To Fix Its Housing Crunch, One U.S. City Takes Aim at the Single-Family Home

To Fix Its Housing Crunch, One U.S. City Takes Aim at the Single-Family Home

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The crowd at the Bauhaus Brew Labs was thick with flannel and knit beanies, with the odd “Beto for President” T-shirt thrown in. But the handful of patrons gathered by the glass garage doors of the cavernous Minneapolis taproom in March weren’t regulars. They’d turned out for the kickoff of a website called vox.MN. Their nametags said things like “I [heart] my neighborhood.” Another had a circle with “2040” inside and a line running through it, like a no-smoking sign.

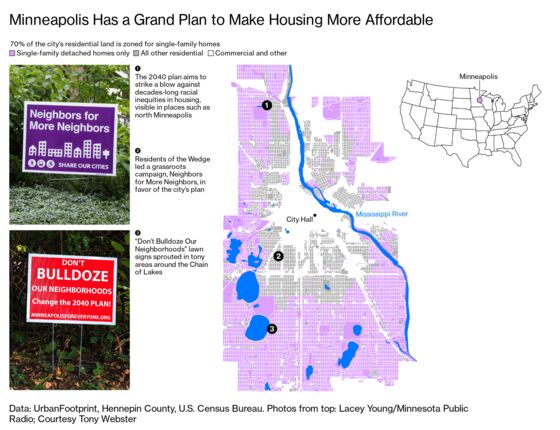

That was a reference to Minneapolis 2040, the sweeping new urban plan local officials approved in December. Spelled out in a more than 1,000-page document, it makes this city of 428,000 one of the first and largest in the U.S. to end single-family zoning, which applies to 70% of Minneapolis’s residential land. Developers will soon be able to build duplexes and triplexes without going through the time and expense of applying for a variance or confronting the kind of neighborhood opposition that often stymies such projects.

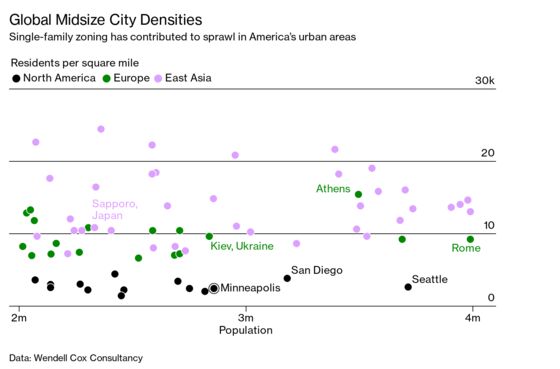

The move, which made national headlines, was widely celebrated by urbanists, who’ve long argued for more density. Restricting large swaths of U.S. cities to single-family residences limits the supply of housing, they argue, driving up prices, contributing to sprawl, and reinforcing decades of racial inequity. “Minneapolis 2040: The most wonderful plan of the year,” was the take of the Brookings Institution just before Christmas.

The praise has been echoed by, among others, U.S. Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson and the New York Times editorial board, which said the plan “deserves wide emulation.” Already, Oregon has followed suit with a statewide measure to do away with single-family zones in its cities, and policymakers from California to North Carolina are looking at the option, too. Democratic presidential candidates such as Cory Booker, Julián Castro, Amy Klobuchar, and Elizabeth Warren have offered related proposals.

Yet for all the fanfare, some residents in Minneapolis are seething over what happened. In the runup to the vote, they clashed with a well-organized and diverse group of proponents, flooding the city with comments. Red lawn signs warned ominously that neighborhoods of single-family homes would get bulldozed to make way for apartment buildings.

The nametag folks at the Bauhaus Brew Labs were certain the effort would end poorly. Mary Pattock, who served as communications director for the city’s first black mayor in the 1990s, said she and other white homeowners who campaigned against the zoning changes were made to look racially insensitive. “It’s kind of like Trump,” she said, clearly as an insult. “He doesn’t really say, ‘I hate black people,’ but he’s giving out those messages. That’s the way this plan was set up. It was set up to polarize on the basis of race.”

