The Vegetarians at the Gate

The Vegetarians at the Gate

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- During a busy lunch service in the cafeteria of one of Silicon Valley’s largest cloud-computing companies, the vegan chef Chad Sarno turned up a gas burner and slowly poured a bottle of white wine into a steel saucepan filled with chopped onion, capers, vegetable stock, and al dente linguine. He tossed the mixture with a flick of the wrist, lowered the heat to a brisk simmer, and added a handful of flakes of Good Catch, a plant-based tuna substitute made of chickpeas, soy, lentils, beans, and oil flavored with an algae extract. After letting the pasta absorb the sauce for a minute, he plated a snack-size portion for a petite, dark-haired woman named Maisie Ganzler, who was waiting at a corner table to taste the results.

Sarno, who founded Good Catch two years ago with his brother, Derek, was visibly anxious as he presented the dish. Ganzler is the head of strategy at Bon Appétit Management Co., a high-end subsidiary of Compass Group Plc, a catering giant that feeds more than a million people daily, including at Apple, Facebook, and Google. A nod from her would be huge for Good Catch, potentially bringing its food to the palates of some of the world’s most influential eaters.

Ganzler’s expression was inscrutable as she tried the linguine, followed by a salad topped with more of the imitation tuna, which has a taupe color not unlike that of the real thing. Then she smiled. When, she asked, could Bon Appétit get its first Good Catch deliveries? She was also interested in Numu, a no-milk mozzarella Sarno had melted convincingly onto a pair of margherita pizzas a half-hour earlier.

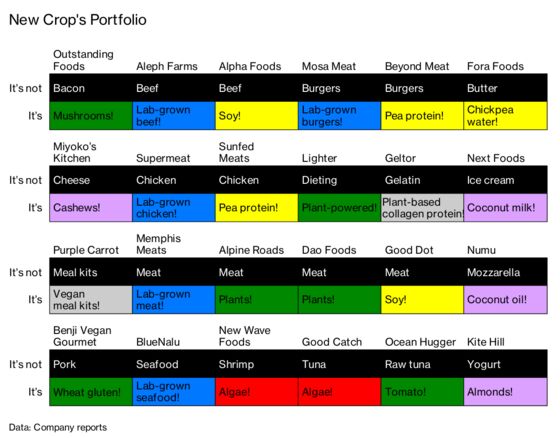

While Ganzler chewed, Chris Kerr, who’d organized the August tasting, was watching intently from across the table. Kerr is the co-founder and chief investment officer of New Crop Capital, a New York venture firm with stakes in 33 vegan food companies, including Good Catch, meal-kit producer Purple Carrot, and Beyond Meat, which sells pea-based burgers that “bleed” on the plate. As the locus of vegan eating shifts from musty whole-foods stores to, well, Whole Foods stores, Kerr has become a ubiquitous tastemaker, seeding promising companies, attracting additional investors, and matchmaking startups with food giants such as Cargill Inc. and Maple Leaf Foods Inc. that are determined to hedge against declines in meat consumption.

“We’re in a sweet moment right now—everyone’s paying attention. The dollars are telling the story,” Kerr says. “You can certainly make a footprint and partner with the right people to make it global quickly. That’s my big mission.” His company has about $60 million under management, and with backing from Thai businessman Dan Pathomvanich, he’s creating another vehicle, the $100 million New Protein Fund, which will invest in advanced manufacturing and distribution to help rapidly roll out products developed by New Crop-funded companies.

“He’s the godfather of this whole thing,” Sarno says of Kerr, who was Good Catch’s first investor. Last summer the startup raised $8.7 million in new funding from backers including PHW-Gruppe Lohmann & Co., one of Europe’s largest poultry producers, though it hadn’t yet sold a single box of ersatz tuna.

There’s plenty of demand for a piece of the plant-based action. The day before the Good Catch taste-off, Kerr had breakfast in San Francisco with billionaire investor John Sobrato to discuss possible deals. Then he drove across the Bay to meet with an executive at Rich Products Corp., the maker of Carvel ice cream cakes. Next he had a call with a high-powered investment representative that ran for so long, his car got towed.

