This Pro-Brexit Seaside Town Is Starting to Fret

This British Seaside Town Is Dreading Brexit

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On any given weekday in the British seaside town of Bournemouth, surfers can be found dragging in their boards from the sandy beach to get smoothies and beers. Retirees and office workers take midday strolls along a seaside path lined with busy seafood restaurants and ice cream stalls.

A visitor to this city of 193,000 on the southwest coast of England would have trouble discerning signs of a Brexit-induced slowdown. Bournemouth is home to two universities, a 4,000-person JPMorgan Chase & Co. back-office operation, and a larger-than-normal collection of white-collar service businesses, including law firms, digital startups, and health-care providers. Their combined presence lends the place an economic vibrancy that’s long been missing at other seaside resorts in the U.K. Nevertheless, interviews with local executives and government officials indicate that Britain’s decision to quit the European Union is taking a toll. They speak of delayed investments, labor shortages, and budget cuts that appear to threaten the area’s prosperity.

Duncan McWilliam says he chose to start his visual-effects studio in Bournemouth five years ago, because overhead costs are lower than in London and the lifestyle is more relaxed. Now, though, he plans to open an office in Barcelona instead of expanding in Britain. “We built the Barcelona plan in to give investors confidence that no matter what the government do, we’ve got a plan B,” says McWilliam, whose Outpost VFX has worked on the Jason Bourne and Jurassic Park film franchises. “That’s very labor-intensive, and highly speculative, and a real pain in the butt.”

The U.K. is scheduled to quit the EU in March 2019, and it’s still not clear if Prime Minister Theresa May will succeed in securing a deal with Brussels in time to avoid the country being ejected from the bloc with no new arrangements in place. Even if an agreement is reached on what trade ties should look like, the government’s approach has so far focused on trade in goods and not on services.

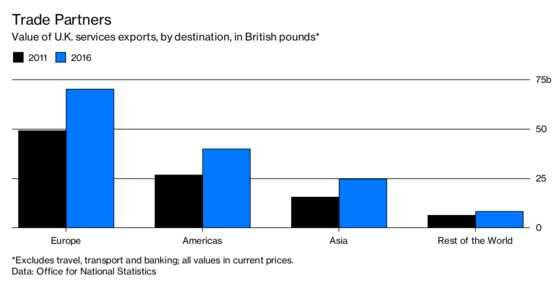

It’s a glaring omission, considering the U.K. is the second-biggest exporter of services in the world and its largest trading partner is the EU. Bournemouth’s services exports totaled £873 million ($1.1 billion) in 2015, according to the Centre for Cities, a London think tank. The sector accounts for almost 90 percent of employment in the area. “Because it’s such a service-based economy, the single market is really important for Bournemouth,” says Clare Moody, a member of the opposition Labour Party who represents the South West England region at the European Parliament in Brussels.

Membership in the 28-country bloc confers sizable benefits on U.K.-based companies: They enjoy access to a market of 500 million consumers, free flow of data, and “passporting” rights, which allow financial companies to market products and services in any EU country without having to set up a branch there. The union also allows for free movement of people, crucial to services companies that employ European staff in Britain or send workers on day trips to the Continent for such things as installing software or drafting contracts.

Peter Phillips, chief executive officer of Unicorn Training Group Ltd., a Bournemouth-based company of about 130 that develops corporate education programs on topics such as financial crime and data protection, says he’d consider opening an office on the Continent if U.K. companies lost their ability to passport. “A lot of people would then have to leave,” he says. “There’s a sense in the industry that we still have no idea what’s going to happen.”

JPMorgan’s staff in Bournemouth, where the U.S. financial company ranks as the biggest employer, are well aware of the risks. Just weeks before the June 23, 2016, referendum, CEO Jamie Dimon and then-Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne visited the office, which is located on a grassy campus just outside the town center, to warn that as many as a quarter of the bank’s 16,000 jobs in the U.K. could be lost if the country voted to leave the EU. (Dimon’s doomsday message appears to have fallen on deaf ears: The pro-Brexit vote in Bournemouth was 55 percent, about 3 percentage points higher than nationwide.)

