With U.S. Help, Global Growth in 2020 May Recover a Bit From a Dismal 2019

With U.S. Help, Global Growth in 2020 May Recover a Bit From a Dismal 2019

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- To avoid a recession in the U.S. in 2020, households need to keep spending, peace needs to break out in global trade wars, and investors can’t get spooked—by the U.S. presidential election or anything else. It would also help if policymakers in Europe and China did their part to shore up growth, even though the tools they have to do so are limited.

It’s likely that all these things will happen. That’s why Bloomberg Economics is forecasting that the U.S. economy will grow 2% in 2020 as the record-length expansion turns 11 years old in June. It’s also why election models focused solely on the strength of the domestic economy are predicting a win for Donald Trump in November. After all, real incomes are rising, and unemployment is at a 50-year low.

But risks abound. That 2% figure would be the slowest annual rate of growth since Trump was elected, and it keeps getting revised down. This U.S. recovery is already the longest period of continuous economic growth since 1854. The odds may favor another year, but no one’s betting the farm on it.

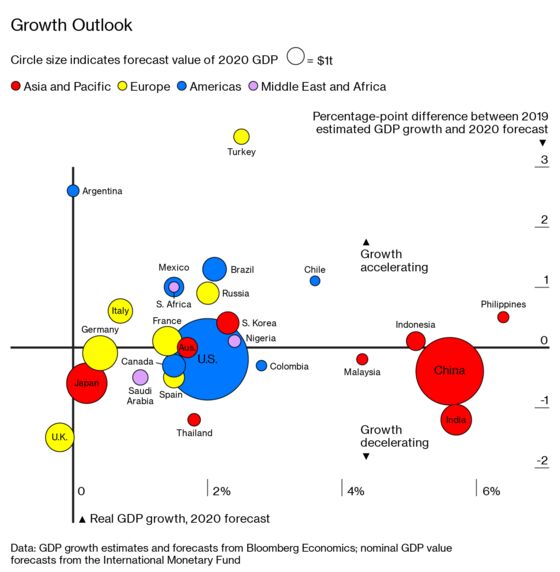

The biggest cloud hanging over the global economy is entirely of Trump’s making: trade. Surveys of business confidence and investment all began to turn south after the president started his trade skirmishes with China in early 2018. The slump in confidence and investment has led to a “globally synchronized slowdown,” according to Kristalina Georgieva, the International Monetary Fund’s new managing director, driven almost entirely by a slump in global manufacturing and trade. About 90% of the world’s economies grew more slowly in 2019 than in 2018, and growth overall was the weakest this decade.

The IMF expects global growth to be a bit stronger in 2020, thanks largely to emerging-market economies such as Brazil, India, and Russia doing better than in 2019. But Georgieva describes the global outlook as “precarious” and predicts that trade tensions will cut the growth of global gross domestic product by 0.8%—$700 billion—by the end of 2020. That’s roughly the size of the entire Swiss economy.

Trump has now slapped tariffs on $360 billion of Chinese goods. While that’s more than half of China’s total exports to the U.S., it’s only about 2.5% of China’s economy and a small fraction of total world trade. How do tariffs on this tiny slice of global output have such a seismic effect? The answer, in one word: uncertainty.

It’s not the tariffs that do the damage, it’s the suggestion that the rules under which the global trading system have operated for decades may be meaningless. “The risk premium now on business investment as a result of policy uncertainty is probably large enough in the U.S. to overwhelm the corporate tax cut,” says Glenn Hubbard, a professor at the Columbia Business School who was chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under George W. Bush. “The effect on investment and supply chains is real and pernicious.”

That’s a problem, because in the postwar period, the difference between average-length U.S. recoveries and the superlong ones has been a private investment boom in the later stages that helped to raise productivity—output per person—and gave the economy a second wind. That’s much less likely to happen when the growth rate of business investment has been falling since the trade wars began. Private nonresidential investment in the second quarter of 2018 was 6.9% higher than a year earlier. The latest figures show it growing only 2.6% over the past 12 months.

Trump likes to say that China is paying for the trade war. Yet economists tend to think that consumers bear the brunt of tariffs in higher prices, and that’s what research into the impact of tariffs has shown to date. But the biggest economic losers so far have been countries, such as Germany and Japan, that are highly integrated in global supply chains and dependent on global trade. Industrial production in both nations was lower in the third quarter of 2009 than a year earlier.

Bloomberg Economics expects Germany to end 2019 in recession and achieve growth of only 0.4% in 2020, less than half the forecast for the euro zone as a whole. In addition to trade worries, Japan’s economy will go into 2020 carrying the negative effects of a much-anticipated rise in the national sales tax, which is due to kick in at the end of October. Bloomberg Economics expects Japan to dodge a recession—but only just, with the economy growing by 0.2% in 2020.