To all of them, Kerr made the same overarching pitch: The vegan revolution is here, and there are fortunes to be made. His enthusiasm was probably only a little excessive. So-called alternative proteins are the fastest-growing segment of the food industry, and overall sales of vegan items in the U.S. rose 20 percent from 2017 to the middle of this year, reaching $3.3 billion, according to Nielsen. “We will be rich, no matter what,” Kerr told Rich Products executive Dinsh Guzdar, to whom he was talking up Numu.

Yet even as Kerr tirelessly promotes vegan eating, he’s exposing a tension at the heart of the boom. For decades, veganism has been rooted in the counterculture and in rejection of the animal-derived, heavily processed, sodium-laden pathologies of the modern food system. Yet for the diet to enter the mainstream, it will almost certainly have to be companies in that same food system, using many of the same practices, that bring it to mass-market scale. To go truly global, in other words, vegan foods must be financialized and industrialized. And Kerr wants to be the guy to do it.

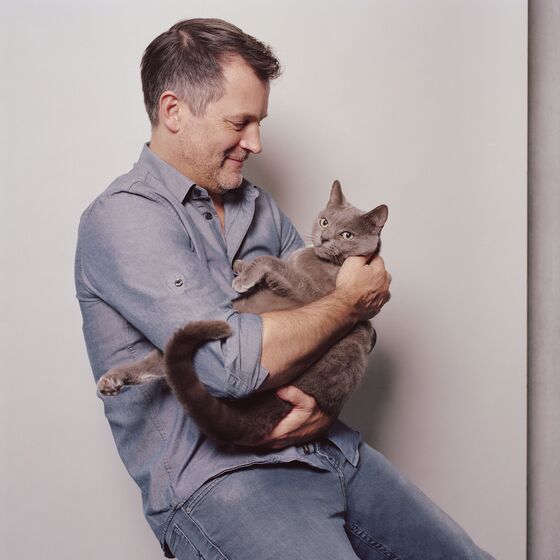

Kerr is 51, with a light stubble and salt-and-pepper hair. He tends to dress casually even for a venture capitalist, favoring slim-fitting jeans, New Balance sneakers, and a faded black hoodie depicting an elephant above the word “Herbivore.”

Like almost everyone else he knew growing up in Berks County, Pa., Kerr ate meat and plenty of it. Although his father was an antiques restorer and his mother a homemaker, his family kept a mix of cows, pigs, chickens, and ducks on their property for slaughter. Dairy farming was one of the main local industries, and Kerr helped milk a neighbor’s cows.

After college at Babson, outside Boston, he managed medical-waste businesses in New York and Maine and a software development company in Colorado. In 1999 he reconnected with his now-wife Kirsti, a high school crush who’d been a vegan since before they met. They moved in together in 2000, and she began nudging Kerr toward books and documentaries about animal welfare. His epiphany came after reading Ethics Into Action, a history of the animal-rights movement by the philosopher Peter Singer. “There are two types of people—those who’ve been born understanding what injustice looks like, and those who need to be shown,” Kerr said of his transformation. “Kirsti was born with it. I had to be shown.” She now advises Kerr on his New Crop initiatives and often accompanies him to evaluate investments. They have seven cats.

Only three weeks after Kerr resolved to go vegan, he met Wayne Pacelle, then a senior executive at the Humane Society of the U.S., at an event for the animal-rescue charity Farm Sanctuary. (Pacelle later became the society’s chief executive officer, but he stepped down in 2018 amid allegations of sexual harassment, which he denied.) Kerr was committed to his new lifestyle, but he complained to Pacelle that he missed cheeseburgers, croissants, pizza, and other animal-based favorites. He said he was thinking about investing in vegan brands to try, in a small way, to accelerate the development of tastier options.

Pacelle had a different idea: Why not do it with the Humane Society’s money? He eventually offered Kerr a job at the organization’s Washington headquarters, putting him in charge of a portion of its $200 million investment pool and giving him the curious title of head of private equity. His mandate was to move the society out of low-key mutual funds and into direct stakes in animal-friendly businesses. Kerr spent seven years in the role, investing in and advising a list of companies that grew to include Beyond Meat, imitation cheese manufacturer Miyoko’s Kitchen Inc., and the fast-casual chain Veggie Grill Inc.