The 2040 plan also fomented divisions between young and old. “A lot of millennials feel like they’re taking it in the shorts” because high levels of college debt and rising real estate prices have put homeownership out of their reach, said another anti-2040 activist, retired council member Lisa McDonald. “My husband and I were pretty poor when we started out,” she added. “We basically scrabbled, renovated houses ourselves, until we were able to live where we live now”—a $1.6 million home on one of the city’s large, picturesque lakes. “Should we be penalized for that?”

At some point, McDonald said, younger people will have kids and want to own a single-family home just as her generation did. “Let’s try to think about that, and not be, basically, hanging our future on just renters,” she says.

Carol Becker, standing nearby, chimed in: “They’re going to spawn, man!”

Breeding habits aside, there are economic issues at stake, along with the city’s goals of making housing more affordable and equitable. Academics have started to quantify the costs that local restrictions on land use can inflict nationwide. In a recent paper, Chang-Tai Hsieh, of the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, and Enrico Moretti, at the University of California at Berkeley, argued that barriers to building more homes in New York, San Francisco, and San Jose lowered U.S. economic growth by 36% from 1964 to 2009. Impediments to housing supply in these highly productive places effectively kept Americans from making an additional $3,685 per person per year by 2009, they found.

Minneapolis isn’t Silicon Valley, and no one is suggesting that allowing more development in a midsize Midwestern town will turbocharge U.S. growth. But the city’s drive to boost density could have benefits beyond its borders and set an example for the rest of the country, Moretti says. “It’s not just good for Minneapolis, it’s good for the rest of the U.S., as well.”

About a dozen city staff worked on the 2040 plan for roughly two and a half years. But its biggest political champion was Minneapolis Council President Lisa Bender, a 41-year-old former city planner and cycling advocate. She’d moved back home to the Twin Cities with her husband in 2009 after stints in New York and the Bay Area, lured by the great parks, top-notch public schools, and what then was reasonably priced housing. Even so, Bender says, she could see that Minneapolis faced a “looming affordability crisis.”

In 2013 she decided to contest her local council member’s seat. A Facebook post from the time shows her, nine months pregnant, canvassing on a bicycle. “I ran for election explicitly saying we need more housing,” says Bender, who gave birth to her second child a month before winning office.

Minneapolis’s population was already growing rapidly, jumping by about 46,000 people, or 12%, from 2010 to 2018, as younger people settled in the city instead of the suburbs. Rents rose briskly, and apartment vacancy rates plunged to some of the lowest levels of any major U.S. metro area. The inventory of homes on the market dwindled, spurring bidding wars. “The price of coffee hasn’t changed in five years, but housing costs 40% more,” says Aaron Eisenberg, a real estate agent who often works with first-time buyers.

Millennials struggling to find houses in their price range were just the tip of a much deeper problem. Minneapolis, like many U.S. cities, has a history of segregation reinforced by federal, state, and local housing laws. Almost 60% of white residents own a home in the city, but only about 20% of blacks do, one of the largest differentials in the nation and a big reason for the yawning racial wealth gap. In the 20th century, “you had these intentionally segregationist and racist policies” that barred blacks from living in certain parts of town, says Mayor Jacob Frey, 38, who backed the plan. When those laws became illegal, the city “started doing it in other ways, through our zoning code,” he adds. “That’s what we’re pushing back on.”

In her freshman term, Bender championed a law that allowed homeowners to build backyard cottages as a way to encourage more density in single-family neighborhoods. She also quietly began laying the groundwork for more ambitious reform. Every 10 years, local governments in and around the Twin Cities are required to submit a long-range plan to a regional council. Minneapolis had done a good job of charting a vision for its transit system, Bender says. But it had never focused on what it would mean to make access to housing more inclusive. The city likes to think of itself as progressive, but Bender knew changing zoning would be controversial. People “start to have a lot of emotion around what’s my community going to look like, how do I fit in here” when you start talking about what could get built on their corner, she says.

Another challenge: Work on the plan would straddle an election year, putting into question whether there’d be political backing for some of the more controversial ideas. As Bender campaigned for her own reelection, she also threw her support behind other pro-growth candidates committed to making housing more affordable and racially equitable.

