The Trump Administration Loves Issuing Sanctions, Not Enforcing Them

The Trump Administration Loves Issuing Sanctions, Not Enforcing Them

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Since Donald Trump took office, the U.S. Department of the Treasury unit that implements sanctions has emerged as a high-profile foreign policy weapon, advancing U.S. interests by economically isolating Iran, Russia, and other hostile governments. The agency has blacklisted hundreds of people and companies around the globe and rolled out sanctions programs targeting everyone from foreign meddlers in U.S. elections to buyers of North Korean coal.

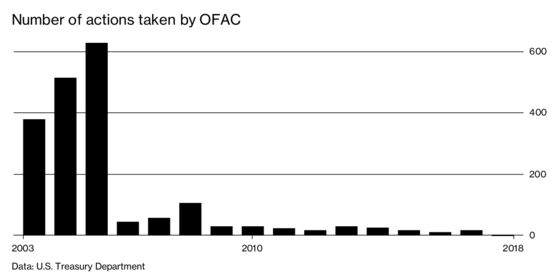

But with 2018 three-quarters gone, a crucial element of sanctions enforcement has all but disappeared: the actual enforcement. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control is on track to bring the lowest number of cases and penalties in 15 years, according to a Bloomberg Businessweek analysis of agency data. OFAC typically files dozens of cases a year against people and companies that breach sanctions orders, imposing hundreds of millions of dollars in fines. So far this year, OFAC has filed exactly one case. The haul: $146,000.

The decline has occurred in tandem with lighter enforcement at other U.S. agencies under the sway of a more business-friendly Trump administration. Regardless of the explanation, lawyers and former officials agree the change is stark. “You have an administration that loves using the sanctions powers afforded to it to forward foreign policy objectives,” says Dan Tannebaum, a former OFAC official and PwC executive who advises companies on sanctions compliance. “It would be even more impactful if you were not just revising and rolling out new programs, but enforcing violations for existing programs that are out there. All they’re doing is implementing, and not really enforcing.”

During the Bush administration, OFAC regularly issued hundreds of citations a year, with fines of typically a few thousand dollars apiece. The Obama administration changed its approach in 2009 after authorities detected a widespread practice among blacklisted countries of using European banks to process transactions through the U.S. The number of cases shrank, but the fines grew—sometimes reaching hundreds of millions of dollars.

Both the number of cases and the size of fines have generally been falling since 2014, when a wave of major sanctions-violation cases wound down. That year the agency filed 23 cases and imposed $1.2 billion in fines. The sole enforcement case filed by OFAC in 2018 was against Ericsson Inc. and its U.S. unit, involving telecom services it provided to Sudan. Because Ericsson reported the violation itself, it secured a discount on its penalty to below the minimum threshold OFAC could seek under the law. The drop in enforcement actions is “not indicative of any change in policies or priorities,” says a Treasury spokesperson. “Enforcement continues to be a high priority for OFAC.”

Rather than attribute the decrease in enforcement to a lax attitude, former officials point to factors including staff turnover, distracted leadership, and the complexity of the cases, which take years of painstaking investigation to build. Enforcement, policy, and blacklisting designations are each handled by a different part of the sanctions apparatus, but to bring a case ultimately requires the involvement of top officials within OFAC.

“There’s an inevitable bottleneck,” says Sean Kane, a former OFAC official who’s an international trade lawyer at law firm Dechert. “OFAC has been asked to do more than ever in the last year, on Russia, Iran, North Korea, so bottlenecks will naturally slow you down.” That’s been further complicated by recent departures from the enforcement staff and the counsel’s office, according to people familiar with the matter. Vacancies have gone as high as the associate director for enforcement and compliance, who helps oversee the division.

Some large-penalty cases have lingered in the pipeline for years, including one against French bank Société Générale SA, which says it’s weeks away from finalizing a penalty agreement. Others have been largely completed, but OFAC is holding off on announcing the results until November, to coincide with the reimposition of sanctions on Iran, according to one person familiar with the matter.

John Smith, director of OFAC until he left for private practice at Morrison & Foerster in April, says the drop-off in cases is a subject he often gets questions about. He says the recent dearth is an anomaly and expects the numbers to revert to more normal levels over time. “It would be a mistake to assume that OFAC has become less aggressive with respect to enforcement of economic sanctions,” Smith says. “That is particularly true in this administration, which has indicated publicly and vigorously that it intends to enforce the sanctions to the maximum extent possible.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.