Kerr couldn’t have known it at the time, but his niche was about to become much wider. Although diets that strictly avoid animal products have existed for at least a millennium, their modern conception dates to the 1940s, when English animal-rights activist Donald Watson coined the term “vegan” and founded the Vegan Society. (He also considered “vitan,” “benevore,” “beaumangeur,” and “sanivore.”) For a long time, the market for vegan products was essentially a rounding error. They were hardly the stuff of aspirational branding: First, remove from your diet dozens of delicious foods, then add a few parts sanctimony and a dollop of joylessness. Sprinkle liberally with sprouts and serve lukewarm.

But about 10 years ago, something changed. One of the first high-profile vegans was ex-President Bill Clinton, who cut out meat and dairy after a 2010 heart bypass, later boasting that he’d lost 20 pounds as a result. The diet soon caught on in Hollywood, and popular, sometimes scientifically unrigorous documentaries critical of the meat industry—Cowspiracy, What the Health, and others—proliferated on Netflix and rival streaming services. Meanwhile, Silicon Valley got in on the act, seeing an opportunity to disrupt historically tasteless foods. As the roster of A-listers who’d sworn off animal products grew to include Jessica Chastain, Benedict Cumberbatch, and Ava DuVernay, going vegan became almost aspirational. Beauty blogs now refer uncritically to something called a “vegan glow.”

Veganism seems all but tailor-made for the current cultural moment, perfect for generating techno-optimism among producers and Instagram envy among consumers. The branding no longer evokes an incense-scented health food store with an alarming selection of herbal laxatives, but enterprises such as the cheerful By Chloe chain, co-founded by chef Chloe Coscarelli, which offers pricey, veggie-only burgers, bowls, and cakes from bright storefronts in neighborhoods such as New York’s West Village.

Concern about climate change has also given the vegan movement additional energy. After the utility sector, agriculture—and particularly the cultivation of animals for food—is by far the largest source of global carbon emissions. As diners in developing countries become affluent enough to regularly eat meat, those emissions will continue to climb unless something changes dramatically. The urgent need to avoid roasting the planet only strengthens Kerr’s pitch.

Kerr departed the Humane Society in 2014 frustrated, by his account, that its board couldn’t approve investments quickly enough. He created New Crop the next year, with funding from individuals he describes as “wealthy backers who wish to remain anonymous.” Most of its eight employees, a mix of Wall Street veterans and environmental types, are vegetarian or vegan. From the start, Kerr was determined to be more hands-on with the companies he invested in than most venture capitalists, reasoning that few vegan entrepreneurs had experience rapidly scaling up their operations. It’s a philosophy he takes to what other investors might consider extremes: In addition to his other responsibilities, he serves as co-CEO of Good Catch.

Although most of New Crop’s investments are in the standard precincts of lab-grown or plant-based meat substitutes, others are more offbeat. Kerr is particularly excited about the prospects for Fora Foods, a maker of “dairy-free butter”—it uses coconuts and the protein-rich water left over after chickpeas are boiled for hummus—that he’s pitching it to brioche manufacturers in France. He’s similarly stoked about a startup called Geltor Inc., which is producing a substitute for gelatin by programming microbes with the same genes that give the traditional kind, derived from animal bones, its unique consistency. “I would argue,” Kerr said, “there’s nothing more disgusting we eat as humans than gelatin,” which is used in marshmallows, yogurt, and candy. “Nobody on the planet cares about whether it gets replaced, because it’s not eaten for flavor.”

But it’s Kerr’s collaboration with the Sarno brothers that probably best speaks to the commercial potential of novel vegan foods. About a decade ago, Derek Sarno, the elder of the pair at 48, was working as a chef and restaurateur in New Hampshire when his longtime partner was killed in a car accident. Devastated, he retreated to a Buddhist monastery in upstate New York. The monks instilled in him a passion for animal welfare, and he left determined to give up meat and fish.

