The Small Dealers Shaping the Vintage Watch Business

The Small Dealers Shaping The Vintage Watch Business

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- There’s a stereotype in the world of vintage watches, thanks to a classic cartoon trope. A shady man in a brown trench coat and a hat fit for a gangster approaches you on a street corner. “Wanna buy a watch?” he asks. He opens the coat to reveal several gleaming gold Rolexes dangling inside. They’re either fake or stolen or both. He’s like a greasy used-car salesman. You just can’t trust him.

“The old way of doing things was really speaking down to the buyer,” says James Lamdin, the founder of vintage watch dealer Analog/Shift LLC. “It was like, ‘I’ve got something you want. You want in? It’ll cost you this much. If you don’t want it from me, you’re no good to me.’ ”

These days, vintage watches have gone corporate. Businesses such as Lamdin’s entered the fray hoping to modernize a secondary market that had become fragmented across the internet and therefore untrustworthy. (The total preowned watch market is about $5 billion a year, according to Swiss research company Kepler Cheuvreux.) These newish businesses employ watch experts and restorers who comb the planet for rare finds to buy and sell at online storefronts or in appointment-only showrooms. The rarest and most expensive watches often end up at the world’s largest auction houses, including Phillips Auctioneers, Christie’s, and Sotheby’s.

Online watch forums and blogs, such as Hodinkee (a content partner with Bloomberg Pursuits) and Worn & Wound LLC, have stoked enthusiasm and fostered education. Watch aficionados want to know about the mechanisms inside, the design inspiration, and the history of a particular model. Meanwhile, watches have flourished on Instagram, where photos of beautiful timepieces have found a home in feeds alongside endless labradoodles and feet on beaches.

“That reach has put watches into a price level that never, if you asked me 20 years ago, I would’ve anticipated,” says Aurel Bacs, a famed auctioneer at Phillips who’s worked in the industry for almost three decades. In 2017 he auctioned off the most expensive wristwatch ever sold, Paul Newman’s Rolex Daytona, for $17.8 million. Bacs says the vintage watch market has become as established as those for art and automobiles, and thus it’s become a similarly sustainable alternative investment. “Certainly we’ve seen unbelievable growth in values,” says Eric Wind, owner of Wind Vintage. “The first vintage Rolex to ever sell for more than $1 million was back in 2011. Now it’s a common occurrence.”

What makes a watch qualify as vintage? There’s no catchall definition. Some consider it pre-1980s, before Rolex transitioned itself more squarely into the luxury sector. Specific aspects of design, such as a watch with acrylic crystals or tritium lume, may push a timepiece into the vintage category even if it was made later. Then there are the heritage brands now using design language from their own histories and producing watches that aren’t technically vintage but are often released as limited collectibles.

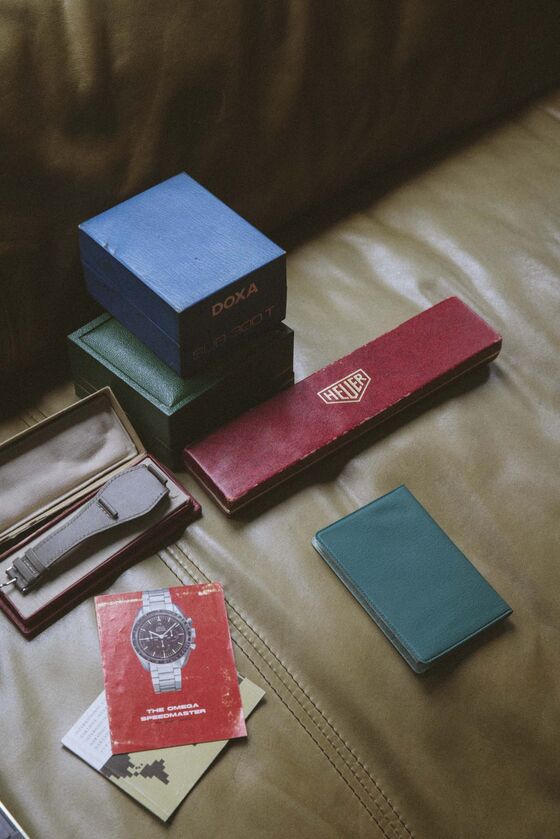

Beyond style and technology, classic timepieces can vary widely in cost based solely on condition. Two made by the same brand on the same day may sell for wildly different prices. One may be pristine, kept in a collector’s box for decades, and worth $500,000. The other may look fine but in fact be overly polished or restored by someone who didn’t know what he was doing, making it worth less than $25,000.

The question that vintage watch businesses are wrestling with as they grow is whether there’s enough space for all of them. EBay Inc. remains the giant for anything that’s resold, watches included. The auction houses are increasingly offering online-only sales at a lower price point than what goes under the gavel. And watch manufacturers including Audemars Piguet, Maximilian Büsser & Friends, and F.P. Journe have even begun buying, restoring, and reselling their own pieces to not miss out on this part of the market.

