The State With the Highest Suicide Rate Desperately Needs Shrinks

The State With the Highest Suicide Rate Desperately Needs Shrinks

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- 1. The mental health unit inside the Glendive Medical Center is dark, and when Jaime Shanks declares that a light switch surely must be around here somewhere, a faint echo chases the words down an empty hall.

“Here it is,” she says. The lobby flickers into clear view. “As you can see, everything is state-of-the-art, and it’s just a gorgeous facility.” She approaches a window and motions to the greenery beyond. “And isn’t this beautiful? A little courtyard you can look out on.” She admires it for a moment. “They didn’t want an atmosphere that felt too institutionalized. The colors all around, if you notice, are very warm.”

Behind a nurses’ station, a dry-erase board says that today is March 30. It’s actually late June. For three months the unit has been dormant, lights out. Shutdowns are hardly unusual; sometimes they last years. Since its grand opening in 2002, this unit—the only place in eastern Montana where a person with a mental health emergency can be admitted for inpatient care—has languished in a state of desertion more often than not.

The problem isn’t a lack of demand; Montana is cursed with the highest suicide rate in the nation, and it’s higher in this predominantly rural part of the state than in any other region. During the rare times when the unit is up and running, the supply of incoming patients is predictably, and sometimes frantically, consistent. The problem here is staffing. Administrators can’t find anyone to run the place.

Last fall, after years of fruitless recruiting drives and ad placements, the center finally snagged a recently graduated psychiatrist to oversee the unit. This spring, not long after the local newspaper celebrated her arrival, she quit. “I think maybe it was just a little too much for someone without experience to take on, and I don’t blame her,” says Shanks, who as marketing director is part of the recruitment team. “There’s such a huge need out here, and I can see the burnout in mental health providers that comes out of that.”

In much of America, and especially in places like Glendive, mental health care is a profession defined by severe imbalances. Overall demand for psychiatric services has never been higher, yet the number of providers has been falling since the 1960s. Psychiatrists are generally paid less than other medical doctors, they’re reimbursed by insurance companies at lower rates for many of the same services, and they absorb more mental stress than practitioners in most specialties. There’s been a slight uptick in psychiatric residencies in the past five years, but more psychiatrists are leaving the profession than entering it, and about 60% are over the age of 55, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

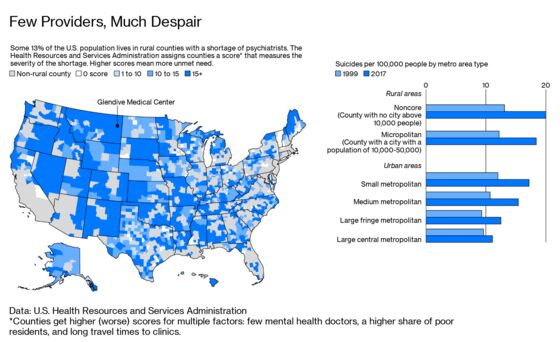

This is coming to a head at a terrible time. Suicide rates across all demographics in the U.S. are rising dramatically. Since 1999 the overall national rate has jumped 33%, and the spike has been especially sharp in rural counties—52% compared to about 15% in urban areas. Rural Americans are twice as likely as their urban counterparts to kill themselves, and many of the stresses they face are getting more intense. In the past year, farm incomes have dropped, and debt levels have risen at rates not seen since the farm crisis of the 1980s. Even so, today about two-thirds of all rural counties in America lack a psychiatrist, and nearly half lack a psychotherapist.

A woman who’s as intimately familiar with these dynamics as anyone in the U.S. lives a half-block from Glendive’s abandoned psych unit. Her name is Dr. Joan “Mutt” Dickson, and she was the unit’s founding director. After four years on the job, she hit her limit. Every single night, she says, she’d get at least two calls from emergency rooms or law enforcement agencies scattered across the region’s 17 counties, and she’d be expected to help them handle and harbor a troubled citizen who seemed truly suicidal.

“I’m tired now,” she told the Billings Gazette when she resigned in 2006.