Sarno met Kerr at an animal-rights event in Los Angeles not long afterward. With Kerr’s encouragement, Sarno and his brother Chad—also a chef in his 40s, and a vegan since his teenage years—in 2015 founded Wicked Healthy, a purveyor of animal-free cookbooks and prepared foods. Kerr came on board as an investor and adviser, with the official title of “strategy sensei.” Wicked Healthy traded heavily on the Sarnos’ personal spin on vegan living: both brothers are toned, photogenic, and inked; Derek’s arms are sleeved with budding flowers and dragon scales.

The company got noticed quickly. Shortly after Wicked Healthy was created, it entered talks with Tesco Plc, the U.K.’s largest grocer, about a distribution deal for its Wicked Kitchen food line. (The early discussions were code-named Project Mildred, for the name Derek gave to an injured squirrel he once rescued in Portland, Ore.) Tesco was intrigued enough to agree to an exclusive five-year deal to sell Wicked Kitchen products in the U.K. and to hire Derek as its first director of plant-based innovation.

Tesco began stocking Wicked Kitchen items, such as carrot-spiced wraps with fake pastrami and a cheeseless mushroom sourdough pizza, in January 2018. In April the grocer announced that its first-quarter earnings had jumped by almost a third, an increase attributed in part to Wicked Kitchen. Sarno, who’s much more focused on food than finance, says his lawyer called afterward to tell him, “Derek, I know you don’t know what the f--- this means, but mention it in future negotiations.”

Tesco has an option to purchase the Wicked Kitchen brand outright at the end of the five-year contract. It’s a strong possibility. Dealmaking in the vegan industry has reached a frenetic pace. In January, Goldman Sachs Group joined a $65 million investment round for Ripple Foods, which makes a milk substitute from yellow peas; Microsoft founder Bill Gates, UBS, and Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund are backing Impossible Foods, creator of the plant-based Impossible Burger. Tyson Foods Inc. and billionaire Richard Branson now own a piece of “cultured meat” pioneer Memphis Meats, in which New Crop was a seed investor.

Outright acquisitions are proliferating, too, with Nestlé SA in 2017 taking over Sweet Earth Foods, which sells sandwiches with ingredients such as “Harmless Ham” and “Benevolent Bacon.” Maple Leaf, Canada’s largest meatpacker, recently bought Field Roast Grain Meat Co., which makes vegan sausages.

But with the same companies that dominate the existing food business moving to do the same with vegan products, some activists and nutritionists fear there’s a real risk of replicating many of that industry’s existing problems. The most obvious pertain to health. In principle, an animal-free diet can be more healthful than a carnivorous one—lower in cholesterol and calories and higher in fiber, magnesium, and several key vitamins (though nutritionists often recommend supplements to make up for deficiencies in others). But many of the most heralded vegetable-based products may be worse for you—or at least not much better—than their conventional equivalents. The Impossible Burger, made from wheat, soy, and potato, is more calorific than a lean beef patty and contains seven times more sodium, though no cholesterol. One tablespoon of coconut oil—the main ingredient in Numu, the New Crop-backed mozzarella substitute—contains almost the recommended daily limit for saturated fat.

The underlying concern is that the rise of Big Vegan will give plant-based eating a hard push in the direction of so-called hyperpalatable foods, calculated to encourage addiction by flooding the brain with the pleasurable effects of fat and salt. New food technologies can undoubtedly make some difference, but there’s a good reason that vegan diets, which in their traditional form tended to be light on flavors humans are hard-wired to desire, have never before been popular.

Some longtime vegans are conflicted in other ways about the trends Kerr is working to supercharge. One of his first initiatives at the Humane Society was to develop an alliance with Daiya Foods Inc., a Canadian manufacturer of cheese imitations made from cassava and arrowroot. Kerr advised the company on distribution, helping to engineer a deal with Whole Foods. Sales soared, and in 2017, Japan’s Otsuka Holdings Co., a pharmaceutical producer with a long history of animal testing, agreed to buy Daiya for $325 million. Outrage followed, with some vegan grocers removing its products from their shelves and a Change.org petition demanding that the company “consider accepting less profit rather than filling their pockets with blood money.”

