There Are Better Ways to Do Democracy

There Are Better Ways to Do Democracy

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The Brexit disaster has stained the reputation of direct democracy. The United Kingdom’s trauma began in 2016, when then-Prime Minister David Cameron miscalculated that he could strengthen Britain’s attachment to the European Union by calling a referendum on it. The Leave campaign made unkeepable promises about Brexit’s benefits. Voters spent little time studying the facts because there was a vanishingly small chance that any given vote would make the difference by breaking a tie. Leave won—and Google searches for “What is the EU” spiked after the polls closed.

Brexit is only one manifestation of a global problem. Citizens want elected officials to be as responsive as Uber drivers, but they don’t always take their own responsibilities seriously. This problem isn’t new. America’s Founding Fathers worried that democracy would devolve into mob rule; the word “democracy” appears nowhere in the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution.

While fears about democratic dysfunction are understandable, there are ways to make voters into real participants in the democratic process without giving in to mobocracy. Instead of referendums, which often become lightning rods for extremism, political scientists say it’s better to make voters think like jurors, whose decisions affect the lives and fortunes of others.

Guided deliberation, also known as deliberative democracy, is one way to achieve that. Ireland used it in 2016 and 2017 to help decide whether to repeal a constitutional amendment that banned abortion in most cases. A 99-person Citizens’ Assembly was selected to mirror the Irish population. It met over five weekends to evaluate input from lawyers and obstetricians, pro-life and pro-choice groups, and more than 13,000 written submissions from the public, guided by a chairperson from the Irish supreme court. Together they concluded that the legislature should have the power to allow abortion under a broader set of conditions, a recommendation that voters approved in a 2018 referendum; abortion in Ireland became legal in January 2019.

Done right, deliberative democracy brings out the best in citizens. “My experience shows that some of the most polarising issues can be tackled in this manner,” Louise Caldwell, an Irish assembly member, wrote in a column for the Guardian in January. India’s village assemblies, which involve all the adults in local decision-making, are a form of deliberative democracy on a grand scale. A March article in the journal Science says that “evidence from places such as Colombia, Belgium, Northern Ireland, and Bosnia shows that properly structured deliberation can promote recognition, understanding, and learning.” Even French President Emmanuel Macron has used it, convening a three-month “great debate” to solicit the public’s views on some of the issues raised by the sometimes-violent Yellow Vest movement. On April 8, Prime Minister Edouard Philippe presented one key finding: The French have “zero tolerance” for new taxes.

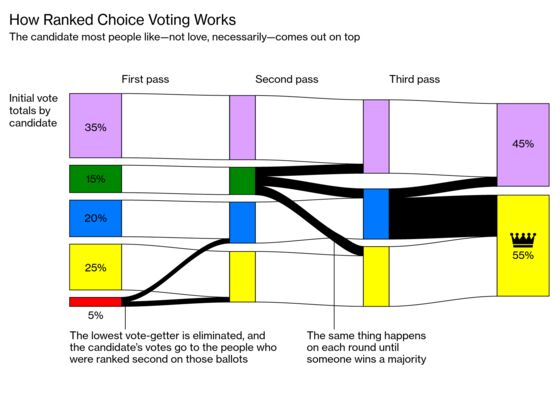

Another way to fix democracy is to change how people vote. Rather than have voters register a simple yes or no for a candidate, there’s growing interest in ranked choice voting, which allows them to express their full range of preferences. Voters rank everyone on the ballot, and if no one wins a majority of first-place votes, the candidate who got the fewest is dropped from consideration and his or her votes are redistributed to the other candidates based on voters’ second choices. This winnowing process is repeated until someone wins a majority.

The goal is to elect candidates who are acceptable to a broad swath of the electorate. Those in the running take care not to offend each other’s supporters. Australia has used ranked choice voting in national elections for a century. In 2018, Maine became the first U.S. state to use it for federal offices; San Francisco and Minneapolis, among others, use it for municipal elections. In 2013 candidates for mayor of Minneapolis linked arms after their last debate and sang Kumbaya. (Seriously.)

The U.S. Constitution’s framers tried to insulate government from mob rule by having senators elected by state legislatures and the president by members of an electoral college, who weren’t originally required to echo their states’ voters. Democracy gradually became more direct, with a surge in the early 20th century, when the Progressive movement brought women’s suffrage, direct election of senators, and a wave of state laws providing for referendums, ballot initiatives, and the like.

What the American system needs now is a third stage of development, journalist Nathan Gardels and investor Nicolas Berggruen argue in Renovating Democracy: Governing in the Age of Globalization and Digital Capitalism, a book coming out on April 30. In 2010 they founded the Think Long Committee, a bipartisan group working toward improving governance in California. In 2014, then-Governor Jerry Brown signed a Think Long-backed measure requiring public hearings on ballot initiatives. The new process led to a first-in-the-nation digital privacy act last year.

Democracy tends to work best at the local level, where people can engage face-to-face on issues that affect them directly. Thomas Jefferson wanted to place most functions in “ward republics” of a few hundred citizens. That’s not realistic today, if it ever was. But Jefferson’s desire to involve everyone remains relevant. Last year, Yale political scientist Hélène Landemore advised the French National Assembly on how to involve the public. She quoted the American civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois: “We must appeal not to the few, not to some souls, but to all.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.