There’s a Diesel Cloud Hanging Over Angela Merkel

There’s a Diesel Cloud Hanging Over Angela Merkel

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- With her support of the Paris climate accord and decision to shutter Germany’s nuclear power plants, Angela Merkel has earned a reputation abroad as the “climate chancellor.” But throughout her 13 years in office, Merkel has had a blind spot when it comes to the auto industry—which employs more than 800,000 people in her country—embracing German carmakers and continuing to champion diesel even after Volkswagen AG admitted three years ago to cheating on emissions tests. Merkel has long been more “car chancellor” than climate chancellor, says Jürgen Trittin, a former Green Party environment minister, and today her auto policies are “crashing into pieces.”

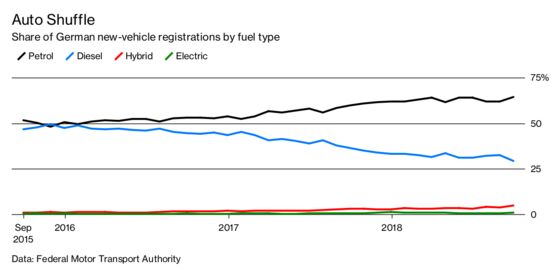

While recent elections indicate Merkel’s power is ebbing, her position is being complicated by a growing number of court rulings poised to ban diesel cars from city centers. For two decades, German auto manufacturers touted diesel as a green technology, mostly because it offers 20 percent to 25 percent better fuel efficiency than similar gasoline-powered cars, releasing less carbon dioxide. But that comes at the cost of nitrogen oxide emissions that have been linked to heart disease, strokes, and respiratory problems. Environmental groups have lodged dozens of anti-diesel lawsuits, and judges have ruled in favor of limiting the use of diesels in a half-dozen cities, including Berlin, Frankfurt, and Munich. “Merkel has totally misjudged the problem for a long time,” says Jürgen Resch, executive director of Deutsche Umwelthilfe, an environmental group that’s brought many of the lawsuits. “The government totally surrendered to the auto industry.”

Merkel acknowledges she must maintain a strong dialogue with the automakers, but she insists that she hasn’t gone easy on them. Industry executives, though, fear they may be losing the chancellor’s ear at a time they need it more than ever. The big German brands are stepping up spending to develop electric cars to meet stricter rules on emissions, and they’d been counting on diesel to meet CO₂ targets and fund the transition to battery-powered vehicles.

In early October, Merkel called on automakers to update older engines to be less polluting. Manufacturers say that would be hugely expensive—as much as €5,000 ($5,700) per car—and that it’s smarter to subsidize purchases of cleaner vehicles. They advocate a strategy like the “cash-for-clunkers” programs in Germany and the U.S. a decade ago, which offered an outsize trade-in value for older cars.

But Merkel is facing growing voter anger over potential restrictions, which could affect almost 10 million diesels. A mid-October poll from YouGov Plc found that three-fourths of Germans say the chancellor hasn’t done enough to fend off driving bans. So on Oct. 21, Merkel proposed a law to make it more difficult for courts to limit the use of diesels. “We should avoid driving bans wherever possible,” she said in a podcast.

Merkel’s flip-flopping on the issue illustrates her scrambling to shore up her waning influence on German politics. In national elections a year ago, her Christian Democrat alliance saw its share of the vote fall to its lowest level since 1949, and it took five months to cobble together a government, with the center-left Social Democrats. Since she started her fourth term as chancellor in March, Merkel has faced frequent squabbling in her coalition and a virulent challenge from the anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany, or AfD. In Oct. 14 elections in Bavaria, her bloc faced another drubbing, with the AfD reaching 10 percent and the Greens surging to 18 percent. The diesel issue “has been ignored for too long,” Finance Minister Olaf Scholz—whose Social Democratic Party saw its support in Bavaria fall by half—said at an engineering conference in Berlin. “We have to do something.”

The future of diesel has dominated the campaigning for Oct. 28 elections in Hesse—the state that includes Frankfurt. The issue has given a boost to the Greens, who’ve climbed above 20 percent in recent polls—just a few points behind the Christian Democrats and neck and neck with the Social Democrats. If either governing party suffers a convincing defeat in the western stronghold of centrist, middle-class voters, Merkel might face pressure to give up the leadership. And the Social Democrats could decide to quit the coalition rather than continue to be tarnished by their association with the chancellor. “Merkel has always postponed the issue” of cleaning up the auto industry, says Sören Bartol, a lawmaker from the Social Democrats responsible for transportation policy. “Now the public is furious, and this is becoming a political problem.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.