Like preowned high heels and clutches and even art by dead artists, the world’s supply of vintage watches is limited. These watches become older and rarer with each day, which is good for their value but provides a challenge for businesses that depend on foraging for fresh options to sell.

“Watches are the great talisman of days gone by,” says Lamdin, seated on a couch inside his watch boutique. “They’re a memento.” The 34-year-old started Analog/Shift out of a sublet bedroom in Harlem in 2012, when he was working in outdoor equipment sales. Armed with his cashed-out retirement savings, he started buying and selling watches and mustered a profit within the first month. These days his appointment-only showroom is in the penthouse on the eighth floor of a building in Manhattan’s Midtown East. Glass cases filled with watches sit in the living room, outfitted with shelves of dusty books. Lamdin rushes down the stairs from his office to sit on the couch and pour a couple of fingers of whiskey as an old movie plays on the TV. “A lot of the accumulated goodies in here are old–old clocks, old advertising,” he says. “We’re trying to create a little bubble in time.”

In Analog/Shift’s early days, it wasn’t so much whiskey and worrying about décor. Lamdin would knock on doors of owners and collectors to find watches. He now gets his pieces from pretty much anywhere—auctions, estate sales, some guy he meets at a bar. The best stuff comes from collectors because they’re already so picky, though Lamdin often has to pay a premium to get a coveted item off someone who loves watches.

Most items in the store and online cost $40,000 or less. Analog/Shift keeps its highest-end items, such as several military-issued Tudor Submariners from the French navy, early TAG Heuer Chronographs, and platinum Cartiers from the 1920s, off its website and locked in a vault. Lamdin doesn’t want to scare away newbie watch buyers with big-ticket listings, because he wants someone to feel comfortable picking up a $500 watch to get started. Those looking for the expensive items don’t often buy them on impulse on the internet, anyway.

For a select group of clients, Analog/Shift manages entire personal collections. It’s something like an investment fund for those who don’t want to handle the operation of their own watch hoard; Lamdin’s staff store some of the watches and suggest new purchases or trades. They also help museums acquire watches for their exhibits and assist companies in tracking down their own watches for a heritage department or archive. Many makers haven’t chronicled their own history, and they don’t know how to sift through a network of collectors to locate a single item that’s been largely lost to the ages.

Analog/Shift had about $275,000 in revenue its first year. Lamdin now puts that figure in the “many millions,” though he declines to share an exact number, and he’ll sell about 1,000 watches this year. “Are vintage watches as a category a bubble? Absolutely not,” he says. “I’ve literally bet everything I have on that.”

He’s far from alone in this gamble; Analog/Shift is part of a trend that began in the early 2000s. Chrono24 GmbH is an international platform that boasts more than 10,000 dealers and private sellers and a catalog of more than 300,000 watches. Watchfinder & Co., based in the U.K., helps you do exactly what its name implies. It was purchased in June by Richemont, parent of Cartier, IWC Schaffhausen, Baume & Mercier, and Officine Panerai. Govberg Jewelers is an almost century-old family-owned shop that’s reinvented itself to offer vintage watches, modernizing itself with an app that helps owners manage their portfolios.

Crown & Caliber LLC, an online seller based in Atlanta, recently notched its 20,000th transaction. Like many who got into the business, founder Hamilton Powell, a former finance executive, was intrigued by a string of horror stories from watch buyers and sellers—everything from a scam involving a Nigerian prince to an invitation to meet in a parking lot. He started the business in 2013 in an attempt to serve a plagued market.

“This was, in many ways, the last great industry that did not have a robust and professional secondary market,” says Powell, pointing to used cars, used furniture, and even used golf clubs. “Why did this huge market not have an easy way to transact?”

Concerns about fake or counterfeit watches remain prevalent among collectors, just as in wine and art, and for good reason. The Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry dealt with more than 2,500 cases in 2017, ranging from seized mail to warehouse raids. When authorities in Brazil inspected two shopping centers in São Paulo in September 2017, they found more than 70,000 fake Swiss watches. The group said it was involved in the confiscation of almost 2 million counterfeit timepieces last year. More reliable sellers counteract this trend.

But even working with legitimate timepieces is a risky business. There’s no such thing as a fixed margin when reselling watches, and corrections within market segments happen constantly as trends vacillate. One day a certain watch is in, the next it isn’t. For a period of years, a certain size will be popular, or a certain type of metal. Lamdin says he’s taken plenty of hits. Disappointing sales are most publicly seen at the auction house, with embarrassing results. “There are always surprises, and there are always duds,” Wind says.

But even as watches have morphed from timekeeping essentials to luxury curios, their popularity in recent years has only increased. And chasing the trends can become an addictive game.

“We have seen watches go from small to big to medium-size, from steel to gold to platinum back to steel,” Bacs says. “These are trends that are driven by greater society. We see these things and say, ‘Actually, that’s cool. I want one too.’ ”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Gaddy at jgaddy@bloomberg.net, Chris Rovzar

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.