After taking almost a year off to drive across the U.S. and clear her head, she returned to Glendive and opened a dual-specialty private practice—she’s a general family practitioner and a psychiatrist. She also works 20 hours a week as the regional psychiatrist for the Veterans Administration, and she serves—for a salary of $1 a year—as the medical director for the Eastern Montana Community Mental Health Center, a network of clinics.

“If you look at a map of the United States,” she says, “I am the only psychiatrist between Bismarck, North Dakota, and Billings, Montana.” That’s 400-plus miles. It’s like having one psychiatrist between New York City and Akron, Ohio.

2. Glendive is in a string of old railroad towns that cling to the banks of the Yellowstone River. The Burlington Northern still comes through daily, rattling past wheat fields and layered clay hills as it hauls coal from Wyoming to North Dakota. Just outside of Glendive, these hills undergo dramatic contortions, erupting into fossil-studded buttes, natural bridges, and gumbo pedestals. These are the badlands.

Most small towns here conform to a template: a hardware store, a Stockman Bank branch, a thrift shop, a casino (a bar with slot machines), and a local history museum of some sort. Glendive, with 5,000 residents, is bigger than most and commensurately curated: It has two full-time museums, the Frontier Gateway Museum, built around a collection of dinosaur fossils found nearby, and the Glendive Dinosaur & Fossil Museum, which presents paleontology within a Biblical, creationist perspective.

Follow Glendive’s main street past the museums, and you’ll come to Dickson’s office in the center of town. Her five-room suite shares the second floor of a 19th century building with a stationery store, a tattoo parlor, and the office of a public defender. The plush carpet softens the footfalls of Jemma, a 6-year-old black lab mix. Dickson doesn’t work with a nurse, an assistant, or a secretary. It’s just her and the dog.

Dickson, who’s 60, walks through the office with a short and choppy stride. Her hair is cropped and simply styled, and her uniform is likely to consist of a T-shirt, jeans, and dusty New Balance sneakers. If anyone calls her “Dr. Dickson,” the words never fail to clank in her ear. She much prefers people to call her Mutt, and almost everyone does. It’s a nickname with familial roots: Growing up, she was as short as her older brother was tall, so as kids they were always Mutt and Jeff, like the two mismatched friends from the old comic strip.

She recently picked up a microwave for $5 at an estate sale. Earlier, she’d picked up a TV for just a little more. Sometimes she keeps such finds, but more often she gives them away to friends. Two days ago, at another estate sale, she paid $5 for a giant mess of agate, a type of quartz that’s found in local river bottoms—two 5-gallon buckets, one coffee can, and a couple plastic bags full of rocks. She donated the lot to her friend Skinny, who wears a Make America Great Again hat and who likes polishing and cutting stone. Several times during her career, in lieu of payment for her medical and psychiatric services, Dickson has accepted turkeys and pies. Colleagues affectionately speak of her idiosyncrasies as if they’re a feature of the local landscape, as particular to the region as the peculiar rock formations outside of town.

“I think some people can’t figure me out,” she says. “But I’m just not one of those people who’s motivated by money.”

To narrow down exactly what did motivate her, she underwent years of far-flung self-exploration. She grew up in Scobey, a town of 1,000 about 20 miles from the Canadian border. She was salutatorian of her high school class, which in those days meant an automatic free ride to a public university in Montana—and that threw her career path off-kilter before it even began. “I really wanted to go to Wahpeton, North Dakota, to become a plumber,” she says. Instead she dutifully attended Montana State University at Bozeman for two years, until they made her declare a major. She promptly dropped out and went to work in New Mexico for a summer as a framer-finisher carpenter. Next came a stint driving trucks for a road construction outfit in Minnesota, where she took her first paramedic class.

She moved to Las Vegas to become an emergency medical technician. The 1980 MGM Grand hotel fire that killed 85 people happened on her second day on the job. She stayed on for seven years before curiosity—“I felt I just needed to know more about medical care”—drove her to enroll in nursing school. After holding down a full-time job while completing the course load, she became a registered nurse for the county trauma unit, and that led to a position in the medical unit at the federal government’s nuclear test site in Nevada. She eventually found herself on the medical crew of a Department of Energy ship that traveled to the South Pacific to drill core samples into the craters left by nuclear bomb tests in the 1950s. In the Marshall Islands, she mixed with the locals, liked them, and took a job as a nurse for a company that had a health-care contract with the Marshallese government. She stayed three years, doing everything from stitching up cuts to treating malnutrition to delivering babies and was, in everything but title, a full-fledged doctor. She made it official by returning to the U.S. to enroll in medical school at the University of Washington. She graduated in 1997.

