israeli interest wasn’t enough to close the gap. The debt fund Barrack had been so optimistic about stalled out at $1.3 billion, about half of the original goal. Blicksilver said it was a strategic decision to stop at that level.

Barrack’s diplomatic efforts were backfiring, too. Trump made Saudi Arabia the first stop on his first overseas trip in May 2017, partly as a result of Barrack’s lobbying. But a month later, just as MBS was being named crown prince, he and other Gulf leaders announced a blockade of Qatar, which they said was a financial backer of terror groups. (Qatar has denied this allegation.) Barrack was blindsided, one friend says. Trump’s tweet in support of the maneuver was a blow to Barrack’s credibility with his Qatari investors.

After the blockade began, Barrack reached out to then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who’d done business in Qatar as CEO of Exxon Mobil Corp., to help contain the fallout. But Kushner, who’d built a relationship with MBS and backed the blockade, had more influence with Trump, according to three people familiar with the matter. A spokesman for Kushner denies that he backed the blockade. In November, MBS detained Alwaleed, Barrack’s onetime Saudi investing partner, in the Riyadh Ritz-Carlton for three months in a crackdown targeting political rivals.

Former employees who worked with Barrack in the Middle East say he miscalculated. Being a Western dealmaker in Saudi Arabia was once a rare thing. Now the kingdom has relationships across Wall Street—including with Schwarzman’s Blackstone, with which it committed to invest $20 billion in 2017. Gulf royals, the former employees point out, tend not to like dealing with middlemen, which is what Barrack became when he helped secure access to the Trump administration. (Barrack never insisted on “being kept in the loop, being the middleman,” Blicksilver said.) In Kushner, MBS found his own princeling in the White House.

While the Qataris haven’t said a negative word about Barrack in public, and their U.S.-based representatives say they won’t, the royal family has looked to other administration officials for support and hired opposition researchers who are looking into Barrack’s dealings with Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E., according to three people familiar with the matter. Barrack still speaks with HBJ on a regular basis, Barrack’s friends say, and Blicksilver said his relationship with the Qatari royal family remains unchanged.

Barrack helped arrange an April 2018 meeting between Trump and Qatar’s new emir, 38-year-old Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, to whom Barrack had sold the Paris Saint-Germain soccer club in 2012. For Qatar, it represented a welcome, if belated, softening of the president’s stance. A month later, Barrack flew to Doha to meet with Tamim and talk investments, according to one person familiar with the meeting. No deals have been announced. On the other side of the blockade, Abu Dhabi bought a $70 million stake in a Los Angeles office tower partly owned by Colony, and the firm teamed up with the Saudi wealth fund to buy assets from France’s Accor SA. But Colony had owned a stake in Accor for years, so it hardly counts as new business.

As for Saudi Arabia, there may not be many more deals on offer. In August the kingdom postponed the public offering for Aramco, raising questions about how much investment will be coming from the country. MBS has become a toxic figure, tarnished by the October death of Saudi journalist and royal family critic Jamal Khashoggi inside the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul. Saudi Arabia has denied MBS’s involvement; nevertheless, executives including Schwarzman and JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s Jamie Dimon, as well as the CEOs of Uber, Viacom, and HP, pulled out of this year’s Future Investment Initiative conference, held the last week of October. Barrack, who attended the first Future Investment Initiative conference in 2017, backed out a few days before the gathering. He made his move after Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, with whom he’d been scheduled to appear on a panel, said he wouldn’t attend.

For all of the loyalty and largesse Barrack bestowed on Trump since the campaign began, the Colony founder has gotten little in return. Friends say he expressed interest in being named a presidential envoy to the Middle East, which would have given him a broad mandate to shape policy. Instead, he was handed the inaugural committee—a job he likened to being a wedding planner, according to two people who say they heard the remark.

Barrack’s ties to the campaign may come back to haunt him. Special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation inched closer to Barrack’s orbit with Manafort’s and Gates’s guilty pleas. Sam Patten, another Manafort associate, admitted to helping a Ukrainian oligarch disguise a $50,000 contribution to the inaugural committee in exchange for tickets. Three people close to Barrack say the committee didn’t have the tools to vet donors and that Barrack had no way of knowing the provenance of the funds. Barrack, who submitted to an interview by Mueller’s staff, “did so voluntarily, without a proffer or other agreement,” according to Blicksilver. Barrack hasn’t been accused of wrongdoing.

While Barrack’s be-nice-to-all style might be out of vogue in the era of Trump and MBS, friends say not to count him out. Figueras, the polo player, sees no sign that Colony’s reversal of fortune is weighing on him. “He never complains about anything,” Figueras says, adding that Barrack has told him he’ll be spending more time in South America. Colony is negotiating a deal to obtain the Latin American business of the Abraaj Group, a failing Dubai-based investment firm. Barrack has also raised $4 billion for a new Colony fund to invest in digital infrastructure such as cell towers and data centers.

Late last year, Barrack started spending more time in Colony’s offices and fewer hours on TV. He’s looking for opportunities to sell assets while boosting the fund management business. His relationships with sovereign wealth funds will be key.

“I am 100 percent focused,” Barrack told investors in March. “I am still one of the largest personal shareholders in this company, it’s the majority of my personal net worth, it’s the dominant factor in my and my family’s pride, reputation, and future, and I don’t intend to leave it tainted or unattended.” —With Shannon Pettypiece, Heather Perlberg, and Mohammed Aly Sergie

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Friedman at rfriedman5@bloomberg.net, Jillian GoodmanJeremy Keehn

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.