There Was Another Concert in 1969 That Changed Pop Music

There Was Another Concert in 1969 That Changed Pop Music

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The summer of ’69 permanently altered the landscape of popular music. A certain concert was so unprecedented, so unforgettable, that it would serve as a touchstone for an entire generation.

No, not Woodstock. Elvis. In Las Vegas.

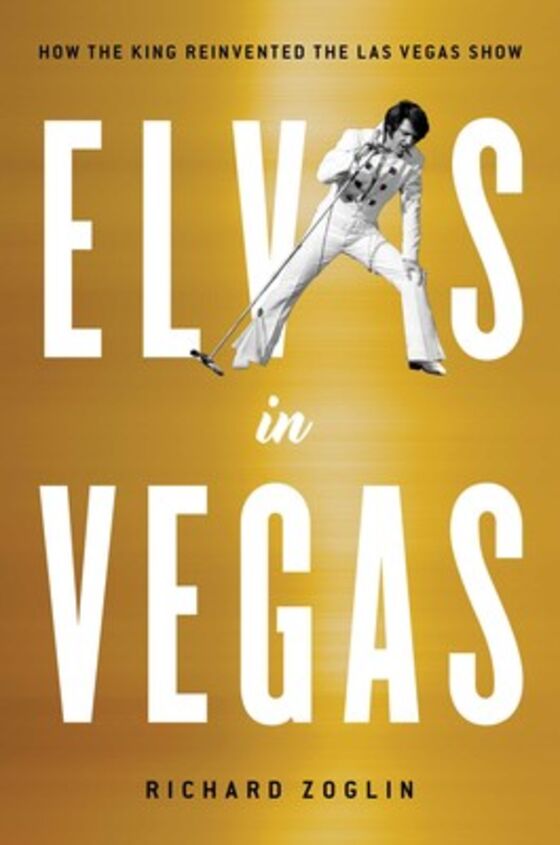

At least that’s what Time contributor Richard Zoglin argues in Elvis in Vegas: How the King Reinvented the Las Vegas Show (Simon & Schuster, $28). In the book, the author retraces the events that transformed Elvis into the sequin-jumpsuited hunka-hunka burning love we know today. Zoglin writes that the sheer spectacular-ness of the performance influenced the most successful acts to follow, whether Celine Dion or Blue Man Group, Cirque du Soleil or Lady Gaga.

Elvis was not cool in ’69. “You have to remember how the counterculture hated him,” rock critic Richard Goldstein is quoted as saying. “He was doing music we considered plastic.” Elvis had spent the ’60s woodenly starring in formulaic Hollywood musicals, but a televised “comeback special” in December 1968 suggested a still-relevant singer lurked inside.

Rock ’n’ roll was not cool in Vegas either. But Elvis had been infatuated with the place since his first performance there in April 1956, just as Heartbreak Hotel hit No. 1, and he returned often just for fun. For his first live performance in a decade, his manager, “Colonel” Tom Parker, made arrangements with the new International Hotel, Vegas’s largest, which had a 2,000-seat showroom. Elvis would be paid a then-record $125,000 a week—more than $850,000 today.

At the time, the Strip’s biggest acts were still Frank Sinatra, who earned $100,000 a week at Caesars Palace, and Dean Martin, at the same rate, at the Riviera. “Even as the ’60s revolution was challenging old taboos,” Zoglin writes, “Vegas was still conservative. Its mostly middle-aged Middle American audiences didn’t want to be provoked. They wanted reassuring entertainment.”

In retrospect it wasn’t that much of a gamble. By ’69, Sinatra’s power was ebbing, and Elvis was the change that Vegas had been waiting for. He did two shows each night for four weeks and played his ’50s hits, including Mystery Train, Don’t Be Cruel, and Blue Suede Shoes.

Even by Vegas standards, the show was over-the-top: almost 60 musicians onstage, including a full orchestra, two backup singing groups, and a rhythm band. Elvis wore a jumpsuit designed by Bill Belew to show off his beloved karate kicks. Vegas regular Tom Jones taught him the trick of wiping his face with a handkerchief, then throwing it into the crowd. People got seriously shook up. The show set an all-time record for attendance, drawing 101,500 people, and every performance sold out.

Peter Guralnick has already covered a lot of this ground in his landmark two-part biography, Last Train to Memphis and Careless Love, and Zoglin cherry-picks some of Guralnick’s choicest quotes. My favorite: “He loved Vegas for one reason above all: time was meaningless here, there were no obligations. It was a place where you could lose yourself, a place you could indulge your every fantasy.”

The real achievement of the book, then, is how Zoglin traces the evolution of Vegas itself, from its incorporation in 1905 as a stopover for railroad passengers heading west to the seismic changes in 1931, when gambling was legalized and construction on the Hoover Dam began, introducing an itinerant workforce looking to blow off steam.

Zoglin recounts the rise of the Flamingo in 1946, funded largely by mobster Bugsy Siegel; the competition between the Sahara and the Sands hotels, both built in 1952 when the city was already averaging almost 8 million tourists a year; and its corporate transformation after Howard Hughes and Kirk Kerkorian began erecting massive temples in the desert dust.

At the book’s core are the shows. Zoglin delves into the Rat Pack’s boozy “broads-and-dagos” routine that, for all the crude antics, were intimate affairs aimed at a sophisticated audience and high rollers. Elvis changed that calculus. His “bombastic stage shows came to symbolize the gaudiness, fakery, and middlebrow bad taste” that still cling to the city.

And as the excesses take their inevitable toll, this career resurrection proves to be a hollow one. Despite his well-chronicled drug abuse, Elvis still did 636 shows over seven years, every one a sellout—but with the diminishing returns of an addict.

As we know now, the house always wins. “I make the same [money] as other entertainers who work in Vegas,” Jack Benny once joked. “The only difference is that I take mine home.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Chris Rovzar at crovzar@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.