She envisioned herself as an old-fashioned small-town doctor, like her family’s beloved Doc Norman in Scobey, who, during a house call years before, had stitched up her bleeding left elbow at the kitchen table. But the deeper she got into her studies and the more she talked with her teachers and colleagues, the more she realized that psychology was an unspoken component of every general practice: “Somebody comes in, and they say, ‘Doc, I’m tired all the time, and I’m gaining weight, I’m not sleeping well, and I just don’t feel good.’ When you talk to them, it’s clear they have depression.”

For some doctors, coaching patients through personal crises can seem a waste of the specialty they studied. For others, prescribing behavioral medicines can strain their own nerves. “They just don’t have the confidence,” Dickson says of colleagues who refer their patients to her for prescriptions they could easily handle. “They don’t want to touch it.”

Dickson embraced the dualities inherent in the profession by completing a double-residency in general practice and psychiatry. In a small town like Glendive, this gives her an enormously broad window into the lives around her, and sometimes it can seem as if she knows everything about all of her neighbors. She’s got a pretty good handle on who was abused as a child, whose marriage is on the rocks, who’s flirted with an addiction to painkillers, who’s skittering through a mid-life crisis. It’s the sort of knowledge that can apply pressure on a person. She has no colleagues to talk with about possible treatments, no one to commiserate with over coffee. The American Psychiatric Association used to have a special committee dedicated to rural mental health providers, and she belonged to it, but the group disbanded a few years back. “There weren’t enough of us,” she says.

The absence of professional models means that she has been forced to create her own makeshift code of professional standards, because the ones her urban counterparts follow simply don’t apply. “The ethics of psychiatry are very strict, as far as you shouldn’t be doing business with someone who’s a patient of yours, for example,” she says. “Well, if that were the case, I wouldn’t be able to have my car fixed, buy my espresso in the morning, have a hamburger at lunch….”

It’s a Monday morning, post-espresso, and she’s sitting at her desk. The dog is tirelessly angling for her attention, dropping a squeeze ball in front of her on the desk, staring at her expectantly. Without looking away from the screen, Dickson tosses the ball into the waiting room; Jemma chases it, brings it back. Dickson absently humors the dog as she reads her screen, tossing the ball again and again, until her phone rings.

She says hello and instantly recognizes the male voice that comes through the speaker—a longtime client, one of hundreds who’s unafraid to call when life seems to be taking an unhealthy turn. “Oh,” he says, drawing a deep breath, “am I glad to hear your voice. I’m kinda jammed up here.” She takes him off speaker, and her first informal consultation of the week begins.

3. Dickson recently surveyed her patients to see why they thought this region, out of all the places in America, had become a hot zone in the suicide epidemic. Many blamed the Native American reservations, which they associate with addiction and despair. Those populations do, it’s true, have unusually high rates of depression and suicide, but Dickson challenged the answer as insufficient; even if you excluded those areas, the state’s suicide rate would still be among the nation’s highest. Montana’s Department of Public Health and Human Services last year reported a 2017 survey that suggested about 15% of all seventh-and eighth-grade students in the state had attempted suicide one or more times in the preceding 12 months. (Among Native American students, the figure was slightly higher, at 18%.) It’s a frighteningly high number and helped spur new outreach programs in the schools, but the suicide problem is even worse among adults. The average suicide victim in Montana is a middle-aged white male.

It’s impossible to pin down a primary cause, or even a set of them, but rural isolation is often fingered as a culprit. Suicides are worse here in the winters, supporting the hypothesis: For several months of the year, the region is gray, snowy, and bitterly cold, and the social pulse, metabolically subdued even in the summer, slackens noticeably. But isolation is nothing new here. Way back in 1893, a writer for the Atlantic Monthly observed that the “silence of death” cloaked the desolate landscape west of the Dakotas, and that “an alarming amount of insanity” haunted the pioneers who chose to homestead there.