Two years later, JPMorgan’s presence in Bournemouth hasn’t shrunk. It hasn’t expanded, either. The bank did announce plans last year to add thousands of back-office jobs in Europe. But they’ll be in Poland, where wages are lower.

A pre-referendum analysis by the U.K. Treasury presaged that a win by the “leave” camp would unleash a yearlong recession. While that forecast proved overly dire, there have been economic consequences. The U.K. was the only Group of Seven nation where growth slowed last year. Other predictions from economists, including those at the Bank of England, were on the mark: The pound weakened in the vote’s aftermath, driving inflation above the bank’s target of 2 percent and triggering the first interest-rate hikes since the financial crisis.

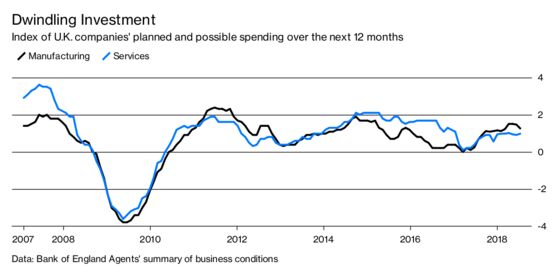

There are more red flags. Growth in business investment is running at 4 percent a year rather than the 10 percent-plus that would be normal at this stage of the economic cycle. Migration from the EU to the U.K. has plunged by more than half since the Brexit vote—and that’s without any formal change in the government’s policy. Add it all up, and you have what economists call a supply-side shock. In February the Bank of England said the U.K.’s potential growth rate, or the pace at which it can expand without generating excessive price pressures, has fallen to just 1.5 percent, compared with about 2.5 percent previously.

“It’s not just that you’re not growing, it’s that you’re shrinking relative to other countries,” says Moody, the EU parliamentarian. She’s right, in that the economic picture across much of the Continent has improved while the U.K.’s has worsened. “We are almost certainly in an opportunity cost situation now, with unknown lost investment that would have happened.”

The combination of factors that used to draw Europeans across the English Channel—a robust economy, a strong pound, and certainty over rights to live and work—has lost some of its potency. In Bournemouth, the tourism and health industries are struggling to recruit, having traditionally relied on migration from the EU to fill posts. Bournemouth University also had openings recently that, for the first time, had no applications from EU candidates, according to one professor. Brussels has said it won’t accept a divorce settlement that allows British businesses continued and unfettered access to the single market while permitting the U.K. to impose curbs on migration.

If there’s no agreement reached by the prime minister’s self-imposed deadline of March, British companies doing business on the Continent will immediately be subject to “host state rules.” That means they’ll get the same treatment as, say, China, when trading with or setting up a presence in one of the bloc’s nations. “The commercial equation that businesses have to take is, how much would it cost us to comply with six or seven different regulatory regimes, plus the uncertainty of what a trade deal is going to bring, plus I don’t know whether I can send my service providers from the U.K. to go in and put in the software in our customer offices in Germany,” says Paul Hardy, Brexit director at law firm DLA Piper in London.

The uncertainty is making it difficult for companies in Bournemouth to plan. Matt Desmier, a self-employed consultant who used to organize a “Silicon Beach” festival for digital startups in the area, canceled this year’s event after sponsors pulled funding. His own income has dropped by half since the referendum, because companies are much less willing to allocate money toward external expertise. “People are waiting,” he says. “They’re spending the bare minimum that they have to because they have no idea what’s going to happen next.”

Tobias Ellwood, a Conservative Party lawmaker representing Bournemouth East who’d pushed for the U.K. to stay in the EU, says the city can’t afford to stand on the sidelines while things get sorted out. During an interview at an area restaurant, where waiters wearing sunglasses circulate with plates of crabcakes and oysters, Ellwood says Bournemouth should do more to tout itself as an attractive location for British businesses that may be priced out of the capital. “It’s as easy to fly from London to Barcelona as it is to go from London to Bournemouth,” he says. “So we need to keep ourselves on the map, we need to make ourselves relevant.” —With Neil Callanan

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.