One was Phillipe Cunningham, a black, transgender former mayoral aide who won a seat in 2017, beating a long-serving council president. Cunningham had witnessed the effects of the housing crunch in his own ward, a diverse, working-class area in north Minneapolis. Buyers who were getting priced out of other parts of town were increasingly moving into his neighborhood, driving up home values. Investors had targeted the area, too, snapping up single-family homes that could be turned into rentals. “I’m not OK with my constituents being displaced by people with higher incomes,” Cunningham says. “We need to build more places for people to live.”

By the time the new council was sworn in at the beginning of 2018, city staff were deep into their work on the 2040 plan. They held dozens of information sessions around the city, including on public transit. “We’d just get on the bus and talk to people,” recalls Heather Worthington, director of long-range planning.

The city released a draft in the spring. The backlash came quickly. One of the ringleaders was McDonald, the retired council member, who’d cultivated a brash, tough-talking image during her years in office. (A local weekly newspaper once ran an image of her astride a motorcycle, with the headline “Hell on Wheels.”) Another was Becker, a member of the city’s Board of Estimate and Taxation and a longtime fixture of local Democratic politics. The group they fronted, Minneapolis for Everyone, made red “Don’t Bulldoze Our Neighborhoods” lawn signs that started cropping up around town, mostly in the whiter, wealthier neighborhoods in the southwestern quadrant of the city.

Advocates, who’d anticipated the blowback, formed a rival group called Neighbors for More Neighbors. The name was a wry take on how Nimbyism (“not in my backyard”) finds expression in slogans like, “Neighbors for This, Neighbors for That,” says John Edwards, a local blogger and the group’s co-founder. It turned out to be a positive message that resonated with a wide swath of Minneapolis, helping build grassroots support.

As the two sides battled into the fall, the public remained sharply divided. A review by the Star Tribune of a sample of the more than 18,000 comments collected by the city showed that critics outnumbered supporters 2-to-1. Worthington, whose staff reviewed all the feedback, said those in favor had an edge.

Meanwhile, Bender was working to win over her council colleagues. A revised version of the plan capped the number of units that could be built on lots zoned for single homes at three, instead of the fourplexes allowed in the draft. In December the council approved the document in a 12-to-1 vote. As media outlets across the country took note, Bender tweeted: “We have inspired a national conversation about racial exclusion in housing and how cities can move forward to do better.”

The reality on the ground is, of course, more nuanced than the dueling lawn signs make out. “From the front, we designed this to look like a single-family home,” says Bruce Brunner, standing outside his latest project in south Minneapolis. The framing is done, revealing a roofline that fits with the stately, century-old homes that line the street. Instead of housing one family, though, each floor of the three-story building will be a separate 1,247-square-foot, three-bedroom, two-bathroom apartment.

Brunner, a former Target Corp. executive-turned-builder, had been planning to put just a duplex on the site, but the neighborhood association encouraged him to try for three units instead. There was just one hitch: The city’s zoning code wouldn’t permit it. So Brunner ended up taking his case to the planning commission for a variance. “One of the funny things is that the only person who opposed it lives in that fourplex,” he says, motioning to a building down the block that dates from an earlier era when they were allowed. “They said, ‘If you let them build the triplex, it’s going to ruin the neighborhood.’ ” He got the approvals anyway, but the process dragged out.

On principle, Brunner is a fan of the 2040 plan, which will clear away some of that red tape. He lives in a nearby duplex and supports the city council’s social goals. Still, he’s skeptical that upzoning single-family neighborhoods will translate into a massive business opportunity. Small projects like his are too idiosyncratic for most big developers to bother with. Even for smaller players, triplexes often don’t pencil out; construction and land costs are too high compared with the rents a landlord can expect to charge. For most lots in the city, Brunner says, “the equation doesn’t work.”