When Dickson asked one of her longtime family practice patients why he thought there was so much mental illness in the area, he dismissed the notion outright. “First, you gotta believe that mental illness is a thing,” he told her. “And I don’t. You just get over it and move on.” It was a succinct distillation of the “cowboy up” gospel—a local creed that reveres rugged self-reliance. Although the mindset certainly has its virtues, Dickson has learned that few of them intersect with the world of mental health care. The prevalence of the attitude is one reason her office is in a multi-use building and not a standalone structure, so her patients can park their cars outside without giving away that they’re seeing a shrink. It’s also why the Glendive Medical Center psych unit, during those rare times when it’s operational, allows outpatient clients to enter through the back door, where their friends and neighbors are less likely to spot them. “Most people I know would tell people they have chlamydia before they’d tell someone they had a mental illness,” Dickson says.

The man who said he doesn’t believe in mental illness was a farmer, the line of work that still drives eastern Montana’s economy. The region doesn’t get much rain—10 to 15 inches a year, about a third of the national average—making agriculture a nerve-shredding business. “It’s tough,” Dickson says. “People tend to drink a fair amount of alcohol when you don’t have many other sources of entertainment. Everybody has guns. You get the stress of a poor crop, of tariffs, and you can’t sell your wheat for what it costs to put in the ground. Cattle prices may or may not be good. The bank’s knocking at your door. Your kids are moving away because of brain drain. So people a lot of times tend to deal with it with a single bullet.”

Money is always high on the list of mental stressors, and more often than not, when people list possible causes for the spiking of the suicide rate, the economy dominates the discussion. Since the Great Recession of 2008, the nation’s economic recovery has been concentrated in what the Department of Commerce defines as metropolitan areas—counties with a central city of at least 50,000 and the neighboring counties that are economically dependent on them. According to David Swenson, an economist at Iowa State University who specializes in analysis of the rural economy, these urbanized zones make up about 36% of all U.S. counties, but they enjoyed almost 99% of all job and population growth from 2008 to 2017.

“There’s more and more farm stress, and imagine if that’s your livelihood,” says former Democratic Senator Heidi Heitkamp, who represented neighboring North Dakota from 2013 to 2019. “It may be something you’ve been doing for your whole life—it’s not like you can just go out and look for another job running another farm.” Heitkamp this year co-founded the One Country Project, which aims to increase political engagement with rural communities, and she believes rural mental health, particularly among seniors who feel isolated and alone, has become a crisis. “There’s the stigma, but the solution to that is to embed mental health into health care,” she says. Offering basic behavioral health services at community health centers is one way to do that, she says. “And more primary-care physicians are starting to be trained to do more behavioral health.”

It’s not just doctors. Across rural America, agricultural extension offices have begun providing basic mental health training to rural lenders, farm-equipment dealers, and other agricultural professionals to teach them to recognize and respond to symptoms of depression among their clients.

The internet might collapse distances and make the world smaller, yet sometimes it feels like the opposite applies in a place like Glendive. About a century before Amazon.com, the Sears, Roebuck catalog was a retail lifeline for rural America. But throughout most of those decades, small, far-flung communities generally could depend on at least a few local retail outlets to provide the basics. That’s not always true today. In 2017, Glendive’s last department store, a Kmart, closed, part of a nationwide constriction blamed on the rise of internet retailing. That closure meant the closest general retailer was a Shopko in Sidney, about 50 miles away. In June, Shopko Stores Inc., a discount chain with stores in 24 states, went bankrupt, abandoning all of its locations.

The day after Shopko folded, a few of the therapists in Glendive’s branch of the Eastern Montana Community Mental Health Center—where Dickson serves as medical director—speculate that the news would add a little more stress to the lives of the people they see. “All the Shopkos are going down,” says Pam Liccardi, the clinic’s substance abuse counselor, shaking her head. “Every one of them.”

“So now we don’t have a place to go to buy clothes,” observes Al Heidt, a retired therapist whose wife, Cindy, still works at the facility. “You can’t buy underwear in Glendive.”

“Well, yeah, you can,” Liccardi says. “At the hardware store. If I was willing to wear men’s boxers, I’d be in business.”