There have been two other global manufacturing slowdowns since the global financial crisis: the first in 2012, during the euro zone crisis, and the second in 2015, amid rising concern about emerging-market economies. In 2012 the European Central Bank came to the rescue, eventually, by flooding the banking system with cheap liquidity and famously promising to do “whatever it takes.” What helped the global economy in 2015, in part, was a massive dose of Chinese stimulus.

Both the ECB and the Chinese authorities are in the picture today, but they’re unlikely to have the same impact.

The problem in the euro zone—as outgoing European Central Bank President Mario Draghi keeps pointing out—is that monetary policy is reaching the limits of what it can do. Interest rates are already negative on trillions of dollars of bonds, meaning investors are paying borrowers for the privilege of lending them money. The ECB cut rates again in October and agreed to restart quantitative easing—that is, buying bonds to help keep prices high and interest rates low. But ECB policymakers are deeply—and very publicly—divided on the effectiveness of these steps. Some contend that they distort financial markets so much that they’re actually making the situation worse.

What they most agree on is that fiscal stimulus—government spending—would be a far better way to support economic growth. But the countries that can afford to lay out the money aren’t the countries where the economy is most in need of a boost, nor are their politicians the most keen to spend. Bloomberg Economics expects a modest loosening of euro zone budgets, including Germany’s, in 2020. That’s unlikely to have a noticeable impact on growth.

What is different about 2020—in a good way—is that European politics is not, for once, expected to make the global economic situation worse. The new Italian coalition will probably reach a budget deal with the European Union. Only a few months ago, Italy looked set for a new government led by the populist Matteo Salvini, who might well have relished a costly showdown. Investors have shown their relief by pushing the Italian government’s cost of borrowing to new lows. Elections in Spain and Portugal are also likely to confirm the status quo.

Brexit—for now, at least—also looks less frightening to the rest of the world than it did a few months ago. Parliament’s approval of the general outline of Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s deal with Brussels reduces the risk of the U.K. crashing out of the EU without a deal in 2020. It also significantly reduces the risk of a U.K. recession.

Around the rest of the world, Turkey and Argentina are probably the biggest wild cards. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is determined to boost Turkish growth and will happily trash orthodox economic thinking to get there. He believes, for example, that cutting interest rates can lower inflation. That led to a currency crisis in 2018. Investors could get spooked again if the government resorts to unsustainable policies to achieve its lofty 5% growth target for 2020-22. The economy didn’t grow at all in 2019.

A victory for Alberto Fernández, the Peronist opposition candidate, in Argentina’s presidential election on Oct. 27 could cause some fireworks in Latin American markets and prompt a break with the IMF. It is not, however, likely to pose a threat to the system as a whole.

Could China come to the rescue? It may help, but it’s not going to carry a large chunk of the global economy on its shoulders as it did in 2016 and 2017. Bloomberg Economics expects the Chinese economy to grow 5.6% in 2020, the lowest rate since market reforms began in the early 1980s.

Chinese authorities are ramping up support for the economy. But their goal is to prevent a sharp slowdown, not to rev up growth to previous rates. They’re rightly reluctant to let too much cheap money flow to state-owned banks and companies that are already laden with debt. They’re also wary of using up all of their ammunition, with so much uncertainty about how much damage the country could suffer in the trade war with the U.S.

If you think this sounds worrying, you wouldn’t be alone. But the U.S. still has one great strength: the American consumer. “I cannot think of a time when the U.S. consumer has been in better shape,” said Federal Reserve Governor Richard Clarida in September. Debt levels relative to income are at their lowest in 40 years, the savings rate is high, and real consumer spending is growing at a rate of almost 3%.

Recessions tend to catch economists unawares, and the ones they do see coming often don’t happen at all. A few years back, many forecasters circled 2020 in their calendar as a likely time for a downturn. Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics Inc., warned in early 2018 that 2020 “is the real inflection point. ... It’s going to take some real good policymaking and some luck to avoid a recession.” Back then, Carl Riccadonna, Bloomberg LP’s chief U.S. economist, also predicted that the economy in 2020 might be “poised for a bumpy ride.”

With U.S. interest rates no longer at rock bottom and the sugar rush from the Trump tax cuts all used up, the fear was that the recovery might simply hit a wall. Instead, it has run into a thick fog of policy-induced uncertainty that’s making it difficult for businesses to plan ahead. But the private sector is still adding jobs, and the almost 80% of the U.S. economy that isn’t bound up with manufacturing and global trade is growing at a decent clip.

The business community might be spooked by Trump’s trade wars, but so far American households are not. As long as that continues to be true, the U.S. should avoid a recession in 2020. But there’s not a lot of room for error.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Eric Gelman at egelman3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.