Adding a bunch of duplexes and triplexes is also a pretty inefficient way to solve the housing shortage. What’s needed are big and midsize apartment buildings. Minneapolis officials know this, which is why the 2040 plan allows for larger developments around transit hubs and select other areas. To ensure the new rentals are affordable, the council adopted a temporary measure that requires certain new buildings to earmark at least a tenth of their units for residents making as much as 60% of the area median income, charging about $1,350 a month for a two-bedroom. Lawmakers also intend to pass a permanent ordinance to make sure the city ends up with a mixture of housing, not just luxury apartments.

The real estate industry has its doubts. The council seems to think the affordable units will “just come out of developer’s hide,” says Steve Cramer, president of the MPLS Downtown Council, who brought together for-profit and nonprofit developers to weigh in on the policy. Last year the group estimated the industry needed to sink more than $3 billion into housing just to make up for a decade of underbuilding in Minneapolis and an additional $1.3 billion every year to keep up with population growth. It’s unlikely developers will appear with that kind of money, given the current policy. “That’s the fundamental fallacy of this,” Cramer says. “These projects just won’t get financing.”

Developers are raising some valid concerns, says Andrea Brennan, the city’s director of housing policy and development. Still, Minneapolis wouldn’t have gone through “all this trouble to create this very permissible development environment if we didn’t want development,” she says. “The question before us really is, who benefits from growth?”

On some level, the most striking thing about the 2040 plan is that it passed at all. It takes political courage to approve a policy so farsighted many of the officials who voted for it will be out of office by the time anyone knows if it worked. Bender says the changes “are incremental enough and moderate enough that people won’t see the huge things that they’re really afraid of.”

Yet that also suggests that people who expect the plan to quickly make housing more affordable and equitable in Minneapolis may be disappointed. The problem, as Bender and others point out, has been decades in the making and will take years to fix. And much of what’s in the plan is far from finished policy. Even the change to allow triplexes on single-family lots still has to be enshrined in the zoning code, a step the city plans to take when it receives a final signoff from the regional council, which is expected in September.

These are just local fixes to a problem that, on many levels, only the federal government has the resources to solve. The U.S. has cut housing assistance by two-thirds since the late 1970s, putting pressure on cities and states to help low earners, whose wages haven’t kept up with rising housing costs. Last year, Mayor Frey budgeted a record $40 million for affordable housing, but much more will be needed. In the meantime, the counterrevolution is in motion. A lawsuit filed to halt the plan on environmental grounds was dismissed in April, but the plaintiffs are appealing. And there’s a nascent effort to revamp how the city elects council members in a way that critics say could give more power to the whiter, wealthier parts of the city. Even if that doesn’t come to pass, the 2040 plan is almost certain to be an issue in the next council elections in 2021.

Minneapolis was able to do something bold precisely because housing costs haven’t gotten too out of control, says David Schleicher, a professor at Yale Law School who studies land use and urban development. In California, he says, the economic interests of homeowners are so entrenched that the state is stuck despite well-organized efforts at reform. The most recent attempt would have applied a plan similar to Minneapolis 2040 to the entire state. It was tabled in May after pushback from suburban legislators. “Once you’ve hit the point where you see these fast-accelerating property values,” Schleicher says, “it gets harder and harder to do this.”

Homeowners still vote in strikingly higher numbers than renters in the U.S. (Nationwide, the ratio in 2018 was about 3-to-1.) Foes of the 2040 plan who showed up at the vox.MN event are counting on returning people with their views to office. But, as the city’s recent past shows, plenty of homeowners will go along with something that’s not in their economic interest if they see change in a positive light.

Take David Brauer. He moved to Minneapolis in 1979 and covered the city as a journalist. For years, he says, local leaders tried to get any development they could going. Big corporations, such as General Mills Inc., had decamped for the suburbs, while a spate of homicides in the 1990s earned the city the nickname “Murderapolis.” But steadily things came back. “We were lifted by the trends you see nationally—younger people bored with the suburbs,” he says.

Now that he’s retired, Brauer and his wife are thinking about putting their single-family in south Minneapolis up for sale. “We want to stay in the neighborhood,” he says, but there aren’t many choices for those looking to downsize. That’s why he’s a supporter of the 2040 plan. If it creates the sort of housing options in the years ahead that boomers like him want, they’ll move, making way for millennials—and their spawn.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net, Max Chafkin

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.