There’s still Amazon, of course, and a resale shop downtown. But consider the added pressure the closures put on Sam Hubbard. He’s the vice president in charge of operations at the Glendive Medical Center, which means he’s in charge of filling the vacancies in the psychiatric department. Here’s the job advertisement his hospital sent out to the wider world after its psychiatrist quit this year:

Welcome to Glendive, Montana! Outdoor enthusiasts will thrill to almost limitless possibilities around Glendive. Imagine watching the Milky Way nightly and counting shooting stars as you fall asleep; quiet so deep you can hear your soul relax; hunting or just having a staring contest with wildlife. The Yellowstone River, the nation’s longest untamed river, starts in Yellowstone Park and flows through the heart of Glendive. It’s a great source of recreation, agate hunting, and paddlefishing … .”

How could it be so hard to attract mental health professionals to such a place? When I asked a version of that question separately of Dickson and Shanks, the hospital’s marketing director, their instant responses were word-for-word copies: “Because it’s 70 miles to a Walmart.”

4. While the Glendive unit remains unstaffed, anyone in eastern Montana who is suicidal and needs inpatient mental health care will likely be sent to the Billings Clinic. For the towns tucked into the farthest corners of the region, that’s a five-hour drive.

“We’re hanging by a thread some nights,” says Melinda Truesdell, who runs the 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. shift at the clinic’s Psychiatric Stabilization Unit. “It’s all these little towns.” The clinic regularly admits 20 to 25 patients a night. The task is mental triage—guiding patients toward something resembling equilibrium, so they might be released in 24 hours or so to seek other, longer-term solutions. “It’s a revolving door,” she says. “We bring people in, and we’ll get them propped up and stabilized. But once they leave our doors, they’re going right back out there.”

The suicide problem in Montana has caught the attention of its lawmakers. At both the state and federal levels this year, they’ve introduced bills to start more prevention programs in schools and community centers. But last year, the state legislature cut funding for exactly the sort of case management the patients who are released from the Billings Clinic depend on. This year, Governor Steve Bullock, who’s also a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, restored some of that funding, but mental health advocates in Montana say the fallout has lingered.

“We have people who are admitted to us who say they’ve been trying to get on waiting lists to be seen by case management for weeks,” Truesdell says. It’s a common complaint across the country: Hospital emergency departments have been forced to bear the brunt of the escalating shortage of psychiatric services. The number of patients admitted for psychiatric services jumped 42% during a recent three-year period, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Truesdell is from Glasgow, Mont., one of the little towns her unit absorbs when the Glendive facility is down. She’s a mental health nurse practitioner, which means she has the authority to prescribe medications. This makes her a particularly valuable regional asset. She says no one near Glasgow—150 miles from Glendive—is willing or able to prescribe antidepressants or other mental health medications, so she takes it upon herself. Every month, the Eastern Montana Community Medical Health Center flies Truesdell to Glasgow to spend a couple days prescribing medications for the locals.

The clinics can afford the flights, which are government subsidized and cost less than $50 each way. But Truesdell knows that even such a modest expense could someday be targeted by cost-cutters. “Everyone’s answer to these sorts of problems is tele-psych,” she says, referring to the practice of treating patients remotely, via internet-based video consultations. “But it’s a Band-Aid. It’s treated as this panacea on a grand scale for rural medicine, but it’s falling way short when it comes to mental health.”

A growing body of evidence shows that televisual consultations between rural patients and doctors can be effective—or, at least, significantly more effective than no treatment at all. But Truesdell and others who’ve administered such treatments are quick to identify their shortcomings. “You don’t feel the energy of that person, you don’t know the demographics, you don’t know the families—it’s just not enough,” she says.

Even so, tele-consultations are beginning to transform mental health care throughout rural America. Dickson spends 20 hours a week providing psychiatric services at the local VA office, where about 85% of her sessions are done remotely. Inside her windowless office at the VA, a large monitor that’s propped up on packages of printer paper sits behind her regular computer screen. “Let’s see who’s on my list,” she says on a recent Monday, scanning her schedule of appointments. She’s to see one patient from Bozeman, another from Great Falls, and another from Helena.

