The ‘Savings Glut’ Is Really a Dearth of Investment

The ‘Savings Glut’ Is Really a Dearth of Investment

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The interest rate is simply the price of money. And the price of money, like any price, is determined by the balance of supply and demand. So why has the price of money—measured by inflation-adjusted interest rates—fallen so steeply over the past few decades?

In principle, the rate decline has to have one of two explanations: too much supply of money from savers or too little demand for money from investors. (Or, of course, some of each.) In 2005, Ben Bernanke, then chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, focused on the supply side when he attributed falling rates to a “savings glut.” But there’s increasing evidence that the bigger culprit is too little demand. That is, a dearth of investment.

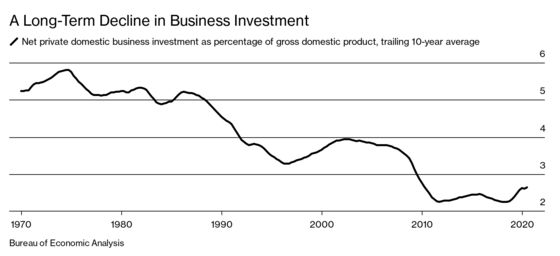

This chart I built using data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis tells the story neatly. It shows net investment in equipment, software, structures, and so on (net meaning new investments minus the depreciation of old investments) for private, domestic businesses as a percentage of gross domestic product. To quiet the noise in the data, I graphed it as a 10-year moving average; the latest data point is the average since late 2010.

British economist Andrew Smithers is one of the people who’s been arguing that underinvestment is the real problem. In Productivity and the Bonus Culture, published last year titled, he maintains that the way executives get paid is causing them to be shortsighted, paying out profits through dividends and share buybacks rather than plowing money back into the business for long-term growth.

Smithers, the founder of Smithers & Co., headed the asset management business of S.G. Warburg & Co., now owned by fund giant BlackRock Inc. In an essay derived from his book in the summer 2020 issue of American Affairs, Smithers writes, “Weak growth is far and away the most important economic problem facing the United States. This problem is not simply the result of the financial crisis or the severe recession that followed.” It began before that, he says. The cause was “a reduction in business investment.”

Smithers warmed to his favorite topic again in the journal’s winter 2020 issue, in a review of Stephanie Kelton’s book The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy. He agrees with Kelton that “savings glut” is a weird way to describe a world in which, as Kelton points out, “the typical working American has no money put away for retirement.” To say there’s too much saving is “defeatist,” Smithers writes, in that it “treats weak growth as the result of inevitable secular decline.”

In fact, there are plenty of things to invest in. Elon Musk seems to think so, anyway, and he’s not doing badly. The man behind Tesla and SpaceX has vaulted to No. 2 in the world in wealth with a net worth of a little more than $150 billion, according to Bloomberg. (Jeff Bezos of Amazon.com at No. 1 is another prodigious spender on growth.)

Smithers lauds Kelton for wanting to spark growth but writes that “the bonus culture” stands in the way. “Unless it is addressed, programs such as Kelton’s are unlikely to succeed,” he says.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.