Salesforce’s Success Rides on One Man’s Gut

This Software Giant Runs on One Man’s Gut

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Marc Benioff wanted everyone to know the statue was “a very, very big deal.” The software billionaire, a lover of all things Hawaiian, spent $7.5 million at auction in late 2017 for a centuries-old carving of the war god Ku and made a show of donating it to a museum in Honolulu last spring. Hawaii has shaped Benioff’s spiritual beliefs and fostered his boldface-name friendships, and he framed the donation as a way of giving back to the community, saying he didn’t want to hoard the statue’s spiritual power. It’s possible he needn’t have worried: A couple months ago, some art experts began arguing that based on the uncertainty of its provenance, the Ku figure is likely a tiki-bar-caliber tchotchke worth less than $5,000. A spokeswoman declined to comment on the statue’s value.

The co-chief executive officer of Salesforce.com Inc., which makes America’s dominant sales-tracking software, puts a lot of faith in his gut. Interviews with Benioff and 18 current and former Salesforce employees and other friends and associates of the CEO make clear he operates more on spur-of-the-moment instincts than on a grand strategy. On the whole, that’s worked out incredibly well. Most companies taking in $13 billion a year don’t grow the way Salesforce does. Now entering its third decade, with a market capitalization of more than $120 billion, its revenue is still increasing 26% a year.

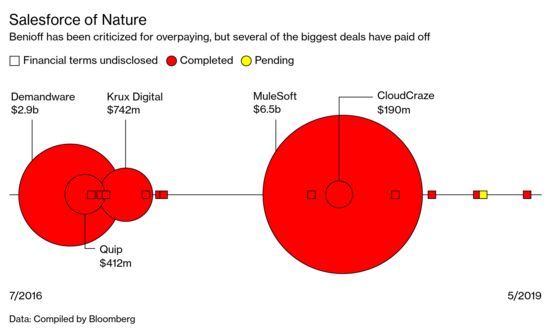

The secret is deals. Benioff has kept up the momentum by acquiring more than 60 companies in 20 years, including a string of fast-growing businesses in marketing, e-commerce, and data integration. Sometimes he’ll buy a company during a meeting that had nothing to do with acquisition talks. And the CEO readily acknowledges that he can’t always explain how he arrived at those decisions. “It’s hard, because I’m somebody who can see things that other people can’t see,” he says. “It’s frustrating when I can’t communicate what I’m feeling. This is one of my challenges.”

Benioff says he doesn’t move forward with acquisitions without aye votes from three or four lieutenants. But Salesforce also frequently pays above top dollar, and this black box of big decisions can also lead to some expensive misfires, soured relationships with peers, and question marks like the war god statue. Once, when a customer asked when to expect access to Salesforce’s software, Benioff couldn’t help, he said, because he “lived in the future,” according to Alex Dayon, the company’s chief strategy officer.

That’s troubling when it comes to bet-the-company moments, says Pat Walravens, an analyst at JMP Securities who’s focused on Salesforce for more than 15 years. “Benioff and Salesforce were willing to spend a lot more money than we would have imagined” in bids for LinkedIn and Twitter Inc., Walravens says, offering to give up as much as half the company. “For me personally, Twitter was scary, because I didn’t understand it.”

Believers say that’s all just part of the process. “To the uninitiated, he’s like a Zen Buddhist,” says Tien Tzuo, one of Salesforce’s earliest employees and now the CEO of Zuora Inc., a billing company for subscription services. Asked about his missteps, Benioff points to Salesforce’s many triumphant acquisitions. “There’s not a lot of other software companies who have this kind of track record,” he says, and that’s undeniable. Still, the past few years are also littered with major deals scuttled in part by Benioff’s interpersonal relationships, including what would have been the biggest deal of all: selling Salesforce to Microsoft Corp.

A few of his purchases (ExactTarget Inc., Demandware Inc.) have added significant dimensions when stitched into Salesforce’s primary cloud products. Some have been less ready for prime time. Partly out of regret that his deputies talked him out of a bidding war for the service that became Google Docs, the CEO spent $412 million in 2016 on Quip, a small competitor to Google’s G Suite. Quip lacked basic font and formatting options, couldn’t make PowerPoint-style slides, and slowed to a crawl when, soon after the deal, Salesforce executives tried to use it to discuss their annual goals with employees. At best, it was a hyperexpensive way to hire Quip’s co-founder and CEO, Bret Taylor, who was formerly the chief technology officer of Facebook Inc. Taylor is now Salesforce’s chief product officer. “Marc is more willing to reconceptualize what Salesforce is than other people,” he says.

Sometimes, Salesforce deals move too fast for its partners to keep up. A few years ago, Benioff offered to buy SteelBrick, which makes software to help businesses figure out the maximum they can charge customers for a given product, in the middle of a meeting about the two companies’ partnership opportunities. The news came as a shock to executives at SteelBrick and at Apttus Corp., a company Salesforce had already teamed up with in the same market. Apttus expected to be the one to get the buyout offer, according to people familiar with the matter. “If you want to be acquired by Salesforce, then the best thing is for you to be making our customers successful with your product,” Benioff says.

Within Silicon Valley, Benioff’s reputation as an emotional buyer has led startups to make some dramatic moves of their own to attract his attention, including hiring away Salesforce employees to make an introduction to Benioff or moving into Salesforce Tower, San Francisco’s tallest building, which opened last year. The CEO says such tricks don’t work on him, though he did agree in April to buy partner MapAnything Inc., whose CEO used to half-jokingly ask Salesforce executives during meetings when they planned to acquire the company.

The offers aren’t always so eagerly received. In 2016, Benioff gave up on an attempt to purchase Twitter after news of his interest tanked Salesforce’s share price. The same year, after he confided his interest in LinkedIn to his buddy John Thompson, the chairman of Microsoft and a neighbor in Hawaii, Microsoft—long interested in the company—bought it instead. LinkedIn’s founder and CEO ignored an offer from Benioff above Microsoft’s $26 billion purchase price, according to a filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. That deal left Benioff furious, according to one of the people, but Benioff says that’s in the past. “I’m quite spiritual when it comes to these things,” he says. “If it wasn’t meant to be, it must not have been.”

Microsoft, more than any other company, may have tested Benioff’s Zen. The two sales teams have competed for years in the dry field of customer-relationship management software, and while Benioff grew close with CEO Satya Nadella shortly after Nadella was appointed in 2014, that changed with the LinkedIn deal, according to people familiar with the matter.

Benioff’s frustrations were already building by then. When he was looking to sell Salesforce to the Windows maker in 2015, he wanted $70 billion for the company, while Microsoft’s offer topped out at $55 billion. Had the difference narrowed enough for Microsoft’s leaders to take up the question, another issue might have arisen: Benioff, who’d already cultivated a reputation as a pugnacious director in two tumultuous years at Cisco Systems Inc., wanted to join Microsoft’s board. He would sometimes videoconference into Cisco meetings from Hawaii wearing a tank top while exercising on an elliptical trainer, scandalizing the board’s corporate retirees, someone familiar with the matter says.

Outwardly, Benioff is calmer about those setbacks than that portrait suggests. “If there’s one thing I don’t like, it’s when I don’t get my way,” he says with a fair amount of cheer. As he searches for the next hit business to bolt on to Salesforce, he can’t afford to hold on to negative feelings, he says. Some things are much bigger than him and others much too small. Of course, some, like the Ku statue, could be either. —With Dina Bass and Ian King

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Dimitra Kessenides at dkessenides1@bloomberg.net, Jeff Muskus

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.