The case file of the woman in Helena indicates that she’s bipolar and developed PTSD after being sexually abused while in the military. The woman hasn’t been on her meds since she moved to Montana from another state about a year ago, and in her session she asks Dickson to restore her previous prescription. Dickson would love to, but the medication isn’t listed by the Montana VA as a first-line drug. She’d have to prescribe a different, less costly, generic. Dickson says she and the patient most likely will wait for the drug to fail to work, and then they’ll try to get approval for the drug of choice, which they know effectively treats her.

The woman on the other end of the video call, like everyone else who undergoes a remote consultation, isn’t seeing Dickson from her home. She’s had to travel to a clinic to access a nurse-supervised computer—the only kind approved for tele-health consultations. A patient Dickson treats through the VA travels 110 miles to reach the nearest supervised computer screen.

5. Dickson could spend all of her time seeing psychiatric patients if she wanted to. But that’s what she was doing in 2006, when she burned out and had to spend a year on the road to clear her head. So she’s more selective in her private practice. It’s important, she says, to guard some of her time for herself—for hiking in the badlands, for dinners with friends, for treasure-hunting at auctions.

For general, family-practice consultations, she charges a flat rate of $40 for a half-hour session; for psychiatric work, the rate is $200 for a first-time customer and $100 for a follow-up. She doesn’t accept insurance plans for either type of service, because she says she’d spend all of her time fighting for reimbursement if she did. She’d have to hire an employee just to deal with the paperwork.

Meiram Bendat, a California attorney who specializes in helping mental health patients litigate claim disputes with insurers, empathizes with her. “No sane provider who has better options would want to participate in an insurance company network under the way these services are being rationed in 2019,” he says. The situation is so dire for mental health providers, he says, that even in areas where there are plenty of practitioners, patients needing services often end up on long waiting lists. “We hear all the time from patients in Northern California that even in San Francisco they can’t see psychotherapists or psychiatrists, and I can assure that there is no shortage of practitioners in those areas,” Bendat says. “What there is, though, is a shortage of people willing to participate in insurance company networks and panels, and that’s largely driven by the paltry reimbursement rates that insurers are willing to pay for mental health services.”

Dickson likes to cast her decision to keep insurance companies at arm’s length as a part of a self-care routine, one she emphasizes is a key reason she’s still in the business while so many colleagues have left the field. She’s seen how occupational pressure can undermine the mental health of rural providers, and monitoring her own well-being has been a priority from the very beginning of her career, thanks to an extremely painful lesson in her third year of medical school.

Her older brother—the Jeff to her Mutt—was a physician, too, and the job was everything to him. “That was his identity, completely,” she says. After practicing in Oregon, he returned to Montana to open a rural practice in Glasgow, the community Truesdell now visits once a month by plane. There, his life unraveled.

After a rough divorce, he began to self-medicate and became addicted to prescription drugs. The state board of medicine busted him for writing prescriptions to himself. “He’d already lost his marriage, his relationship with two kids, was on the verge of bankruptcy, and when his identity as a doctor was threatened, well… .” The state board, she says, confronted him on a Friday, giving him the option of losing his license or undergoing treatment. Then they left him alone for the weekend. On Monday morning, he didn’t show up for treatment. “He suicided,” Dickson says.

Last year her sister, the only other surviving member of her family, was diagnosed with leukemia. Dickson considered temporarily moving to Colorado to take care of her. She didn’t want to abandon her patients in eastern Montana, but she felt strongly that neither she nor her patients should be under the illusion that she’s personally responsible for the mental health of a 48,000-square-mile swath of the rural West.

Dickson had vowed to avoid falling into the trap of getting wrapped up in her own professional identity, even if she was the only person in eastern Montana left in that profession. So early last year, the last psychiatrist moved away. In an email explaining her departure to her patients, she wrote, “Being a doctor is what I do, but it’s not who I am.”

She’d always known it would be a temporary relocation, and she returned six months later, after her sister’s health improved. When she reopened her office, demand for her services was as high as it had ever been, as was her conviction that she was exactly where she needed to be. She guesses she’ll probably live and work in Glendive until the day she dies.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Ferrara at dferrara5@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.