One of the stores that pulled Daiya products was Orchard Grocer, a vegan deli on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The shop made the decision after consulting with customers, according to general manager Nora Vargas. “I have conflicting feelings about it,” she says. Companies that rely on animals are “enemy No. 1. But on the other hand, it’s money that’s helping veganize the world.”

Kerr rejects the notion that the movement is selling out by allying with companies that conduct animal testing or, for that matter, with Big Food players that many vegans believe are essentially in the torture-and-murder business. Instead, he argues that vegan businesses should be willing to accept help no matter where it originates, especially if it’s useful in getting to scale quickly. The Daiya deal, Kerr remarked, was “them saying, ‘I like what you’re doing.’ And this maniacal fringe is there saying, ‘You don’t get to like what I’m doing. I don’t agree with you.’ We don’t want to fight with industry—we want to be inside their system. They can make these things grow so much faster than we can.” As long as big incumbents are willing to put up the cash for plant-based ideas, he says, “I don’t have to judge their values.”

Kerr is correct that despite the sector’s rapid growth, many vegan brands remain too small to produce their own products in commercially relevant quantities. Rather, they rely on relatively anonymous manufacturers to do the actual work of turning plant matter into an appetizing snack that may look and taste nothing like its original ingredients. One of them is Brecks Co., a British specialist in meat-free proteins that occupies the hangars of an abandoned airfield in the rolling hills of North Yorkshire.

Kerr visited this summer to look in on Brecks’s plans to make fake tuna for Good Catch, which was renting production facilities from a university lab. Before escorting Kerr on a tour of his factory, Brecks founder, James Hirst, explained that the company would deploy something called a high-moisture extrusion machine for Good Catch, optimizing it to transform a slurry of legumes and pulses into something approximating aquatic flesh.

“This is bringing tears to my eyes, man,” Kerr told Hirst admiringly upon seeing the contraption, which resembles a cross between a rocket engine, an MRI scanner, and an antiaircraft cannon. It operates at about 200F, rendering the mixture of plant proteins, water, and flavorings into a state reminiscent of molten plastic. The hot mass is then cooled, becoming a solid that, when divided into flakes, takes on the fibrous texture of canned tuna.

The facsimile isn’t perfect: Rubbery and bland, Good Catch tastes the way real tuna does when you have a severe cold. And the industrial, automated process is hardly the farm-to-table stuff of vegan dreams. Then again, witnessing what happens on a pig farm would be considerably more disconcerting for the average consumer—a point raised by an executive from Samworth Brothers, a British pork concern, who was also on the tour.

It’s a type of production the industry will have to do a lot more of as it scales up to meet exploding demand. The number of vegans in the U.K., for example, has increased fourfold since 2014, to about 600,000, according to the national Vegan Society. Many more people are at least interested in cutting down on meat: about 55 percent of British meat eaters, researcher Mintel Group estimates. Similar trends have been observed in the U.S., and some advocates say governments, at least in certain countries, will eventually move to discourage meat consumption “in the exact same way they’ve taxed the internal combustion engine, in relation to its carbon footprint and environmental cost,” as Hirst puts it.

If all goes according to plan, Kerr will have established a dominant position long before then. After visiting Yorkshire, he returned to London for more meetings about other plans, including one to sell fake chicken to PHW, the German poultry producer, which kills about 350 million real birds each year. Also on the agenda were further distribution deals for Good Catch, which Kerr says has the potential to significantly reduce industrial tuna fishing.

Given his track record and the broader trends, it’s a good bet that Kerr will continue expanding what’s already a profitable niche for vegan foods. But it’s one thing to sell more vegetable proteins to the post-yoga brunch crowd. It’s quite another to accomplish what he says is his life’s goal: overhauling the global food system in a way that transforms our relationship to animals and gives humanity a fighting chance of slowing climate change.

Either way, Kerr stands to make a great deal of money. Flopped onto a leather sofa after his London appointments, though, he insists he isn’t merely an opportunist riding a lucrative trend. “Yesterday I was pretty much only thinking about business,” Kerr says. “But when I got home to Kirsti, that’s when I thought, Whoa, we’re going to save a lot of fish.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Campbell at mcampbell39@bloomberg.net, Jeremy Keehn

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.